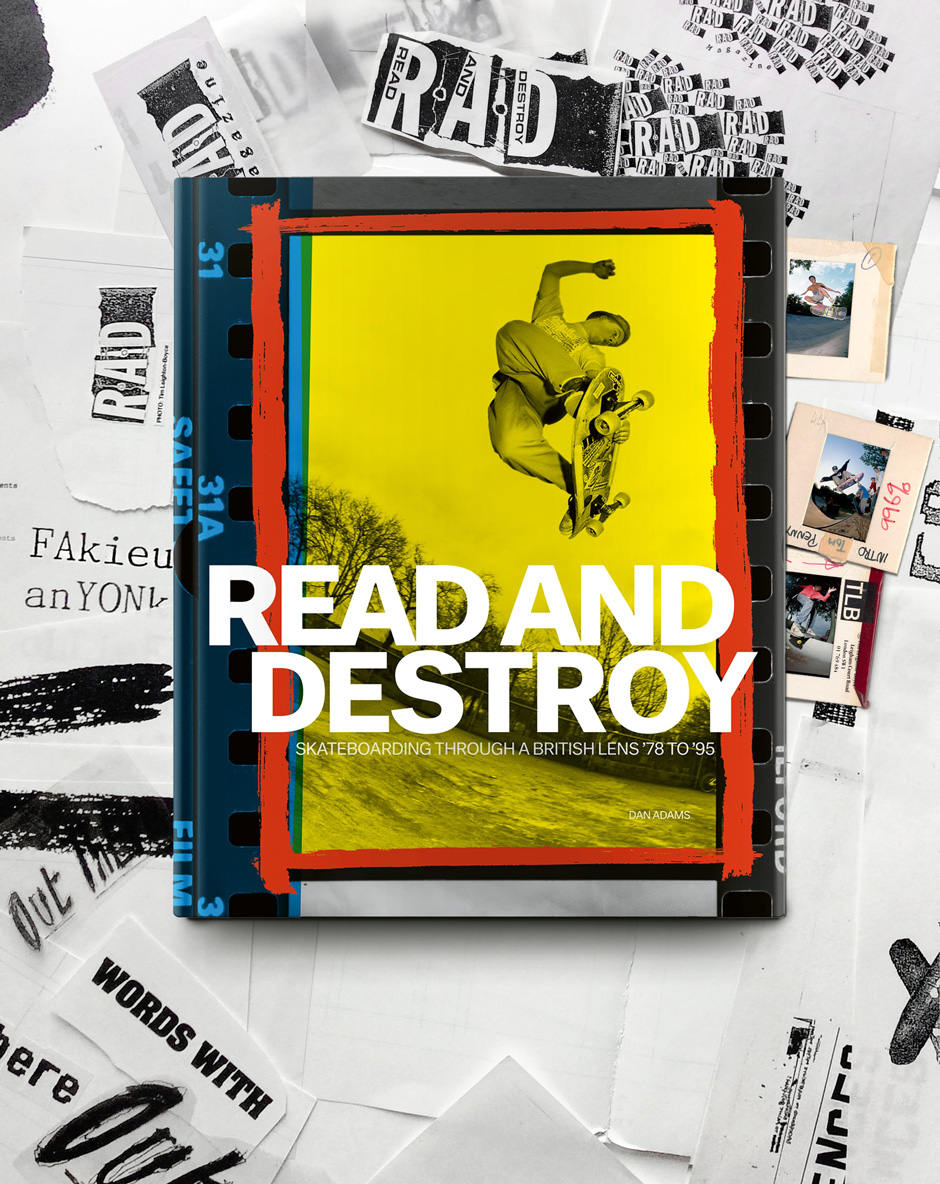

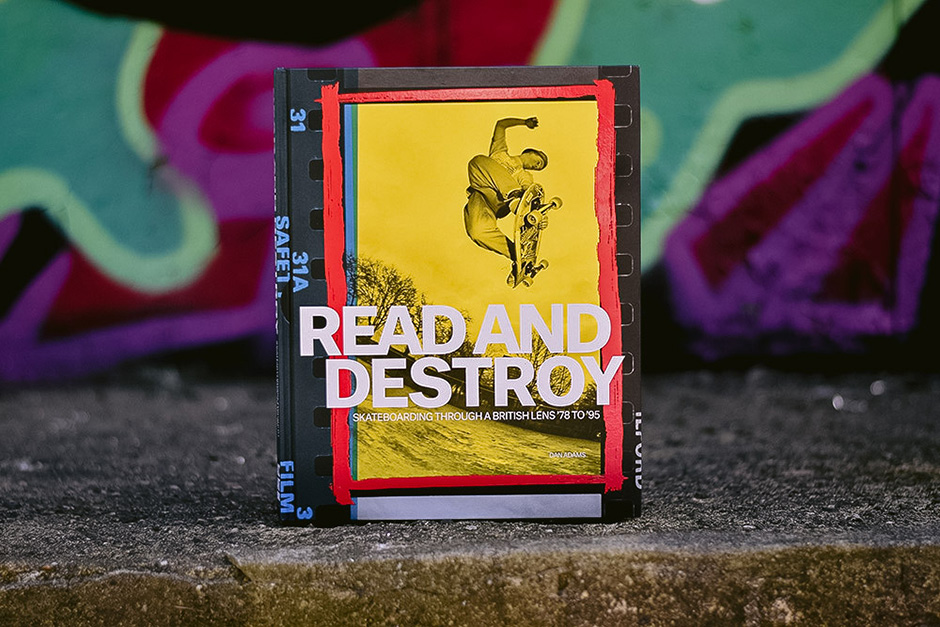

This interview with Dan Adams explores the process behind making the incredible new Read and Destroy book a reality. This celebration of RAD magazine has been years in the making, and it’s Dan’s hard work as an archivist that has made it possible. Find out more about this epic undertaking and learn about an important piece of British skateboarding history that demands a space on your bookshelf…

READ AND DESTROY – A 272 page review of the life and legacy of RAD magazine and its instigators

Dan Adams has had deep ties to Slam City Skates since its inception, a relationship that is expanded on in this interview. Over the years he has been a welcome visitor, a guide of sorts, as well as being a reliable source of information, and inspiration. He is someone we’re proud to call a friend, and we have enjoyed every opportunity to collaborate with him that has arisen over the years. Knowing just how much time and work he has dedicated to making the new Read and Destroy book a tangible thing meant we naturally wanted to devote space to telling the story of that journey from Dan’s perspective. His Shawshank-esque expedition through decades of images and ephemera to seeing the light of the narrative emerge on the other side is a great accomplishment. It was a pleasure to find out more about what went into making this gift to our culture.

We learned about Dan’s time working alongside Tim Leighton-Boyce as designer of RAD, a formative experience with its own set of challenges that underpins his emotional attachment to this project. It is Dan’s commitment to making sure the voices and contributions to the magazine aren’t forgotten that has remained a driving force throughout. The development of the archive itself is fully explored, an immense task Dan wanted to take stock of before even beginning to tell the tale. We also spoke about the lens he chose through which to approach the editing process, one focused on telling the story of the British photographers who made the mag what it was, and presenting their work in the best way possible. This interview presents the scope of Dan’s task, his reasons for the decisions he made to make sense of everything, and finds out more about the elements of the magazine, and the process of making this book, that he enjoyed the most.

By no means did our conversation find Dan basking in the glory of the book coming to fruition. When we spoke he was submerged in the process of turning the archive he knows so well into a gallery show for RAD magazine fans eager to see what has been lurking in those boxes. Once again he’s translating that material into another package that spans rooms instead of pages. We can’t wait to see this next piece of the puzzle on Thursday 11th July. Full details of the London Calling events geared around the Read and Destroy archives close out this article. We hope you enjoy learning about this epic new book, are inspired to add one to your library, and come and join us for the festivities ahead which have been designed to celebrate the life and legacy of RAD magazine and its instigators…

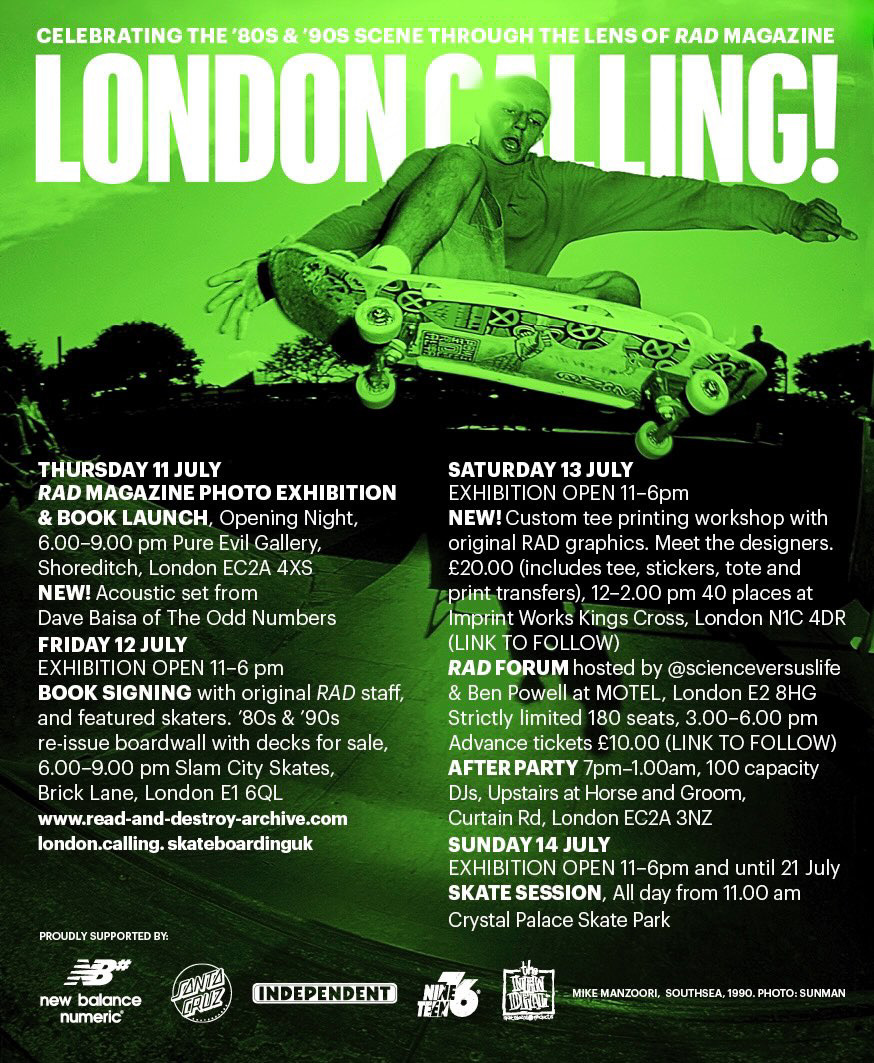

Words and interview by Jacob Sawyer. Read and Destroy book creator Dan Adams laying back on the Lotts Road vert Ramp in Chelsea back in 1988. This was shot by Slam City SKates founder Paul Sunman

Congratulations on the book becoming a tangible thing. Is it cathartic to hold it in your hands right now?

Thank you. It’s very good to see something concrete come out of all the work that’s gone on over the last few years. It’s always been a bit embarrassing to me that it’s taken so long to pull it all together. It’s good to see this stuff in print again. It was always my desire to get these photographs and a record of that time in British skateboarding history in print, which is where I have always felt it looks best. As much as I enjoy things like Instagram I still love a printed skate photo. It’s a funny thing with a book like this because when you’ve got a large amount of photography, and you’re trying to tell lots of stories that span a long period of time, it’s almost a book that could never end. But you have to draw a line underneath it somewhere just to start the story off. It’s a catharsis of sorts just to get it out there—it’s a relief.

Can you explain for the readers your ties with Slam City Skates…

I’ve known the founder of Slam City Skates, Paul [Sunman], pretty much since he came down to London in the early ’80s. He came down here to study initially, and because we were all a part of this tiny little London scene we very quickly got to know each other. Paul was a keen photographer before he was a Slam City Skates founder so we would always be around at the same venues, the same contests, the same sessions. He would always be there with his camera, or his freestyle board, and we were all just part of it. I suppose that once he got Slam going I was a customer, I would go there for my Thrasher magazines, and my Santa Cruz seconds wheels that were sold from beneath the Rough Trade counter. It all felt quite nefarious at the time, these skate products being brought from under the counter at the record store. Haha! The first people who ever worked at Slam were all mutual friends so it became part of the scene, and part of the life of the culture at the time. It still is from what I can see, it’s a very active part of London skate life.

“We all desperately wanted a colour skate mag in the UK at the time—everyone wanted a mag to represent what was going on”

In turn can you explain the role Slam played in RAD magazine’s story and what it represented for the community?

RAD grew out of what was essentially a very small, and intertwined community. initially. Predominantly it evolved from the Southbank culture of the times, you had the BMX guys mixing with the skate guys, and Southbank was where we all congregated. That’s how our network cemented itself, and how it grew, so RAD was kind of fermented in that place essentially. Paul was a very early contributor of photographs to the magazine for obvious reasons, we were all so close to it and he was eager to support it. We all desperately wanted a colour skate mag in the UK at the time—everyone wanted a mag to represent what was going on. So when one appeared, and you trusted the people making it, you were going to support them because it was good for the culture. Once Paul had a business that allowed him to spend a little bit of money, he was able to support the magazine with advertising as well. So it became this holistic endeavour essentially where it was mutually beneficial to everybody.

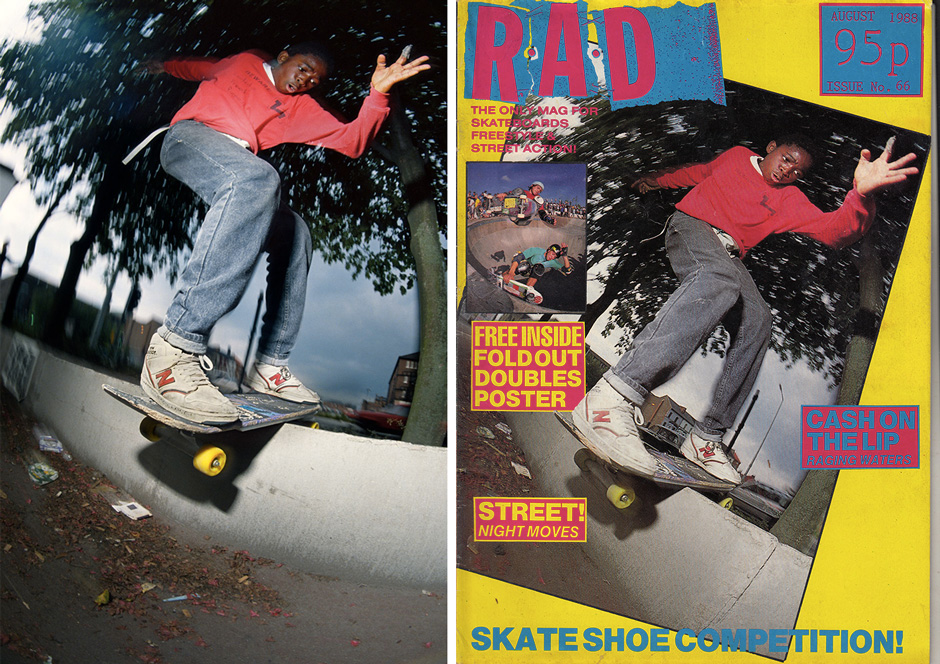

Mark Gonzales shot by Paul Sunman in 1987. This was taken one year after Slam opened beneath Rough Trade and the year the first copy of RAD magazine hit the shelves

You were a designer for RAD in the early 90s, how did that come about, is there anything you are proud of achieving during that tenure?

I guess it came about through connectivity really. I had known Tim [Leighton-Boyce] for many years, as we all did in that small skate world we all existed in. I had always been desperate to do a magazine of some sort about skateboarding. At that point I absolutely worshipped skate magazines, particularly TransWorld SKATEboarding. I had grown up feasting my eyes on Skateboarder magazine which I would probably say is the reason I wanted to do all of this. It certainly cemented my deep love of skateboarding photography. So when Ian Roxburgh had to leave the job at RAD that he’d been doing so well for a good couple of years, an opportunity arose to take this thing on. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time, and was able to step in and take over that role.

It was a tricky time because at that point the magazine had just been sold by one publishing company to another, and it was incredibly under-resourced. It was actually very difficult to put the magazine together, we didn’t even have a proper office at that time. Tim no longer had the kind of budgets that he’d had available to pay contributors in the years previous. We didn’t really have any real production facilities of our own either so we had this crazy situation where I was designing the thing using photocopies that were all cut up and spliced together on a cutting board. I would then fax those layouts down to a company that worked for the publisher somehere down in the West Country. They were typesetting those designs up on early Apple computers and generating the print files. It was a very unsatisfactory way of trying to put together a magazine.

“What has made me proud is to find out latterly how much that magazine in all its forms has meant to the people that used to buy it and read it”

Like digitising a zine…

It was like digitising a zine but using the filter of somebody else’s eye. You’re not even putting your wonderfully scrappy, exciting layout on a photocopier, and putting that out there. You’ve got some guy who is cleaning it all up at the other end. We had very short deadlines so there wasn’t much opportunity to correct things we weren’t happy with. It was quite a testing process because I had essentially two weeks to put together a whole magazine. I loved doing it though, I loved being able to finally do what I had wished I could do. I was a rookie designer at that point, I had just graduated from art college so it was an amazing opportunity. Unfortunately that experience was cut short by that publishing company selling it again just a year later. The new publishers were insistent that they use one of their own in-house people to design it. It was a challenging time for all concerned I think. In terms of my whole life’s design output it’s not my proudest moment. What has made me proud is to find out latterly how much that magazine in all its forms has meant to the people that used to buy it and read it. The fact that we were communicating something that was such a strong experience for them has made all of those past frustrations evaporate because I realised that it didn’t really matter. It absolutely did its job.

Jim Thiebaud on the cover in 1991, a Dan Adams cover decision during his time at the mag. PH: Luke Ogden

Do any covers stand out?

I was proud of being able to get that Jim Thiebaud shot on the cover, it was one I felt pretty good about. I had spent a really wonderful summer with him, Ron Allen and Jeff Klindt in San Francisco knocking around the skate spots there. Jim was just starting REAL with Tommy [Guerrero] at that time and he found out I had started this job, and sent over this package which was essentially a way of him promoting REAL over here. It was really great to have the opportunity to do that—there was also a subliminal political message in there because he’s skating the “Hanging Klansman” board. When I saw that I knew it had to be on the cover. That was a proud, subliminal, political moment.

How was it working with Tim Leighton-Boyce at that point, what did you learn from your time together?

That’s a good question, and not something I have ever really thought about, it taught me about hard work for one. I think I have a pretty good work ethic but Tim’s work ethic at that time was insane, he was doing so much to make that magazine come together. He would be out all day driving around, shooting, then coming back at night to type everything up. There would be trips in the middle of the night to processing labs to get the pictures done, then we would have to run off to Waterloo station at 3 in the morning to make the Parcelforce delivery so we hit the deadline for the photos to be scanned at the repro place in the West Country. It was an immense amount of work in a very condensed period of time to get the magazine out. That was all really down to Tim’s extraordinary input. The value of the hard work ethic is perhaps what I took away with me from the whole experience.

An iconic photo of Curtis McCann at Meanwhile 2 next to his portrait. Photos shot in 1991 and 1992 respectively by Tim Leighton-Boyce

The book does a great job of celebrating Tim’s approach, the anti-gatekeeper, community building spirit that gave readers such a strong connection to the mag.

From all of the research that went into us getting all of the material together, and then trying to unravel it, that was the thing that became the most common thread. It was something that anyone I spoke to along the way, all celebrate. They all said that Tim was this amazing facilitator because he was open-minded, and non-didactic about his working relationships with people. He was willing to let them flow freely because he trusted their creative minds, and respected them. Professionally I have never worked with many people like that, and the immense value of that approach became apparent. It’s a mindset that’s really intrinsic to skateboarding which is something that has free-flowed its way forward with such incredible progression. Because of this non-didactic nature it has allowed itself to go where it wants to go by trusting the creative talents doing it. You can go out there and change the game, there’s never going to be a kind of coach or patriarch figure who is going to say “sorry you can’t introduce that trick into the pantheon, it’s not legit”. Ultimately it’s about the spirit of skateboarding.

For someone reading who has grown up in a digital age it also communicates just how much of a channel it was. It provided a real connection to skateboarding in the UK, but also via Steve [Douglas]’s updates it was a source for the most current news from the US.

I’m glad that’s coming through from the book. It was another major, recurring thread. People would say that it’s impossible to communicate just how important the mag was to their life. It’s so easy to forget just how limited information was back then. When I stop to think about it I can remember very clearly how limited it was. It is worth emphasising that, because we are all flooded with so much information nowadays that none of us can keep up any more. So to have this very selective, single document, that can have so much meaning, was quite a powerful position to be in really, a powerful voice. I don’t think that voice was abused, it was used in a very democratic, and on the whole, a very objective way. That was Tim’s way, not to be dictatorial, or to force any idea of his own across. He wanted to bring in other voices and to make sure they were all being heard.

“I value those times, I value those people, and I really value their contributions to skateboarding. It’s always been important for me that those voices and contributions are not forgotten”

Whose idea was it to make a book in the first place? When did the idea germinate?

It formulated a very long time ago, and actually, the first meeting we had about it was in the Slam offices. That would have been around the time that Dogtown and Z-Boys came out [2001], something which made us all take stock of the stories and photos of our own. We realised that all of the photographers who had worked on the magazine had all of this material parked, and hidden away. We all thought it would be great to get this stuff out there, and had several conversations about it back then. There were a few false starts along the way, different people came and went. But the germ of the idea remained in my head as an important thing to persist with. I value those times, I value those people, and I really value their contributions to skateboarding. It’s always been important for me that those voices and contributions are not forgotten.

Femi Bukanola boardsliding in Manchester for Tim Leighton-Boyce’s lens. An altentaive shot ran as the cover of RAD Magazine in August 1988

Let’s talk about the process of getting to this point. When did making sense of the archives properly begin, where are they drawn from?

Obviously setting aside time to undertake archiving projects or even just editing projects is a costly thing. You need to be able to donate your time. That’s something that has always slowed it down, not enough people, with not enough time to donate freely. The fact that Seb Palmer from New Balance had offered some money to get the project kickstarted again was really what enabled it. That meant you could put down tools on another job and commit some time to the project properly.

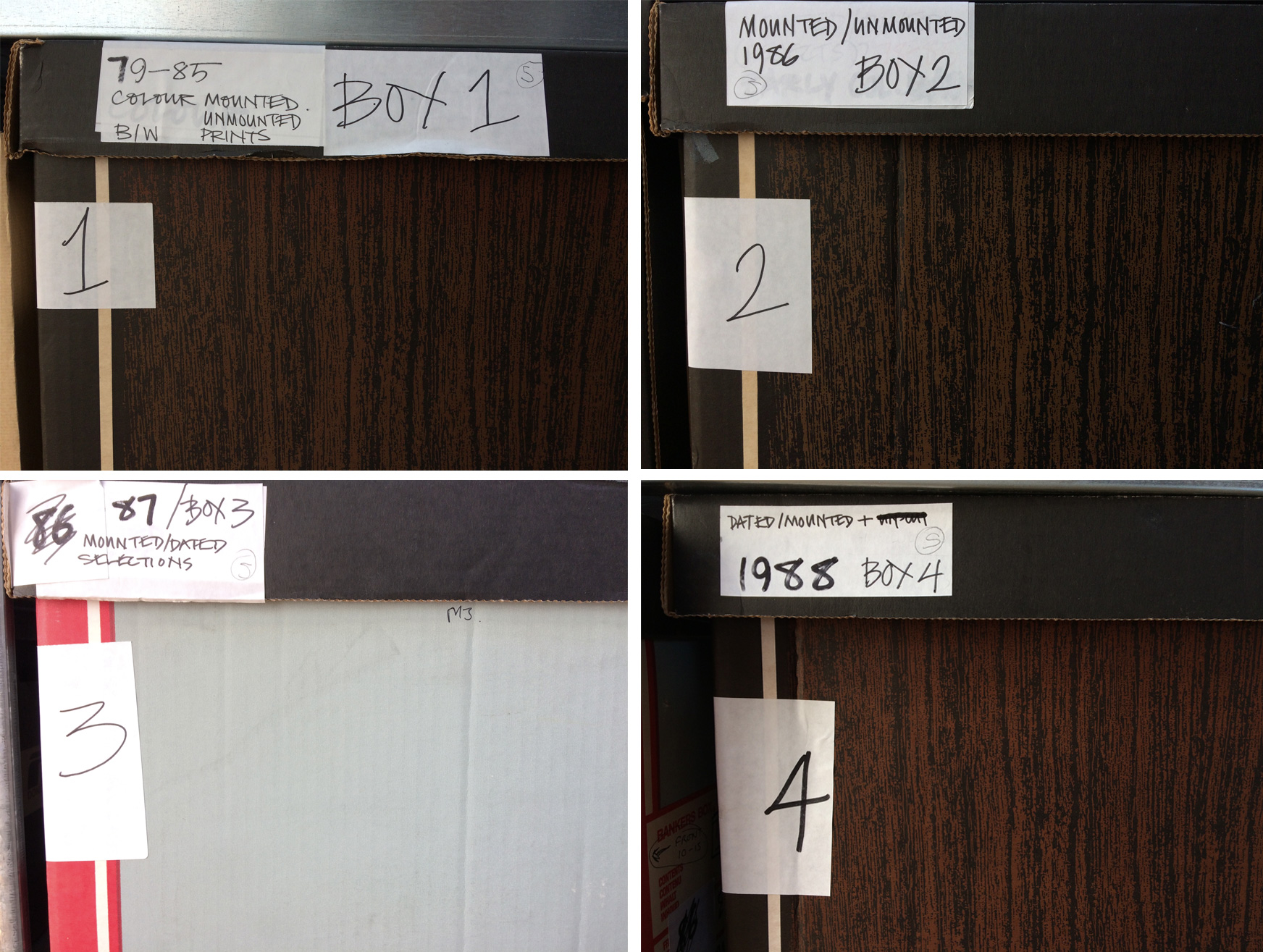

It involved going to a lockup that Tim Leighton-Boyce had, just to keep everything out of the way principally, and sifting through these boxes that were in a pretty parlous state really. There were probably about thirty large archive boxes, alongside various other assorted envelopes, folders, and files. There was quite a heap of stuff from Tim, then all the other photographers had their own boxes of different shapes, and sizes hidden away. It started out with this immense sifting process in order to make sense of what was available to look at. Were we dealing with all the bangers, or were there whole boxes of outtakes? That was stage one which took a long time. I felt that if I were to do these vast archives justice I needed to know that I had seen it all, I needed to know the entirety of the material. Even if I couldn’t physically use all of it, I had to have a sense of what constitutes the archive. If five photographers had come to me with forty photographs each, already scanned, we could have sat down and done a book quite quickly. This has been a very different sort of project though, the bulk of which has been the development of the archive itself.

“I felt that if I were to do these vast archives justice I needed to know that I had seen it all. I needed to know the entirety of the material even if I couldn’t physically use all of it”

You have Tim’s complete archive, how does he feel about these photos today?

He has always been quite non-committal about it actually. His approach with the photographs, and the magazine, was always quite hands-off. He was always ready for other people to make the choices and respected other people’s reasons for making those choices. He didn’t tend to interfere with the art directors, designers, picture editors, or whoever may have been going through those photos. That approach sustains today, he is very much hands-off and is often pleasantly surprised when I pull something out. He’ll say “Did I take that? I like that”. I think to a degree he’s probably parked the whole experience, it’s a chapter in his life which he hasn’t needed to revisit particularly. I think it’s kind of good that other people can go through these things because they’re able to be objective.

Every photo included has involved a huge amount of work from yourself. You have been digitising slides but also meticulously retouching photos. Did that process get any quicker and do you find it enjoyable?

It has got quicker but it is definitely a laborious process and a costly one. Scanning analogue photographic material is a long process, there is quite a lot of debate about the best methods. Wig Worland and I have discussed many different methods, and tried out many different approaches to land on one we felt was cost-effective and reasonably quick. It’s something I have come to enjoy actually, you get to really engage with the photography up close. Obviously cleaning off lots of dust, and bits of beard hair in Photoshop can be a bit tedious. But to bring an image to life and make it really ping is good. Even to recover images that might not have made the grade back in the day, modern Photoshop methods can work to really boost things.

Some RAw RAD material. Folders and files had to be made sense of before scanning could begin

Can you think of any images your work transformed from something once lost or discarded to something usable?

That applies mostly to photos in the very early section of the book taken in the ’70s. Tim had been shooting back then for Skateboard magazine but only for a couple of issues before it went out of business. So he had rolls of film that had never really been seen by anyone. They were right at the bottom of all of the boxes. Maybe the odd two had snuck out of there and made it into the pages of RAD when they were doing history pieces or reviews of the old days. Not many of them had ever been used though. Those photos were the most exciting because they seemed to be the most rarified, the most unseen. With most of the other stuff there are outtakes, and alternatives but the general setup, the people involved in the pictures, and the places, will have been seen before. When it came to the ’70s ones they were much more enigmatic for me which is why I had to include them in the book. I felt that Tim had these very vivid photographs from an earlier time that nobody knew about which predated RAD but were the reason that he ended up doing a skateboard magazine. That seemed like an intrinsic part of the story if you were going to tell it.

“Tim had these very vivid photographs from an earlier time that nobody knew about which predated RAD but were the reason that he ended up doing a skateboard magazine”

Early shot from the TLB archives. This photo of Derek “Jingles” Jhingoree shot at Rolling Thunder in 1979 has never looked better

It’s a book representing the archives and that’s ultimately where they begin.

That’s what I think. I’m sure there are going to be people out there who will say this isn’t a book about RAD, it’s a book about something else. I think it is in the sense that the story [of RAD] has a beginning, a middle, and an end. In a way RAD magazine is the end, and TLB is the middle. But he came from somewhere, he has a legacy, skateboarding has a legacy, and I know something about that because I was there. There are people who picked up RAD when they were twelve or thirteen in the late ’80s who won’t know anything about that era before. I think skateboarding is much more open to these wider stories nowadays than perhaps it used to be. I also think older skateboarders are more open to historical backgrounds so I felt like it was the right time to bring all that to the fore.

What is the untapped reality of the archives as a whole. Could you come up with a ballpark figure when it comes to images?

Bloody hell, the physical number of images? I’m not sure I could begin to think about that. There are probably 25 binders of black & white negatives covering fifteen years. Thirty boxes of colour photography of one sort or another. I can’t even begin to calculate but it’s certainly the biggest archive of skateboarding photography from that period, and perhaps from any period. Bar the digital photographers who are able to accumulate tens of thousands of images without even thinking about it. As far as physical archives of skateboard photography, it’s got to be the biggest one in the country, thousands of images. Combine that with the work of Paul [Sunman], Jay Podesta, Mike John, and others, you’re adding even more to the mix. It was no mean feat trying to find a path through it I have to say, it was a little bit intimidating. Tim’s career as a skate photographer stopped in the early 90s but I suppose there are photographers who picked up where he left off who transitioned from film to digital. There must be some other big archives out there for sure.

The archives run deep as the Mike Manzoori files attest. “Mostly Manzoori” would be a great name for a band

The book as a project from the original vision has existed in different formats, beginning with a vaster page count. Was it difficult having to be ruthless in terms of editing everything down?

At one point there was a project to make two volumes in one package when I couldn’t see my way through the sheer amount of material that there was. I was made aware, by the publisher of the weight (of the project) that puts on you. At each stage they would say that you could do a book that’s 400 pages but you could also make a smaller one and make further volumes later on if there’s the appetite for it. So it became time to get ruthless which wasn’t always easy, editing is difficult but not impossible. In some ways it’s quite good to be ruthless sometimes. I’m aware with these things that there’s a subjective element to it, some people will have their favourites, and ask why something was chosen over something else. I think it’s about the overall effect that it conjures up, for me it was about trying to capture the spirit of those times, and the people who made those times interesting.

“for me it was about trying to capture the spirit of those times, and the people who made those times interesting”

Alex Moul’s input was definitive. This Willy grind in Harrow ran as a poster in 1991. PH: Tim Leighton-Boyce

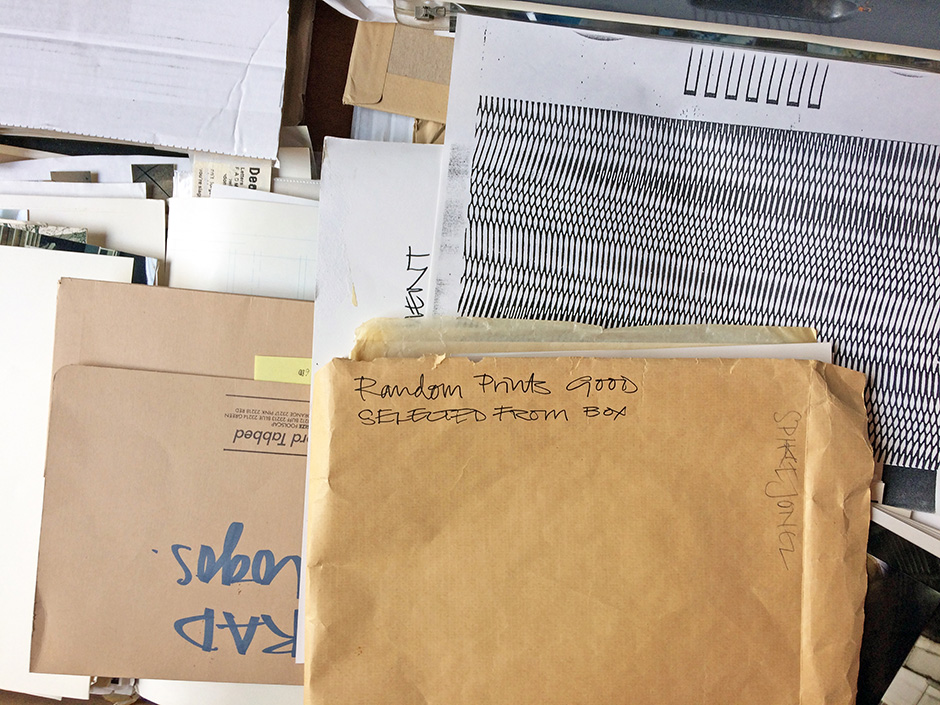

Has spending a lot of time looking at Nick Phillips’ anarchic visuals left you with a hankering for less polished, more chaotic aesthetics when it comes to layout design? How has that informed your own eye/ taste for how things should look?

It’s funny you should say that. While searching around for a solution to the cover which is obviously a very important thing for a book I began by playing with a lot of tight-arsed typographic solutions. I did think then, ‘I need to be more Nick here’, I need to channel my inner Anarchic Adjustment. That’s why I began blowing up the contact sheets, and using the markers that had been used on images to pick out the best shot. Making something a bit more rough and energetic, then infusing it with the fluoro colours Nick was always so fond of. I think those were very much the spirit of the magazine, a sense that your hand had been used to create the work rather than a machine. That was the spirit of the mag which came from the spirit of making Zines before that.

“It was always an objective of mine to frame Nick [Phillip], Ian [Roxburgh], and Steve Hicks’ work in a way that shows it off the best and to give it context. And also to let the photographs be seen without any graphic interference”

What I didn’t want to do in the book itself is try to imitate that kind of approach inside because I think that can sometimes look really corny. One publisher I spoke to asked if I could make it look more “skateboardy” based on the some idea that it’s this anarchic pursuit. It was always an objective of mine to frame Nick [Phillip], Ian [Roxburgh], and Steve Hicks’ work in a way that shows it off the best and to give it context. And also to let the photographs be seen without any graphic interference. Obviously in the magazine they were always behind something, or graphic elements surrounding them or cutting into them. That was exciting and right for the time but I wanted to find a more timeless solution for displaying these things.

It would be counter-intuitive to spend hours retouching something before overlaying anything once again.

In a way yes, I didn’t really think about that but you’re right. It’s been good to reminded how we’re all very much tied to these machines and these software packages that we all use to design things. In the absence of a strong creative mind or with a fast deadline in the way you allow the machines to take over I think. Nick was very much allowing his personality to take over with his work, different times and processes it was interesting to revisit.

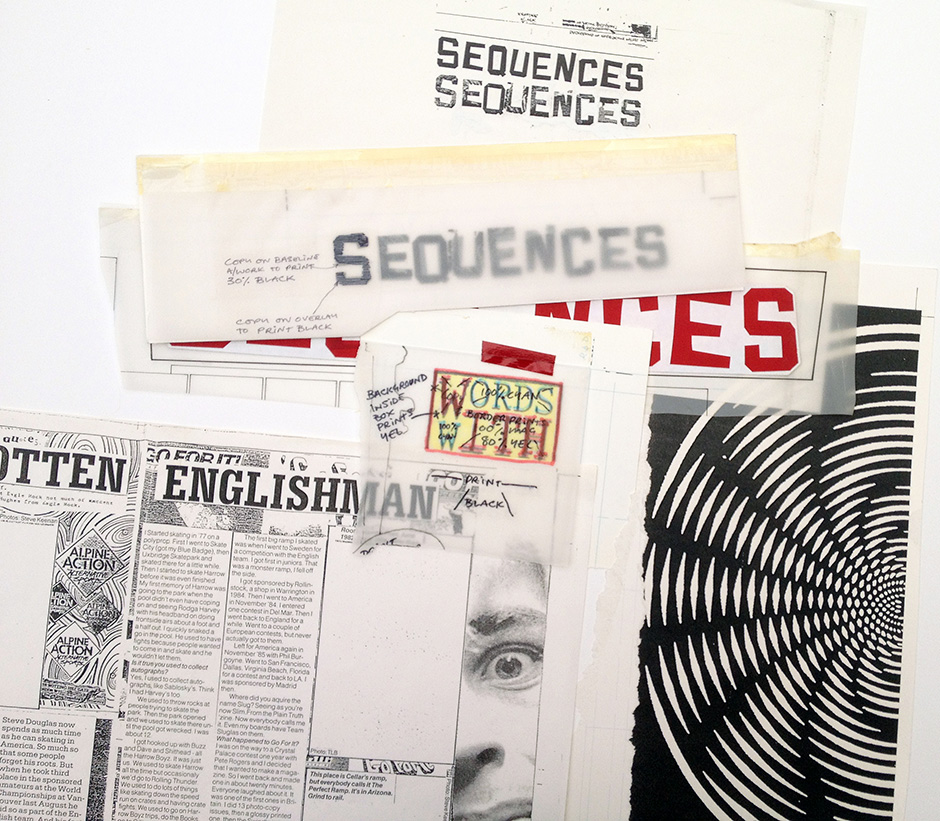

Some of the ingredients that went into a Nick Phillip layout

I like how you have still incorporated that aesthetic though, involving ephemera and text in the layout.

It would have been great to have more opportunity to do that but I’m glad you think it’s worked. I always wanted this to be a celebration of the photography first and foremost. The graphics were always a way to present the photography. It had to be in there because it was a vital part of the magazine people really responded to. It was important to remind people of how vibrant it had been. With more space, and a bigger book there would have been more opportunity to include more of that. I wanted to try and give a sense of what it has been like for me digging through all of those boxes. Looking at contact sheets, and actual pictures, showing the sprocket holes on the film stock, and that kind of thing. Giving a glimpse of that analogue material and what it actually looks like when you’ve got it in your hand or on a lightbox. I felt that was an important thing to display, to give some sense of being involved in the archive itself.

And what it was like to create the magazine to begin with.

Yeah exactly, that’s a very good point. Those are all of the ingredients on your desk when you’re putting a layout together. There’s a lightbox next to you, slides are strewn about all over the place despite the fact that they’re these wonderfully fragile little things. They were treated with quite a lot of contempt really. There are letters from readers included in the book showing you what kind of stuff came through in the mail bag. Little glimpses into the process.

You must have interviewed a lot of people for this. Was that a big task in itself?

Quite a lot of people, principally the main people involved in the making of the magazine. It would have been interesting to talk to more people who were around the periphery of it. There were some people who were essentially fans at the time who I spoke to who gave wonderful insights. Someone like James Davis in particular who expressed incredibly eloquently how he had engaged with the magazine and what it really meant to him, reflecting on the famous “Southrop Affair” article which appeared in the mag. Talking to people like that was very enlightening. Interviews are a difficult thing because you can kind of do them forever. I’m amazed at the appetite Neil Macdonald has got for following the trail. He has interviewed everyone for his book Elsewhere and the amount of information he is gleaning is just incredible. Unfortunately I don’t have quite the same appetite for that much information. I was very much focused on digesting the photography and getting the best out of that in a way. That was where my personal desire for information led me.

Did anyone’s ideas about the mag change how you looked at it? Did you learn anything you didn’t know previously?

Primarily it was just coming to understand how important it was, that was the main thing. Also finding out what an important figure Tim [Leighton-Boyce] had been for all of the people who had worked on it. That was something I had never fully understood at the time, I think they probably hadn’t fully understood it at the time either. You often come to know these things in retrospect, you realise who your mentors were, who gave you the greatest impetus in your working career. That’s not always apparent at the time. Threading all of that together and hearing it re-emphasised time and time again from different people was an important focal point from which to build the story.

Joe Millsons ramp in 1990. Tim leighton-Boyce capturing more than just tricks

Do you have any particular favourite shots? Can you think of an example of something you were blown away to see on the Lightbox?

That’s so difficult, I’m blown away by all of the photos for different reasons. The ones I am most struck by always aren’t actually the action shots. They’re photos of people’s shitty ramps, I just love those. The beauty of skateboarding for me has always been the way that you can be hidden from the view of mainstream society and build these very vibrant communities for yourself. In my day that was often focused around ramps. I know nowadays that would be a spot or a range of spots that you congregate at. The way these ramps facilitated community building was incredible. You get in there and you have to build it together, you learn on the job because you’re not a professional carpenter, you often have to acquire the materials through underhand means or by scrimping and saving. I think those ramps were amazing enablers for the culture so I’m always very touched and charmed by those photos. They’ve got a lot of longevity for me.

“I think those ramps were amazing enablers for the culture so I’m always very touched and charmed by those photos. They’ve got a lot of longevity for me”

I can obviously also happily look at banging skateboard shots all day long. I suppose the one that keeps singing out to me, and one that I keep using is the photo of Curtis [McCann] doing a melon grab out of a little kicker at Meanwhile 2. That’s on the A+ list for me but there are more, and every time I go back in there I find more. I have to say that I am a little snow-blind from it all right now. When I initially started going through the boxes I was consistently blown away that certain shots still existed at all.

You were responsible for Latimer Road vert ramp, something people flew to the UK to skate. What’s your favourite moment in RAD captured there?

I wasn’t responsible for it but I was involved in the building and making of it. It was group effort but I wasn’t an instigator by any means. I did the drawings for it and did some of the building work but by no means was I the chief architect as it were. I did the specifications and all of the drawings for it but it was built by a guy called Simon Chambers who ran the youth project down there. He was an amazing guy, a sculptor, and builder. I would call him the chief architect, I was the chief advisor/ quality control technician. There was a whole bunch of us who actually built the thing, all sorts of people came together.

Latimer Road vert ramp under construction in 1987. PH: Paul Sunman

There’s an insane shot of Mark Gonzales doing a frontside fastplant in black and white, it’s so big that it took Tim completely by surprise. He almost couldn’t get the lip in the shot because it’s so boosted. There’s also another photo of Jeff Grosso doing a frontside handplant. I’m very taken by that one because he himself said that he remembered that picture vividly, something I thought was very flattering for Tim. But it also reflected that for him the ramp had been so good, he had expressed that in relation to that photograph which made me immensely proud of being involved with the building of that ramp.

Jeff Grosso stamps his approval on the Latimer Road vert ramp with a frontside invert in 1987. PH: TLB

I know that the other American pros who visited in ’87 and ’88 were all hugely complimentary of it at the time too so that was a proud dad moment for me I suppose. It’s only slightly heartbreaking that it was in a really challenging part of the city which meant that no-one wanted to go there. Slam were a big supporter of that ramp. Paul [Sunman] intercepted that project—he caught wind that a half pipe was going to be made somewhere round there. He was adamant that if they were going to do it they had to do it right. Paul was the one who set that on the right path, then SLAM ponied up and spent money on the steel. Like RAD magazine that was a project that came out of the community, it was an inter-connected thing. That’s what makes all of these things so wonderful, the connectivity really, and how it pools people’s skills together without anyone being paid.

Every photo in here is shot by a UK photographer even if the skater is from the US so it’s all through a British lens as it were?

That’s right, that’s not to minimise the contributions to the mag from people outside of the UK, American or European. We just had to focus the choice somehow. Conversations early on landed on us celebrating the British guys because they’d never had a chance to be celebrated like that in print. So we decided to focus on those photos, and if the opportunity arises at a later date we can loop back round and catch all of the other American and European contributors in a different volume or project.

Californian manoeuvres captured through a British lens. Mike Vallely frontside boardslides in 1987 while Paul Sunman shoots

It’s great to see Paul Sunman’s photos in there and to romanticise some of his work like the Mark Gonzales Gonz gap photos which are a story by themselves.

They are, Paul has some nice stories about that, it’s all so wonderfully random. That’s the other thing about these pictures. Going back through these things you realise how special they are. How come there is only one photo of Natas [Kaupas] on a tour to the UK in ’89? Just one picture from one photographer, then you realise these things were so random. If you didn’t get the call on your house phone that someone was going to be somewhere on a certain day you wouldn’t know, and you wouldn’t be there to take the picture. Paul happened to be able to shoot Mark on that occasion because Mark turned up at the shop. He had come to London on a whim almost, without any kind of schedule. He turns up at Slam because it’s the skate shop he knows about in the UK and apparently says “come on I want to go skating”. He had to go somewhere later on but wanted to skate beforehand.

“that’s another thing I’ve been made aware of going through all this stuff, just how fleeting and serendipitous these moments were”

If you’re there and happen to have your camera it’s a serendipitous moment. If you have to go home to get the camera and he’s gone off skating or decided he doesn’t want to skate any more that moment has passed. So that’s another thing I’ve been made aware of going through all this stuff, just how fleeting and serendipitous these moments were. If you didn’t get the call you weren’t going to get the shot, maybe no-one would. Nowadays you see something on Instagram as it’s happening and get yourself across town. In some ways how did we manage to do anything without mobile phones? But we did, it worked.

We’re looking forward to for the launch of this. It’s great the Slam shop is involved for a signing the day after the gallery opens. When we did the RAD T-Shirt launch night pre-Covid it felt like a mini London Calling. It was great to have Vernon Adams, Paul, TLB, Winstan, Wig, yourself, and everyone out for the night. I hope it’s more of the same…

Thank you, we’re excited to be involved. I think it will be a continuation of that night and I’m very much looking forward to it. I’ll go back to my buzzword but it’s about connectivity, it’s taking it back to where it all began which is always very exciting for me, but with new people in control, making it contemporary and relevant as well.

A virtual leaf through the pages of the new read and Destroy book which releases on July 8th

Does setting up the photo exhibition feel less daunting after last year’s successful gallery opening?

No it’s actually more daunting because it’s a broader spectrum of imagery. It covers a greater range of different kinds of skateboarding, and I’m trying to do something slightly different to last year so it’s not just a repeat. It’s not entirely anxiety free.

There was a conversation about having a further 90s zine to accompany the book. With the vast archive to hand could you envision another volume or separate project taking shape in the future?

There won’t be a zine unfortunately, there just hasn’t been time or budget to do that which is a great shame. That’s not to say that it won’t happen in the future. There is plenty of scope there for other projects. With a big archive like that it’s possible to slice and dice it in different ways. I’d almost love someone else now to come in with their vision, and I could help facilitate them making choices. Now I know what’s there, I could guide someone else’s eye and illustrate that story in a different way. Although I’ve tried to be very objective about what’s in there I’m very aware that there’s always an element of subjectivity to all of this but I hope I’ve nailed it.

You could come at it from many different angles. You could make a book that’s entirely vert ramp photos for instance.

Totally, which I would enjoy doing very much because that’s what I grew up worshipping. Maybe now with vert skating in a slightly more ascendent place it would be a good time to do something like that. You could look at the archive through all kinds of different lenses. Tim was very good at photographing skate spots in the built environment, he always had a great eye for that. He could see a skate spot as well as any skateboarder out looking for the right ledge or obstacle. Those photos would make a great book of their own. It would honestly be amazing for each photographer to have their own volume, they all have their own strengths. It was very difficult to find space for everybody in a way that did them all justice.

Wig Worland may never have captured much behind the scenes action but he more than made up for it with skate photos. Carl Shipman frontside flip at Radlands in 1994

Do many photos of the photographers in action exist?

Weirdly not, not very much. Sometimes photographers would point the camera at each other—there’s a great photo of Mike John in full ’80s regalia, brandishing his camera, shot by Jay Podesta—but not often. With film being so expensive, and the number of frames so limited they tended not to waste it. If they were there to shoot a session that’s what they would do. One of Wig [Worland]’s great frustrations now retrospectively, is that he never shot anything other than the actual trick that was going on. Sometimes they were caught in the background if there was more than one person shooting. There’s actually a nice one shot by James Hudson of Tim on the deck totally knackered, taking a break in between sessions. It’s like he’s taking a nap on the platform and James obviously thought that was kind of funny. There’s another shot that’s not in this book that Neil Macdonald dug up from James’ archive. James took a photo of Tom Penny at Radlands and in the bottom of the frame is Tim taking a photo which is the one that was published. There are a few nice moments like that where two photographers are capturing the same action from different angles.

Last words?

From my own point of view I am extremely grateful as a skateboarder to all of the skate photographers who have made skateboarding so vivid and exciting for all of us. That has been the driving force behind me wanting to make any kind of publication of skateboarding photography. I live vicariously through their archives.

The READ AND DESTROY book goes on sale on July 8th

You are invited to celebrate the release of the new READ AND DESTROY book in person over a busy four day schedule filled with events…

This year the London Calling event is geared around this publication. We are pleased to be hosting the book signing at our East London Shop on Friday 12th July. Be sure to put these dates into your diary and come to join Dan Adams and the squad who made RAD magazine possible. You can also sign up ahead of time for the Print Workshop and ensure your place at the RAD Forum. Follow Read and Destroy and London Calling for further updates.

We would like to thank Dan for the time he took with this interview and the supporting assets he provided. We would also like to thank Neil Macdonald [Science Vs. Life] for the mag scans from his personal RAD collection. Finally we would like to thank all of the RAD photographers, designers, contributors, and readers who have all played a part in the legacy of this important magazine.

Related Reading: Neil Macdonald Interview, Alex Moul Interview, Carl Shipman Interview, First & Last: Mark Gonzales, Slam City X RAD Archive: Curtis McCann, Dressen at Southbank 1987, London Calling Event 2023, Slam City Skates – The Logo