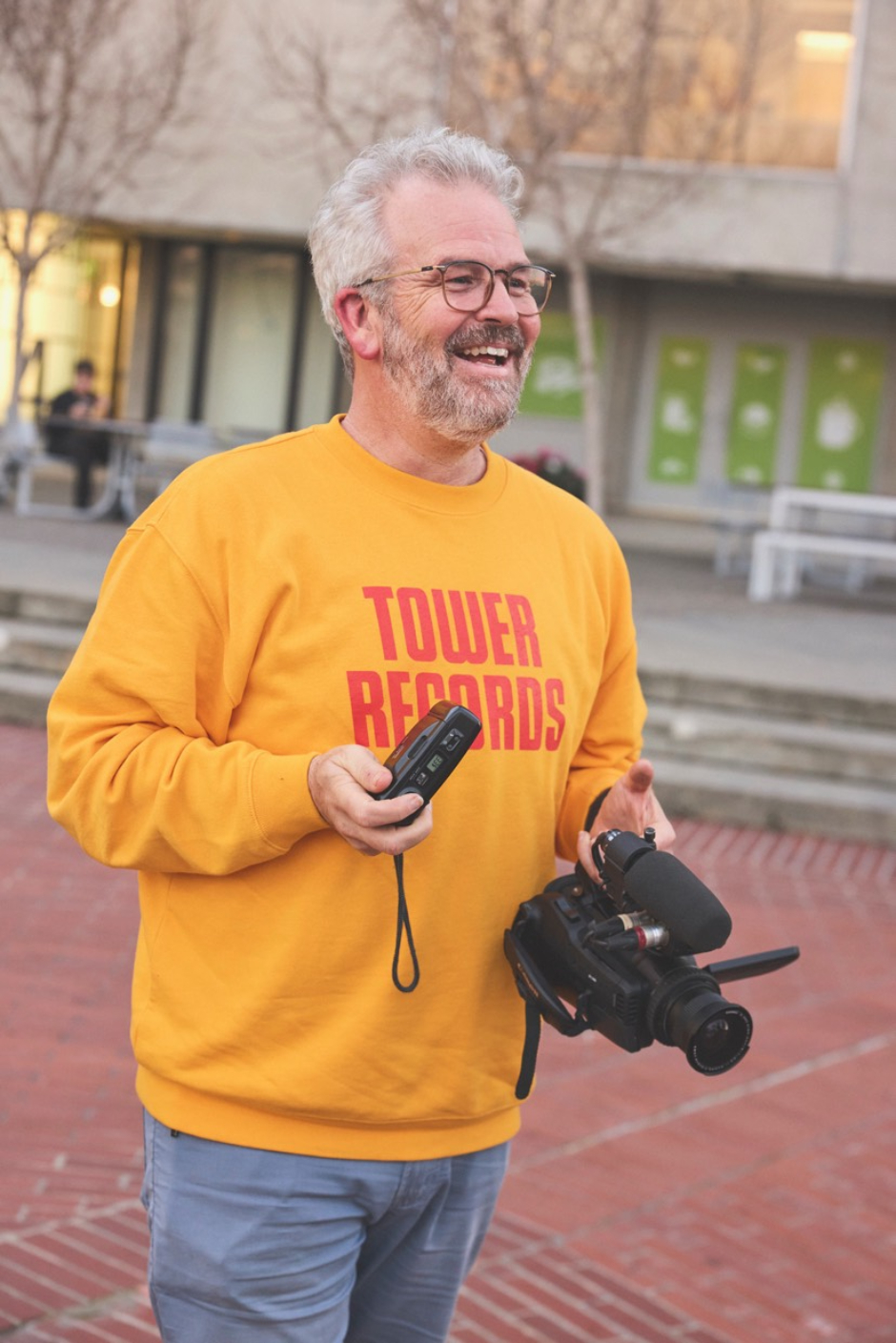

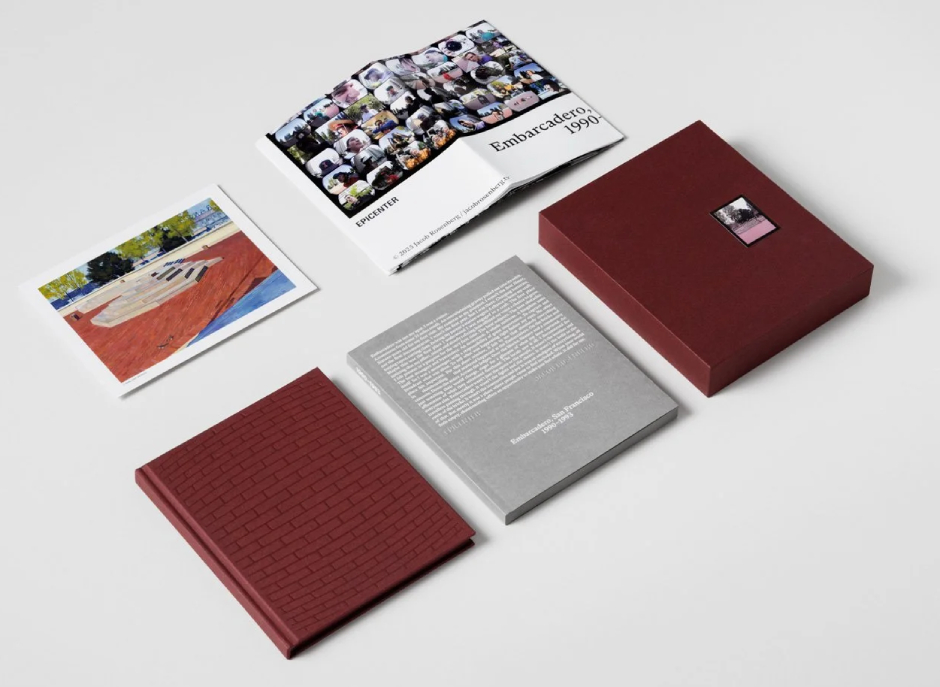

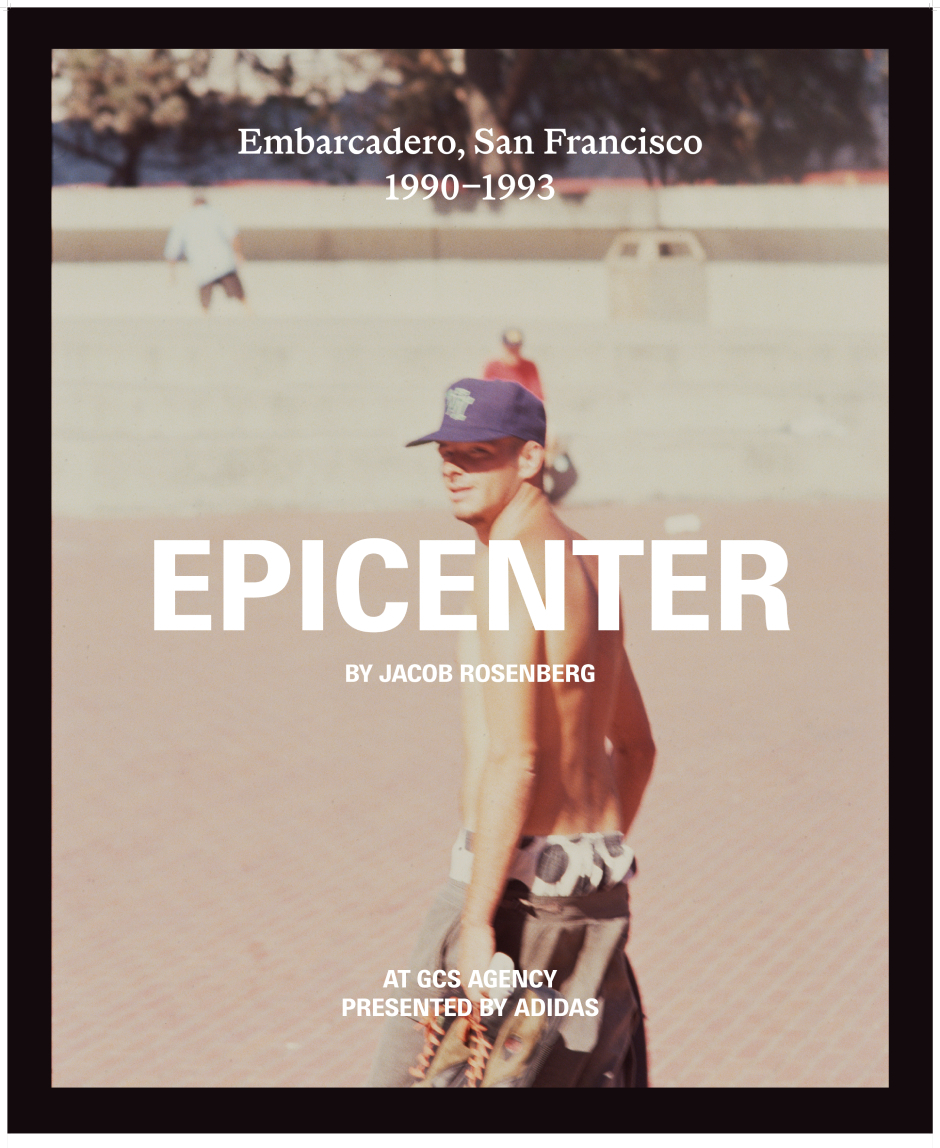

Welcome to our “Visuals” interview with Jacob Rosenberg, someone whose contributions to our culture are numerous. Following the closing of his EPICENTER exhibition, we used this format to explore some visuals that impacted him during one of his most prolific periods, before delving into his recent love letter to Embarcadero…

Words and interview by Jacob Sawyer. Jacob Rosenberg at Embarcadero. PH: Pete THompson

Jacob Rosenberg’s story is full of remarkable contributions to skateboarding culture, one that begins at skate camp, where an unfortunate broken bone ended up manifesting a revolving door of different opportunities as a filmer. From his formative experience at camp leading to a “Jake the Janitor” credit in Shackle Me Not, his path would evolve rapidly. Much of this momentum came from his proactive instinct and an innate ability to connect with everyone he encountered. Maintaining relationships with new friends met on the contest circuit developed into a trip to LA filming Guy [Mariano], and Rudy [Johnson] for bLind “Video Days”. This led to crafting full videos for Dogtown and Think and a full circle reconnection with his skate camp director Mike Ternasky who enlisted him in the Plan B program, entrusted him with capturing Mike Carroll for Questionable, and opened up a whole world that would become an incredibly significant moment in skateboarding’s evolution, with Embarcadero in San Francisco as the focal point that all eyes were trained on.

Jacob didn’t just capture footage at Embarcadero during this pivotal period of time; he captured a moment, and he kept the tape rolling. His vast archives now offer a window into a wonderful world gone by, providing a comprehensive overview of an era changing in real time. This period, spanning the beginning of the 90s through to 1993, is one Jacob has revisited and repurposed for a viewer in his incredible new book project, EPICENTER. This labour of love is an ode to the time he spent at this iconic spot, and it is the story of what transpired in front of his lens. The book brings together photographs, screengrabs, interviews, essays, and artwork. The narrative is his own story, the story of the plaza, and the story of some of the key figures who put it on the map, created with the awareness that the powers that be have other designs for its future. Knowing that this book was out, and having watched the powerful reunion the opening had prompted, we wanted to connect with Jacob to mark this moment. We agreed on a format and spoke shortly after he returned from the closing event.

With the ultimate aim of reflecting on the book project, the gallery show, and Jacob’s feelings about what was achieved, including key collaborator Ted Barrow’s dialogue about the future of the space, we chose to take a slightly different route of reminiscing before doing so. There have already been a few great interviews with Jacob about his history and this project, which are linked up after the close of this article. Not wanting to reexamine the same subject matter, we decided to look at the earlier years of this time period, but not specifically through his own lens.

This “Visuals” interview instead explores things that left a lasting imprint on his psyche, some from a seminal video that he contributed to, but approached from the perspective of a fan witnessing something transformative unfold. We talk about Rudy Johnson’s part in Video Days and the reasons why he will always be a favourite. Another moment from the same video is revisited, a fleeting whip crack of pure progression from streetskating visionary Mark Gonzales, emblematic of the ATV nature of his part. Jacob’s photo pick is a Daniel Harold Sturt and Kris Markovich banger that redefined the rules, inspiring others to look at things with fresh eyes. Finally, one of the best board graphics of all time is discussed, Jim Thiebaud’s “Hanging Klansman” REAL pro model, a powerful, uncompromising piece of imagery with no missing message. The visuals explored lead us back to the amazing EPICENTER book he has created, one that belongs on all of our shelves…

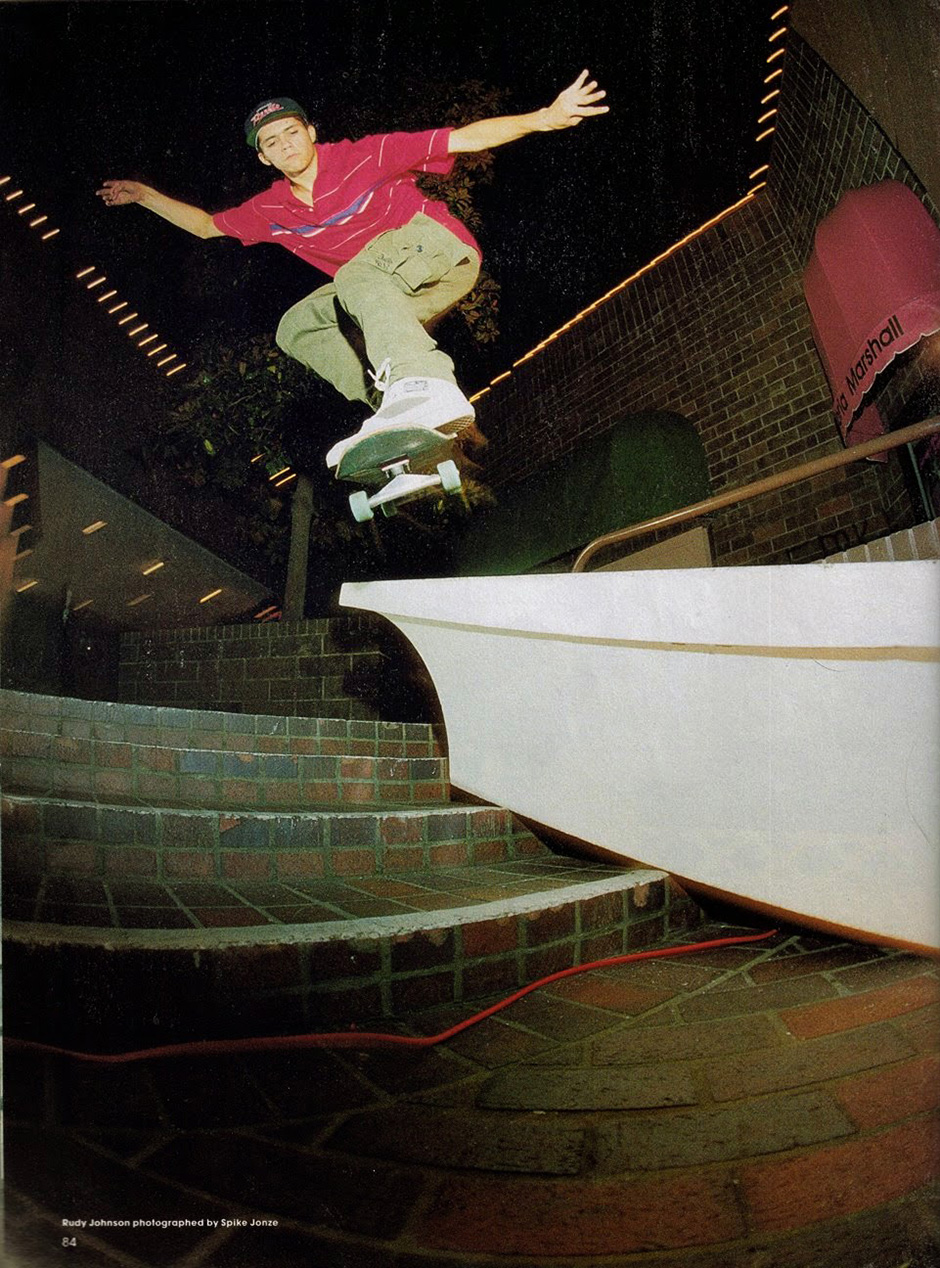

Rudy Johnson – Blind Skateboards: Video Days (1991)

I met Rudy Johnson in the spring of 1990 at the Powell Peralta Quartermaster Cup. I met Guy [Mariano], Rudy [Johnson], and Gabriel [Rodriguez] at the same time at the same contest. It was either the Am Jam or the Quartermaster Cup. I’m not sure which came first. I had traveled to Santa Barbara with people from Palo Alto, and it was the first time I had ever driven that far away from my home. I was 16, and I was turning 17 in June. I think I got a speeding ticket on the way down there, and I got a speeding ticket on the way back. But when I was at that event at the Powell headquarters in Santa Barbara, I was just this young, eager kid with a camera. I just started filming and photographing everyone who ripped at that event, and I really formed a connection with Guy, Rudy, and Gabriel.

Like typical “Jake Rosenberg” from that era, I got their phone numbers and their mail addresses. Then, when I got home, I sent them all their footage that I shot of them. I stayed in touch with them, then later into the summer, I saw them again at another Powell event. Then Rudy shared with me all of this footage that he had filmed with his friends from when he was young. This was from prior to getting on Powell, and then when he was on Powell. So I edited this 10-minute video of Rudy’s early days of skateboarding, and I set it to The Beatles. It was sort of a part that I put together for him because I had been doing a lot of these parts for my friends, and I was sharing them with people. So I edited his part, and I sent it down to him. That tape kind of made the rounds. I think I showed it or gave a copy to Mike Carroll. Then anyone who stays at Mike Carroll’s house sees it. So Rudy, for me, was in that group, and he was one of the kindest and most generous people that I encountered.

Two Jacob Rosenberg photos of Rudy Johnson taken at the Powell Quartermaster Cup in 1990 on the day they first met

Then Rudy and Guy invited me to LA to film for Video Days in December of 1990, right during my Christmas and New Year’s break, and I went down with my video camera because I had developed this rapport with them. I’m filming, and then all of a sudden, now I’m in the car with Mark Gonzales and Jason Lee, and with Guy, Rudy, and Gabriel. We’re prancing all over Los Angeles and I’m filming, so for me, Rudy just holds an incredibly special place in my heart, and I’ve always just loved watching him skateboard. The Dinosaur Jr. cover his part is edited to was so good because we all listened to Dinosaur Jr., and then The Cure were such a beautiful emo band that a lot of us emotionally connected to, although maybe you wouldn’t always admit to people that you listened to that. There was just an alchemy that came together with that part. For me, Gonz’s part is amazing, like, irrefutable. Guy and Jason, amazing, but with Rudy, that was my guy.

Two tricks from the tape Jacob Rosenberg edited for Rudy Johnson

I took so many photos of him, and I had so many conversations with him. I stayed at his house, and his mother made us breakfast in the morning. So when Video Days came out and I saw Rudy’s part, I just felt so energised. It was like, oh my God, I haven’t seen any of these tricks! When there’s a skater that you love watching skate, and then you see them skating, and doing tricks that you haven’t seen them do, there’s just this beautiful feeling that we all feel when we watch skate videos. Rudy was, from a human standpoint, kind of my favourite skater at that time.

“I took so many photos of him, and I had so many conversations with him. I stayed at his house, and his mother made us breakfast in the morning. So when Video Days came out and I saw Rudy’s part, I just felt so energised”

When I drove down to L.A. I think Rick Ibaseta joined me, and I dropped him off in Costa Mesa. Then we met up with those guys. We stayed at Mark [Gonzales]’s house one night, then we drove across town and ended up staying at Rudy [Johnson]’s house for a couple of nights. And then we’re over at Guy [Mariano]’s. It really was almost like a dream, a dream where you project that something is larger than life and beautiful. But it was really like a dream where everything was just kind of happening, and you’re not really aware of how valuable or how meaningful these moments are until you’re older. Just the way that those guys welcomed me, the way that Spike [Jonze] treated me at the time, the way that Mark [Gonzales] and Jason [Lee] treated me at the time. They weren’t dicks to me, they were kind to me and grateful that I was filming them. In a couple of instances, Mark stood up for me when Guy was teasing me about being a chubby kid.

I think I have a couple of tricks that I filmed in Rudy’s part. He has tricks on those brick banks downtown, the tight tranny brick banks. I think there’s two tricks that Rudy does there that I filmed him do. I wish I had that tape because there’s other stuff on that tape too. There aren’t ten lost tapes because I have almost everything, but there are like five lost tapes. There’s a tape from Video Days that I filmed on that has us skating the Palladium with the parking lot, and George Michael comes out of the Palladium, and Mark almost runs into him. Then they’re skating the handrail on the opposite side of the street to the Palladium, and then we’re skating downtown at those banks, and also skating at the Manhattan Beach parking garage. I’m not sure if I was filming at Mark’s house, I would have had the camera on all the time, so I’m curious. There would have been other stuff, like I would have been filming in the car and all those other things.

I think I have a couple of tricks that I filmed in Rudy’s part. He has tricks on those brick banks downtown, the tight tranny brick banks. I think there’s two tricks that Rudy does there that I filmed him do. I wish I had that tape because there’s other stuff on that tape too. There aren’t ten lost tapes because I have almost everything, but there are like five lost tapes. There’s a tape from Video Days that I filmed on that has us skating the Palladium with the parking lot, and George Michael comes out of the Palladium, and Mark almost runs into him. Then they’re skating the handrail on the opposite side of the street to the Palladium, and then we’re skating downtown at those banks, and also skating at the Manhattan Beach parking garage. I’m not sure if I was filming at Mark’s house, I would have had the camera on all the time, so I’m curious. There would have been other stuff, like I would have been filming in the car and all those other things.

I think that Video Days is properly romanticised for all the right reasons but with Rudy [Johnson] he really just did not have a ton of video parts. He has this white whale video part that i edited, i didn’t film the part that i edited of him but there were always clips his friends filmed of him and he’s just so rad. He would do ollie tail smacks on this little quarter pipe in a parking lot. Then he would do like backside Ollie onto a curb, onto like uh the front of a building. So he’d ollie up the kerb, and he would do like 180 arc, and then do a 360 flip off the curb on the other side with a sort of a walkway in the middle, just super rad tricks where you’re like, oh my God, this guy is so good. He skated in an era where for the people who were good, the reason they skated transition was because at those NSA and CASL contests, they always had some transition element as a part of those street style contests. You kind of had to be decent at transition during that era. Everyone could do blunt to pivot fakie, and all these nice lip tricks. All the tail smacks and the other stuff on little mini ramps and quarter pipes. They would never show up some place and say I can’t skate that. No, they could skate it.

There’s even footage of Rudy skating the Pacific Design Center, the building is still there, the staircase isn’t exactly there, but I just love the way he does all the one foots. I love the way he does nose bonks. There’s the Spike [Jonze] photo from this part as well, I mean, I had that on my wall, the back lip down the white bench, it’s just beautiful, especially with the extension cord in the shot. That’s a detail to me, I’m sure everyone saw it, but maybe it didn’t matter to them. It mattered to me because it showed that they had lights. They actually plugged in some lights to film because back then, you would bring lights on a battery with you, or you would park your car and point your car lights at the spot at night so that you could skate it and film it.

Extension cord and polo coordination. Rudy Johnson backside lipslides. Spike Jonze shoots

I don’t have a specific memory of seeing Video Days for the first time. I do remember getting a copy because I filmed for it, and they sent me one. I remember getting that copy pretty soon, too. I don’t think there was ever a premiere; the video just kind of came out. The biggest sort of screening was at that Powell demo or contest, where everyone slept there and spent the night. They called it the “Lock-in”, where everyone kind of was locked into the skate zone at Powell, and everyone watched Video Days together that night because someone had a tape. I don’t remember watching it for the first time. I just remember getting the tape and seeing my name in the credits, which was always a “pinch me” thing, you know. Also, in 1991, when that video came out, it took a long time to come out. I think they were filming for a really long time. I had just started to have footage come out. I had footage in the New Deal video [Useless Wooden Toys], and I got a credit in that before Video Days. Right around that time, I was starting to be credited in a bunch of videos that were coming out. I had footage in The Planet Earth video [Now ’N’ Later], credits for making the Dogtown video [DTS], making the Think video [Partners in Crime], and then filming for the bLind video. So it was really good for me personally and professionally. I say professionally with a wink, and a nod, and quotations but because people saw my name, they knew if they filmed with me, their footage might end up somewhere. Those milestones were really, really important.

Mark Gonzales – Blind Skateboards: Video Days (1991)

The handrail stuff to me in 90 and 91 was always so amazing, you know, and really the beautiful thing with that boardslide, it was just so unexpected in the part. It’s not necessarily hyper-focused on. There aren’t two angles, there’s not a slow-mo, just all of a sudden you cut, and he’s skating in an area where you’re like, where’s this going? And then immediately that’s a fucking big rail. I think at that time we were all experts in the size of a rail, and who had done what? I mean Frankie Hill was sort of a rail king at that time. And of course, no one knew about what Pat Duffy was gonna be doing next. But I feel like the way that rail and that boardslide is positioned in the part is so understated. And then how he lands, you can tell that he’s just like millimetres away from his board shooting out and him Wilsoning, but he shifts his body perfectly, and you can just see kind of how hard he had to push his board through the kink. He really got on before the kink, he went through the kink, he goes down the other slant, and then he lands it, and he’s squatted. And I mean, I can see that whole trick. So if you’re asking me to identify a trick, I can see it so clearly, the rail I think is brown, and there’s just a style around it.

I think that’s one of the reasons why Video Days is so special, because it wasn’t necessarily about trying to build this part that emoted something. You might have one of the gnarliest tricks in the part, not at the end, or not at the beginning. And I think, obviously, the school of videos that I came up under with Mike Ternasky, that was not the structure that I learned, or that I’ve been successful in implementing in the videos that I’ve made. But something about that is so charming, and so authentic, and so honest. I think that is really what makes that a special, special trick. And it really pushed everyone. You’re just like, oh shit, now we’re looking for kinked rails for sure. Mark is doing hippy jumps in that video; he’s skating mini ramps, he’s skating vert ramps, he’s skating a kinked handrail. I mean, it’s an ATV part, which is kind of under-discussed; it’s all in there.

The clearest memories I have of filming with Mark [Gonzales] are because I have that footage, but there are a couple of other ones. We filmed at Kenter, which is obviously a really amazing, historic skate spot school, and I didn’t know the history of it with Dogtown and [Craig] Stecyk, and Stacey [Peralta] when we were filming there. I really didn’t understand the context of that place, but he’s doing switchstance 50-50 to half cab out, or switch 180 out on the bench. He was also trying these really weird tricks on the bench itself on the flatground. I also remember driving on the 110 or the 710 from his house in Huntington Beach, and he was driving my car because I didn’t know where to go. The traffic was so bad, it was just a standstill, and Mark just pulled over into the side lane and just drove in the side lane. He just didn’t care, just drove, and drove two, three, or four miles past all this standstill traffic. He just drove and drove, and then eventually took an exit, and we went up to skate that brick transition spot downtown. So I just remember his energy, you could tell that he just loves skateboarding, and he had this gift.

The clearest memories I have of filming with Mark [Gonzales] are because I have that footage, but there are a couple of other ones. We filmed at Kenter, which is obviously a really amazing, historic skate spot school, and I didn’t know the history of it with Dogtown and [Craig] Stecyk, and Stacey [Peralta] when we were filming there. I really didn’t understand the context of that place, but he’s doing switchstance 50-50 to half cab out, or switch 180 out on the bench. He was also trying these really weird tricks on the bench itself on the flatground. I also remember driving on the 110 or the 710 from his house in Huntington Beach, and he was driving my car because I didn’t know where to go. The traffic was so bad, it was just a standstill, and Mark just pulled over into the side lane and just drove in the side lane. He just didn’t care, just drove, and drove two, three, or four miles past all this standstill traffic. He just drove and drove, and then eventually took an exit, and we went up to skate that brick transition spot downtown. So I just remember his energy, you could tell that he just loves skateboarding, and he had this gift.

I also think like that crew of guys, with Jason [Lee], Guy [Mariano], Rudy [Johnson], and I will say Gabriel [Rodriguez] was with us that day too, so I lump all of those guys in together. There are different ages in that group of guys, but they’re really peers skating together in all different styles. None of those guys are redundant to each other. And I think that was such a beautiful moment because with Mark, you can just see how much energy he’s getting from these younger guys. He was always very curious and interested, and connected, and he had a kindness to him. Then his creativity on a skateboard would just kind of take you aback. And then he would always talk to people who were walking by. And I’m from the H-Street era of filming and talking to pedestrians, so I love that shit, and so I would film him talking to people, which was really special.

Mark had a nose for talent for sure. I think that anyone who saw a Guy [Mariano], and Rudy [Johnson], and Gabriel [Rodriguez] would just want to be around them, and knew that they were gonna change skateboarding. It was the same thing if you were around like Mike [Carroll] and Henry [Sanchez] in San Francisco, and Rick Ibasetta and Jovontae [Turner]. You knew that these were the guys. Then in San Jose, you know, Salman Agah, Sean Mandoli, Jason Adams, Spencer Fujimoto, Edward Devera, you knew those were the guys. Tim Brauch, Tony Henry, it was clear. That list starts to expand very quickly. But it was Guy, and Rudy, and Gabriel, and Paulo [Diaz]. I don’t remember Paulo being around as much in those days, but I know they were all close. When it started to shift towards bLind, I just remember Guy, Rudy, and Gabriel skating a lot.

“Mark is doing hippy jumps in that video; he’s skating mini ramps, he’s skating vert ramps, he’s skating a kinked handrail. I mean, it’s an ATV part, which is kind of under-discussed; it’s all in there”

I don’t think I was aware that I was a part of something that would be historically catalogued. But I was aware that I was filming with who I perceived to be the best skaters. It wasn’t lost on me, I was desiring to be around better, and better, and better skateboarders. When I saw Guy and Rudy at the quartermaster cup, I 100 % was like, these guys are fucking rad. I want their address. I want their phone number. I’m going to film them. I’m going to shoot photos. I’m going to send them prints. I’m going to send them tapes. Then I would call them, and I’d write them letters, and they would write me letters. And so I was 100 % aware of the talent that I was pushing towards. I don’t think I ever looked at it as gravitas. I think I looked at it as I want to be around this type of a contributor, and to me, it was just so evident that the tide was changing.

The kids were taking over with all due respect, except the guys like Matt Hensley, Mark Gonzalez, and Ed Templeton, those are really cream of the crop street pros. I was aware that there was this young group that was my age that I had access to. They were changing the vocabulary of what you would do, and that really didn’t give a fuck. They would dress the way they wanted to dress, they would listen to the music they wanted to listen to, they would do the tricks that they thought were cool, and they would not do the tricks that they thought weren’t cool. So very quickly, if you saw other people skating and they weren’t doing those tricks, it’s like, why aren’t they doing those cool tricks? It wasn’t such a conscious thought, but you were aware of that. And again, there’s no shade on that previous generation, to be very clear. It was more about the fact that a professional skater in that era was not someone that I had easy access to. But the top amateur skater? If I had a camera and I wanted to film them, I could. All the pros are getting all the coverage, and all these young kids sometimes they would get coverage. Henry Sanchez gets the cover of Thrasher magazine. But if Henry’s not riding for companies that are under High Speed Productions or Ermico, does he get that cover? Probably not. They put him on the cover because they’re turning him pro, and they’re showcasing a skater that they see as this new generation. Even after Henry gets the cover, it’s not like every magazine, every issue was full of all the young bucks and skating street.

What you quickly realise about the making of videos is that the majority of tricks that you see in a video were done six to nine months before you saw the video. So we see Ban This, and then we see Guy and Rudy, and they’re just light years ahead of what we just saw in Ban This, light years! I didn’t understand that at the time. I think I was just like, “Oh my God, these guys are so good!” So I think it almost hyper-accentuated their talent, but it was a little bit of a misperception because, of course, they’re good, and that was nine months prior. Also, I was filming these guys for multiple days. With Mike Carroll, we filmed for a year together for Questionable, and we had tons and tons and tons of footage. Those guys, when they would film for Powell, would get a couple of days or a couple of weekends here and there. And if you didn’t land it, then it wasn’t going to be in the video. When I started filming, and we would start thinking about what tricks we wanted to get, if we didn’t get it today, we’re not gonna give up on it. We’re gonna go back and make sure we get it. The progression is hyper-evident when Questionable came out because a lot of people didn’t even get that video until three or four months after the video was released. By then, most of the tricks were six months old at that point. Not to wedge Embarcadero into this conversation, but that’s why Embarcadero was so important. Because even without a video coming out to benchmark it, the difference of one to two months in terms of what tricks people were doing was massive at Embarcadero.

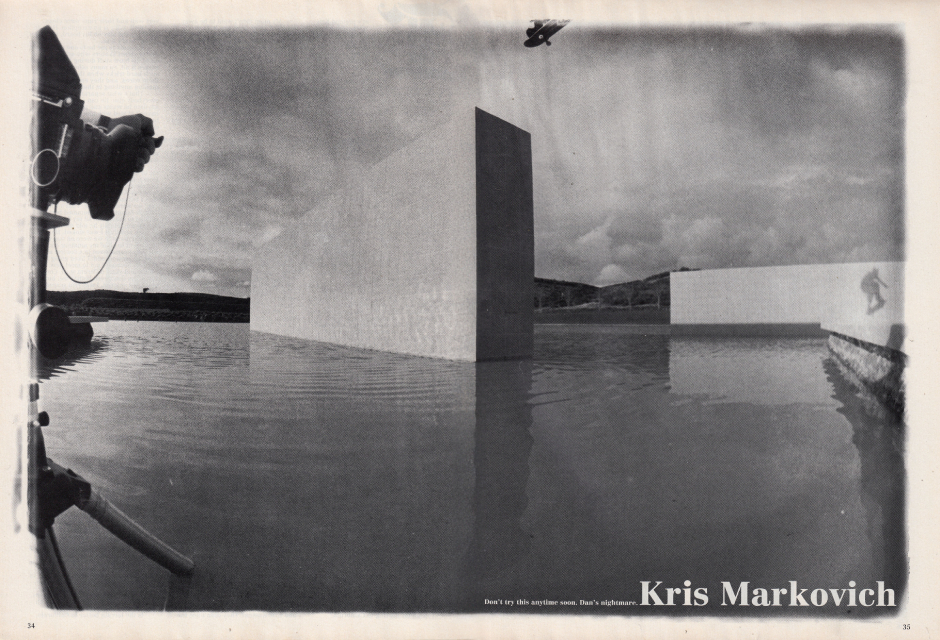

Kris Markovich. PH: Daniel Harold Sturt (1992)

I’m aware of [Daniel Harold] Sturt from his filming for H-Street and Life with Mike Ternasky. Because I was around Mike Carroll all the time, I saw rough cuts or in-progress cuts of stuff for H-Street, and Not The New H-Street video took so long to make. There were all these different versions of it that I kind of saw, and I could see that Sturt was using reflectors to light the skaters, mostly on ramps, but sometimes in the street, he had the reflector up, which was really amazing. I think that this [Kris] Markovich photo is so alluring, the spot is more of a focus than Markovich, and you have the burned edges of the frame, the ominous quality of it, and the artistic quality of it. During this era, you’re calibrated with the Spike Jonze fisheye, this drifting shutter that’s so kind of beautiful, and sharp, and in focus, but feels very in the life. Then, of course, you have the Grant Brittain, kind of pristine, Ansel Adams-esque, just incredible composition and big photographs that are in that big Powell Perala conversation. Then in San Francisco, you have Bryce Kanights and Kevin Thatcher and MoFo [Mörizen Föche] and Tobin [Yelland] that have a little bit more of that street grime and a bit of an edge to it. Sturt is, in my opinion, this insane new voice that just comes in like a sledgehammer.

The video footage that he’s shooting is amazing, and then all these photos that he’s shooting are amazing. He shot a bunch of photos for Matt Hensley’s interview, his pro spotlight in Transworld. I think that with the photograph we are talking about here, there was a level of artistic leaning that progressed what we interpreted a skate photo could be. The spot itself was so weird because you’re asking how did he get up there? It’s an ollie, it wasn’t a kickflip, you know. I hate to use the word creative, but it was so creative and so expressive in this era. Skateboarding is the type of thing that you just need to see one glimpse through a new door, and it opens up a whole world. I think [Daniel Harold] Sturt opened up a whole world and pushed a lot of people who were visually in skateboarding to maybe think a little bit more outside the box.

“I think that this [Kris] Markovich photo is so alluring, the spot is more of a focus than Markovich, and you have the burned edges of the frame, the ominous quality of it, and the artistic quality of it”

I was interviewing a very famous musician, a legendary music producer [Quincy Jones], and we had finished the interviews, and I hung out with him for like two hours after the interview. He said to me, “Jacob, there are no rules”. It was so profound because this individual was so right. It was a realisation that that’s kind of what my life has been, but I needed to hear that out loud to remind myself that there are no rules. Then, when I reflected on Mike [Ternasky] and the values that he embodied, I realised that Mike’s life really abided by no rules. He was 21 years old, and he wanted to quit college; he wanted to go start this company, and he does it. He starts this company, he wants to sponsor all these young kids, he does it. He wants to make a skate video; he’d never made a video before, but he does it. He wants to do all these traveling tours with these skaters; he’s never done the tour before, but he does it. He wants to split off and do this new company. He wants to make new videos and all this stuff. He does it. So I think that there’s a real empowerment when you hear that thing out loud. I was at the Museum of the Moving Image when I shared that sentiment, but it was nothing that Mike ever said to me. It was just when I looked back and reflected on his essence, I realised that what this music producer shared with me was what I came to understand the essence of Mike’s being to be.

“Sturt is, in my opinion, this insane new voice that just comes in like a sledgehammer”

As far as Sturt’s photography inspiring me, I knew that I could never shoot a photo like that. I did have a dark room in a closet at my house, and I was developing my own stuff and liked a lot of what Sturt was doing, edge burning and stuff in the dark room, and really interesting stuff. Polaroid stuff where you tear one side of it so the exposure is ripped off. It was always very evident to me that, from a photography standpoint, I just didn’t have quite the DNA that my peers had. So I think I was inspired by the photography that I saw, I just don’t think I was able to ever emulate it, other than maybe trying to frame things a certain way. When you get into the habit of trying to emulate something as opposed to just keeping the spirit of the idea close, and then just being you. If you try to emulate it too much, it’s never gonna land because the impulse is not your natural expression. So I think for me, this photo was just really inspiring, and it kind of hit me on the head a little bit. There are more ways that we can showcase what we’re doing, and to a degree, I think that certainly impacted the way that we approached Virtual Reality. That opening montage was, you know what, fuck it. All these people want all this footage, they want all these bangers. There’s such a huge expectation with this part. Well, let’s just fucking start it and show all the gnarliest tricks, but on tiny screens, and make people have to look between all these screens and just fuck them up. I think part of that was a radical mindset that comes and has seeds in that Sturt Markovich photo. So to me, that’s the beautiful nature of progression. It’s not one plus one equals two. It’s one plus one equals three equals five equals seven, you know, because you just don’t know the ways in which that cracks something in your mind.

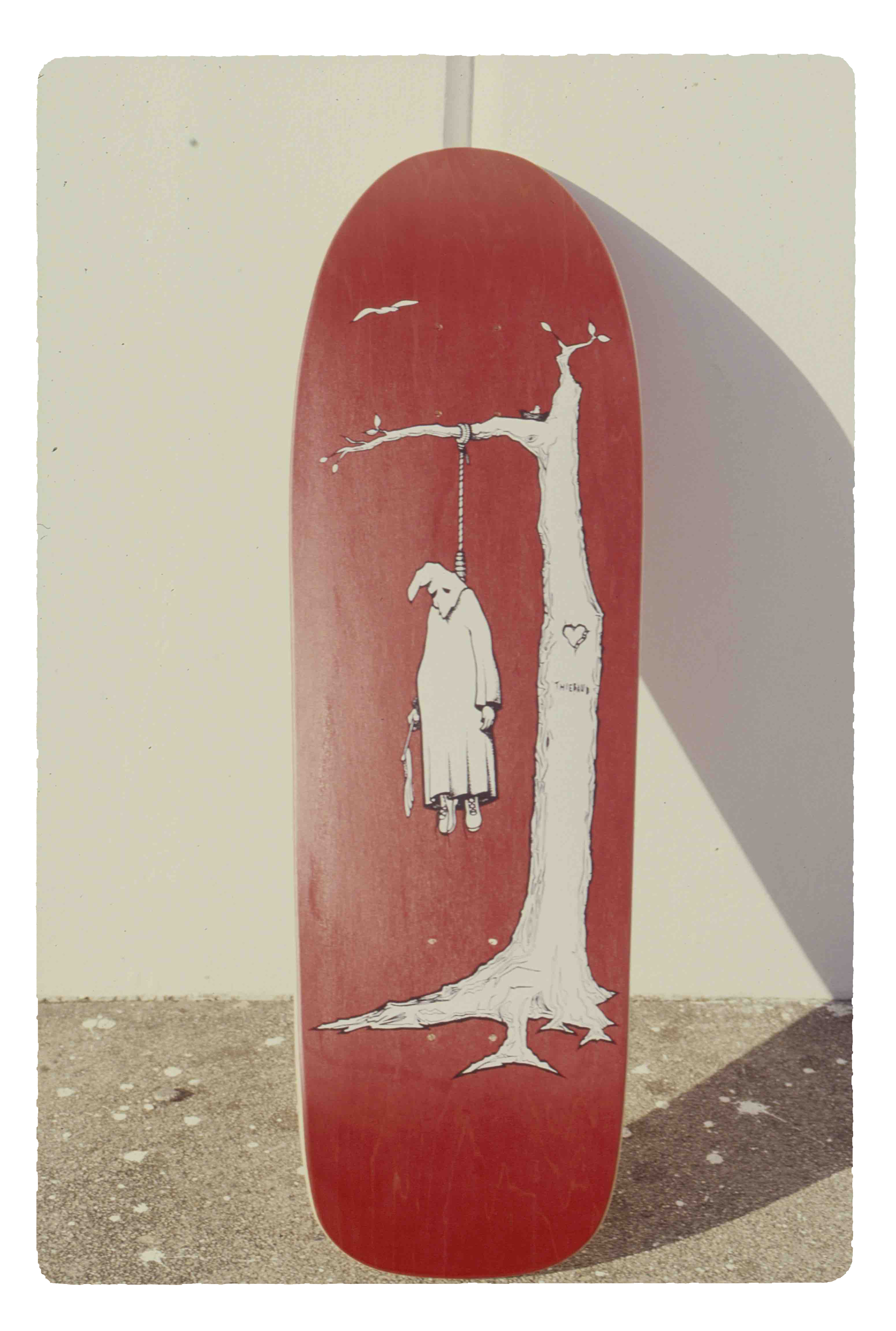

Real Skateboards – Jim Thiebaud “Hanging Klansman” (1991)

I think skateboarding at its best is an incredible place for a sense of counterculture activism in terms of the spirit of what skateboarders embody. I say that with a little bit of biting cynicism, having seen people negatively comment on Thrasher’s most recent post about some of the horrific stuff that’s going on in this country. These are the same people who were so stoked on the Hanging Klansman graphic. How far have we slipped? I grew up listening to Public Enemy. I adored and revered Chuck D., and that led me to reading the autobiography of Malcolm X. Jim Thiebaud used to have that Public Enemy beanie; he had these journals and books that he was releasing, and I had a connection to him from skate camp in 1988. If you know Jim, he has a very soft voice, but he’s a really beautiful standup human being who believes in things with a purity, and a sense of what’s right, and a sense of justice, and a sense of respect.

I think skateboarding at its best is an incredible place for a sense of counterculture activism in terms of the spirit of what skateboarders embody. I say that with a little bit of biting cynicism, having seen people negatively comment on Thrasher’s most recent post about some of the horrific stuff that’s going on in this country. These are the same people who were so stoked on the Hanging Klansman graphic. How far have we slipped? I grew up listening to Public Enemy. I adored and revered Chuck D., and that led me to reading the autobiography of Malcolm X. Jim Thiebaud used to have that Public Enemy beanie; he had these journals and books that he was releasing, and I had a connection to him from skate camp in 1988. If you know Jim, he has a very soft voice, but he’s a really beautiful standup human being who believes in things with a purity, and a sense of what’s right, and a sense of justice, and a sense of respect.

There was this French magazine that I was working for, and I did a profile of Real Skateboards. I remember the TG graphic came out, that Tommy Guerrero TG graphic. Then the Hanging Klansman came out, and I remember seeing it, and it almost took your breath away. You’re so proud to be a skateboarder and to see an image like that. That’s a skateboard graphic that says something so deep and so powerful. This is the era of Rodney King; this is 90, 91, and there are racial tensions. There was the Bensonhurst murder in New York. There’s a lot of stuff going on and a lot of chatter, and there’s this weird climate. Then Jim [Thiebaud] puts out this board that just cuts like a hot knife through all the noise and says, “No, you know what, fuck all that shit. This is just wrong”. To be on that side of the argument, there is no argument; it’s just ignorance. Because the way the world is going, and the way that things build. We are an inclusive country that was founded in a very messy way with people who have been ill-treated for centuries. Fuck the ideology that doesn’t respect the humanity of these people. The Hanging Klansman is like a bullseye to that notion.

I love Jim; he means so much to me, and provides so much motivation, comfort, and support of me over the years. I just think, in the history of skateboarding, if you’re going to pick the top three graphics, that’s got to be in the top three. There are graphics that are memorable that you may put in the top five skate graphics, but then there are graphics that said something that was a lot bigger than skateboarding. Jim gave me his board with trucks and wheels and everything at the end of skate camp, just gave it to me. These small gestures move mountains for people later in their life because I was just an insecure kid, trying to find my way, and Jim saw in me what I needed to see in myself. When someone makes a gesture like that, there are these building blocks of self-confidence. Maybe I deserved to get that? You don’t think about “entitlement”, was I deserving to get that deck, but you ask what about me? Why did I get that? I must’ve been cool, and I was always interested, and curious, and talking to everybody. So that must be the way because this guy just endorsed me. Those are priceless moments. For me, that’s why I answer my DMs, and I respond to people, and I connect with people, and I don’t really ever want to feel above something. Sometimes it gets a little overwhelming because I just don’t want to be on the platform that much, and I feel obligated to respond to people, but I know that sometimes a little nudge, or a little feedback, or a little response means so much more to that person than you could imagine.

“You’re so proud to be a skateboarder and to see an image like that. That’s a skateboard graphic that says something so deep and so powerful”

Jacob’s own “Hanging Klansman” board shot for a REAL skateboards article that ran in NoWay magazine

I did have one of these boards in my collection, a brand new board which I kept. I regret it, but I eventually traded it for a Mark Gonzales board because I rode those early Mark Gonzales boards, and I sort of wanted to make sure I had all of those boards in my collection. As far as boards I was using to film on, prior to Plan B, I was skating a Think board from Greg Carroll, and prior to Think, I was skating a Dogtown board from Dogtown because I was helping them make their video. Then, prior to that, I think I was skating an H-Street board that I had either gotten from Mike Ternasky or Mike Carroll. Prior to that time, I would have been skating Gonz boards and Steve Caballero boards. When filming during this era, I ended up getting some Think boards from Greg [Carroll] that were blank, and I just put tons of stickers on them. My wheels weren’t as small as everybody else’s, but they would have been below 50 millimetre for sure. I would have been riding K-9 wheels because of Dogtown, then I’d be riding Venture trucks because of Venture, and then maybe riding Spitfire wheels after that. It would have been Plan B wheels and Plan B decks after that. I still have three of my original boards. I have my Caballero, which is the big dragon, not the Chinese menu dragon. Then I have the Gonz two-face board, which I have photos of skating. And then I have another board that I got that would be from this era, which I think I got from Ryan Monahan. He skated vert on it, and he gave it to me. My first ever board was a blue Tony Hawk with white Rib Bones rails, Rat Bones wheels, which I still have, and Independent trucks. Then my second board was a Lester Kasai.

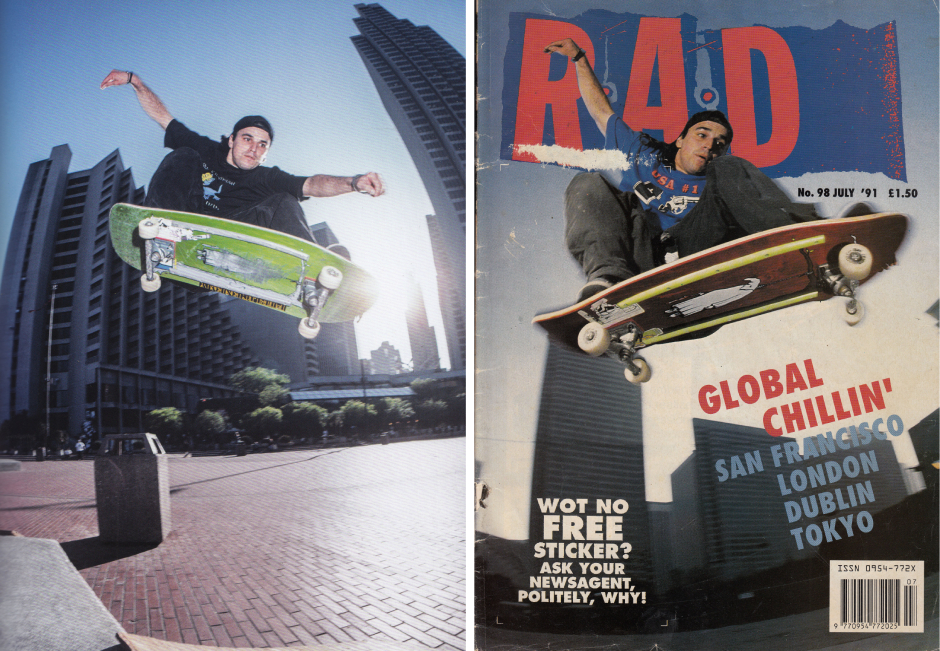

Two Jim Thiebaud San Francisco sighings on his “Hanging Klansman” Real pro model designed by Natas Kaupas and Kevin Ancell. Makeshift Embarcadero hip ollie and the July 1991 cover of R.A.D. PH: Luke Ogden

I would see Jim [Thiebaud] at Embarcadero during this era, but rarely skating. He would have pretty much been working at Deluxe 9 to 5. So if I went over to High Speed back then, it wasn’t even called Deluxe yet, he would be at High Speed in the REAL area. Then Venture and Think were out near the foundry in a totally different part of Hunter’s Point, where they actually made the trucks. If I were over at Thrasher, or in that shipping area with REAL, Thunder, and Spitfire, I’d see him there if I went by there. Or if I were with a skater from REAL, and they needed to pick up a board or something like that, they might go over there. That might have been where they were doing the silk screening as well, if memory serves me correctly. Jim, at that time, was definitely still skating, still a pro, but by 92 he’s more like a company guy feeling. He and Mike Ternasky were friends from skate camp, because Jim was a counsellor and Mike was the camp director. But I saw them a little bit more as peers than Jim as like a hardcore skater. You would still see photos and see stuff. I think it was hard for some of those guys to come around because they’re not skating at the same intensity that they were in the ’80s and into ’89 and ’90. You know, 91 is a really, a real demarcation, things change in that year. And those guys all start to sure up their businesses and really focus on that because the industry is starting to radically contract. So I think that’s when they’re starting to think about making sure their companies do well, and sponsoring these young riders.

I just don’t see how anyone could not see what’s happening now as a fascist movement with a centralisation of power, and a suffocation of opposing voices. Our country has always thrived on our constitutional rights, and those rights seem to be infringed upon, and those rights seem not to be as important, conveniently, to people in power. I think that in that process, you see a dehumanisation of people who you don’t agree with, and it’s incredibly sad, it’s incredibly depressing, and it needs to continue to be unifying towards people who believe in the good of things. We’ve always been a flawed country, and I think our flaws are as great as ever right now. I think there are those of us who believe in the ideals of America being founded through immigrants, and the country was built on the back of a massive slave population. Why would you, and how could you erase that? That’s what they want to do: erase that history; they want to cleanse it. They want to change it, and they want to oppose the voices that speak out against it. That’s the fight that we’re in right now. People are wearing masks right now, they’re just not wearing the hoods. I was in the middle of my show, and a man was murdered in the streets of America in Minneapolis. I was promoting my show, but it felt weird, and I had to say something about it.

The contents of Jacob Rosenberg’s EPICENTER book which encapsulates a golden era

Your incredible new book has launched, and as we speak you have just returned from the official closing of the show in San Francisco. Is there a sense of closure right now?

I think there’s more of a sense of closure than there’s ever been. I think the projection of closure is that everything’s like a nice neat bow, and it’s like everything’s in a box. I think the feelings will always be a part of me, and the nostalgia for that spot will always be a part of me. I remember at the opening of the show on the last night that James Kelch was in San Francisco, I walked over to the bricks with him, and I filmed him at the bricks, and I interviewed him, and I took a bunch of photos of him lying on the bricks at night. I just kind of allowed myself to feel everything that I felt in that moment, and I was able to express to him how much he means to me, for all the kids that he stood up for, and I wanted him to know why I dedicated the book to him and to Tommy [Guerrero]. He shared that he felt that he was okay now. He was like, “Okay, I’m good now, I can go home. I’ve had this experience”. He felt as much closure as he was going to feel is sort of what he shared.

I stayed a number of days after James left before I went home. But after that night, and after the opening, and connecting with everyone, and doing all these interviews with everyone, I also felt like I’m okay to say goodbye to this. Then, when it came to the closing, I drove up in a car with Mike [Carroll] and Greg Carroll, and with this kid Jackson [Roth], who is a young filmmaker who works for me. We spent six and a half hours in the car with the Carroll brothers driving on the I-5. We stopped at Harris Ranch, which is where I would always stop with Mike Ternasky. The Carroll brothers don’t spend a ton of time together, the three of us don’t spend a ton of time together, but we were in the car together, sharing stories. Mike is hearing things from Greg that he hasn’t heard before, and Mike is sharing things that Greg hasn’t heard, and I’m this very safe, objective witness to all of this. Then we get to the show, and Rick Ibaseta is there, and Rick kind of started that moment for me, at least to be included in that crowd, because he kind of approved me when I was filming him for New Deal back then. Kind of the first time I really filmed at EMB was with him for Useless Wooden Toys, and we had a really beautiful conversation that night amongst all these people. It was really quiet, and everyone was listening, and Greg [Carroll] shared some beautiful stuff, and Mike [Carroll] shared some beautiful stuff, I shared very meaningful stuff, and Ted [Barrow] did an incredible job of contextualising everything.

“I was able to express to him how much he means to me, for all the kids that he stood up for, and I wanted him to know why I dedicated the book to him and to Tommy [Guerrero]”

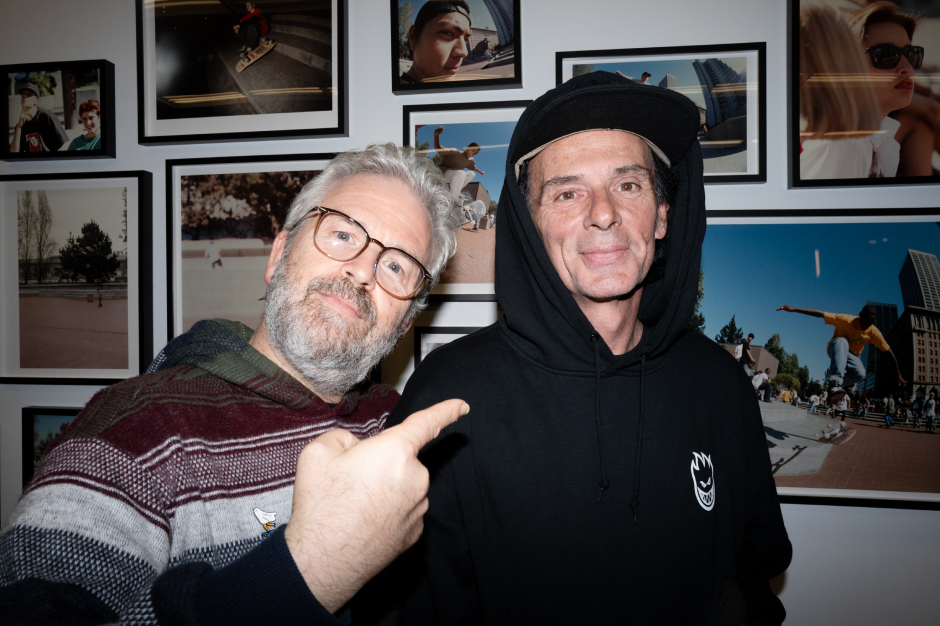

Jacob Rosenberg and James Kelch on opening night. PH: Stephen Vanasco

We woke up the next morning and did another series of interviews. I got to interview Mike Archimedes, who was arguably the first person to ever skate at EMB. It was good to get that on the record, him and Shrewgy [Steve Ruge] together. Then I just walked through the plaza and had lunch with Mike and Greg over at the Ferry Building, and we walked back to the galley, gave each other hugs, said “I love you”, and then they jumped on a plane back to LA. I walked through the plaza, and I had a little screwdriver and hammer, and kind of chipped up a couple of pieces of some bricks and some pieces of grout that were loose enough for me to get. I’m not going to take stock in the fact that I’ll be able to get a brick because who knows how policed that situation will be.

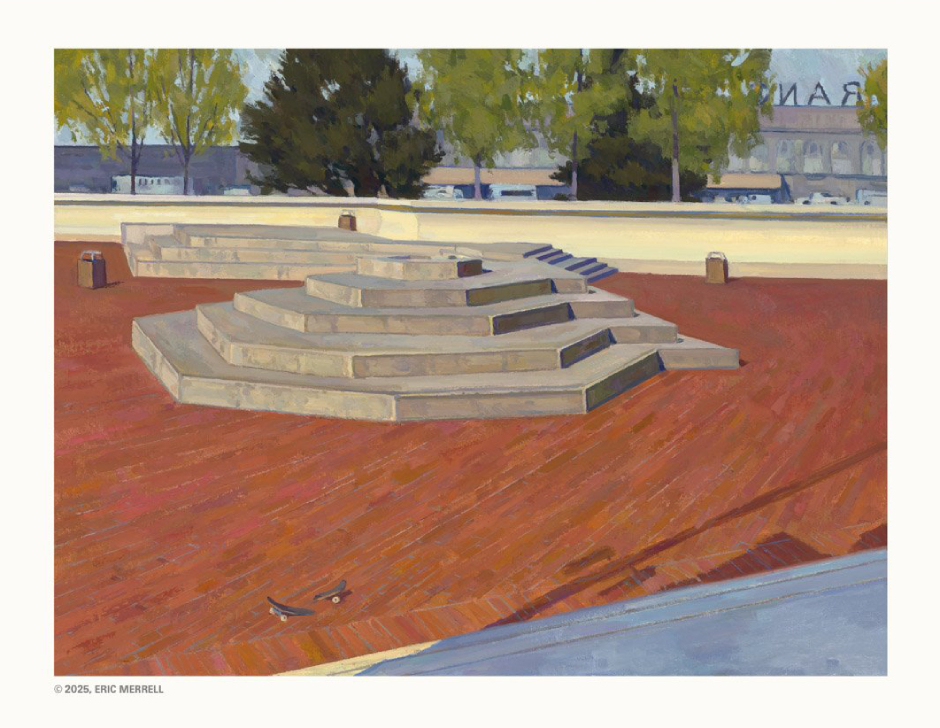

Eric Merrell’s painting of Embarcadero, a print which accompanies the first edition of the EPICENTER book

How do you feel about the show?

It feels like we did it right. GCS Agency was this incredible backdrop. Victor from the gallery and James, who is kind of his right-hand man, were fantastic. Everyone who came through just really felt it. I worked really hard on making sure the video was all stuff that people hadn’t seen, and the photos certainly people haven’t really seen before. Some photos that aren’t in the book, and some photos that have never even been put out there, were a part of the show. I think for me, the show stirred the right feelings. It also evoked a bigger conversation with the city, people from parks and rec, people from the public library, historians, and people from newspapers and publications. It really helped plant a flag for skateboarding at Embarcadero, being as important as the fountain that they’re going to tear out, because those were talked about in tandem. That was really the goal with the book when Ted [Barrow] pushed me to make it.

So, to talk about closure, I feel like I did my job, and my job was to make sure that the people from the era were recognised, that the conversation amongst the city of San Francisco was stirred, and that skateboarding at Embarcadero was elevated in its respect amongst peers and non-skateboarders. I think that we were successful in doing that. From there, I saw so many people, I hugged so many people, and I cried with so many people. It all started with just deciding that it was time to make this book, having my designer, Alexander Hansford, and my creative director and editor, Greg Hunt, and with us building that book and getting the contributors that we got.

As an outsider looking in, it seems to me from what I’ve seen of the opening and the closing that you’ve also teed up chapter two. You’ve brought all these people together again in a positive way, and you’ve reignited friendships and the underlying passion that formed them.

I don’t look at it as chapter two; I look at it as a family reunion that had the right framework around it. I think that everyone has felt a certain way about Embarcadero. I would never want to take away from other plazas and other skate spots in America, or globally at the time, but the simple fact is that Embarcadero was the pacemaker for the rest of the world of technical street skating, and how fast it was changing. You have Love, and you have Pulaski, and you have Brooklyn Banks, and you have plazas in different places. But a lot of those scenes became a bit more pronounced when the main skaters from those plazas came and traveled to EMB and felt everything there, and were accepted there, and then went back and took it back to the plazas that they were from. Everybody wanted to have an EMB in their town after that. But I think the reason why EMB was what it was was because we had all the footage, we had filmed so much stuff there, so you could actually see it.

“my job was to make sure that the people from the era were recognised, that the conversation amongst the city of San Francisco was stirred, and that skateboarding at Embarcadero was elevated in its respect amongst peers and non-skateboarders”

That’s why you can never say it’s the only place because there are plenty of places that didn’t have the filming. But the filming became an essential component of the culture at Embacadero, and it was peers filming each other, right? Someone my age filming other people my age and then putting that footage out there. When those guys visited and then went back, I’m sure they’re really making sure they have filmers more than they did before, because that was sort of synonymous with EMB after that certain point. And this beautiful year of 1991 is mostly just me and Mike Carroll. I’m filming a lot of other people in the Plaza, of course, for the Think video and the Dogtown video. But I have a year with him there, where there really aren’t many other people who are filming. Aaron Meza comes in maybe early ’92, and he’s filming in late ’91, but from a day-to-day basis in ’91, it’s really just me going there on a continual basis.

I asked Mike Carroll, when I spoke to him, if there was any footage or any photos that he was surprised to see, and he said that he was fairly familiar with most of the material, and expected that volume of imagery, but was there anything you were shocked to see yourself or had forgotten about capturing?

When Mike did that interview with you, he hadn’t seen everything at the show. When he went to the closing event on that last day, he actually sat in this area called the chapel, which is like a private room where you can watch raw footage, and he was just blown away by what he saw. He doesn’t remember how many tricks he did when he was barefoot skating in the plaza. He stressed, and was just so pissed that he skated with one shoe. He only skated with his front foot shoe, and he was doing nollie flips with just a sock on his back foot. It’s insane, he’s doing trick after trick. That line where he does the kickflip up the three stairs, he almost landed that with no back shoe, no lie, it was absolutely insane. That was just because he was stressing. He remembers so much; he has a really good memory for a lot of that stuff. But with some of that stuff, he’s like, did I imagine it or did I see it? Like that one trick he spoke about with you, where he blacked out and just did the frontside flip down the little three in that line that we filmed together. But then he saw the footage, and he was like, okay, I am remembering it correctly. He also mentions the fakie 360 flip frontside noseslide attempt, where he was so pissed that he couldn’t get it, so he just went and landed a nollie flip down the big three first try, literally, and that footage is in there too!

Jacob’s footage of Ronnie Bertino trying a frontside bigspin to backside bluntslide at Embarcadero

Can you think of any other ‘close but no cigar’ Embarcadero moments that would have made a dent in the progression history books?

Ronnie Bertino’s bigspin bluntslide, and Ronnie Bertino’s noseblunt slide frontside big spin out. Mike Carroll almost landed a fakie 360 flip down the seven in the summer of ’92. Keenan Milton landed a backside 180 kickflip down the seven. No one has ever seen that footage. I don’t know why I didn’t transfer it, but it was probably because Mikey didn’t land the fakie 360 flip that he was trying at that time. Keenan broke two boards, and that backside 180 flip is arguably before Sal [Barbier] landed his backside 180 flip because it’s the summer of ’92, and Keith Hufnagel is filming Keenan for Fun skateboards.

It’s amazing that Ted Barrow is able to take this whole conversation and help it make the most noise in a civic way, while also romanticising the spot map of SF and its significance with those city walks. Have there been any positive developments from Ted’s dialogue with the powers that be?

I mean, when you consider that they’re gonna demolish the entire plaza and rip up the bricks, and they’re gonna demolish the fountain and take that out entirely, I don’t know how anything could be positive after that. I think that thankfully, they’re starting to recognise how important skateboarding is, and there may be space for helping expand that narrative, but I don’t know about the plans for the plaza and how they plan on integrating skateboarding. I think all that skaters are asking is that skateboarding was there in the beginning, so just whatever you make, just make room for skateboarding. It doesn’t have to be EMB, just make room for it. It would be amazing if you put a ledge with some bricks by it that was just sort of there that skaters could skate, or maybe a little skate park area. I’m not in those conversations, so I can’t speak to that; that’s just hopeful me, but that’s where all of that is. This project one hundred percent backed up everything that Ted had been saying to them, on the right size of a stage. Ted and this group Docomomo have been saying preservation, preservation, preservation, this history is important. But then the show itself reinforced that this is a big deal.

Jacob’s footage of Keenan Milton and Mike Carroll skating the seven at Embarcadero

Would you say the show has changed their perspective at all?

I don’t know, they’ve acknowledged this, but they’re also acknowledging it after they’ve decided to demolish it and also decided to remove the fountain.

Who was it the most unbelievable to see again, or to see together with someone else from this whole thing?

Chef Pierre showed up for the closing, and Pierre is just an incredible figurehead from the history of skateboarding in San Francisco; he was always at EMB, always around EMB. The fact that we were able to get James [Kelch] out of Ohio and have him agree to fly out was a huge deal. As far as surprising people, there were just so many people that came out of the woodwork. I wouldn’t be able to recognise all of those people because I’m not an EMB local. I was the right filmer at the right time, with the right passion. But all of those guys who are locals, who represent multiple generations of Embarcadero skaters, they all shared with me how stoked they were to see so many different people from so many different eras. There are different crews. There’s CBS crew from San Francisco, and then there’s THK, and THK was one of the strong crews in the early days when EMB started to be more skated. A lot of THK guys were there, and that was really important to me.

Jacob Rosenberg, Rick Ibaseta, Greg Carroll, Mike Carroll, and James Kelch. PH: Stephen Vanasco

I really wanted to make it clear I wasn’t trying to do a culture grab. I wasn’t trying to make a book that was telling you the whole comprehensive history of EMB, and that I’m the one who knows that history. It’s like, no, this is 1990 to 1993. This is everything that transpired in front of my lens and the people that impacted me, and I’m going to use this opportunity to shine a light on the backdrop itself because it’s going to be gone soon. The feedback that I got from those OGs was just gratitude and being stoked to see so many old friends. I think Chef Pierre being there was amazing. Ron Allen was there, and that’s always amazing. Those legendary skaters from that era came through.

You talk about Embarcadero being the right place at the right time, but the timing of this love letter to the spot is also exactly the right time.

Yeah, you have just got to trust those things. I was always reluctant to put out a book about Embarcadero just because of how sensitive it is in terms of the ownership of who was there, and who has the right to talk about it. But the book is very personal; it’s from my point of view, and I’m not claiming anything that is not mine to claim. I’m making sure to shine a light on important people who are the reason why that spot is important.

Will you be doing a second run of books?

Yeah, we’re working on a second edition right now, and I think that edition will have mostly the same content. It will have slightly different packaging, though. The slip sleeve books were really an investment to do. For the second printing, I’d love to be at a lower price point so that more people could access the book, and so that I could get it into shops and stuff like that. I tried to make the first book as cheap as possible, given how expensive it was to make. So the second book will be a singular hardcover book with both the written section and the photo section separated by different types of paper. It will still feel like the exact same conversation, just a slightly different presentation that allows there to be a little bit of a difference between the first edition and the second edition.

So we’ll be expecting the second edition in skate shops?

Yeah, and it is the goal to have that second edition out by the summer.

Jacob’s photo of James Kelch – the mayor of Embarcadero was wheat pasted around the city

With a little time to reflect on the project, do you have a personal favourite image at this moment in time?

It was almost my favourite image going into the book, and it’s kind of still my favourite image coming out of the book. There’s a slightly blurry photo of James Kelch walking through the plaza, looking over his shoulder at me. Not over at me, but he’s looking at someone sitting down, and he’s walking through the plaza. It’s so bright, and kind of overexposed, and an imperfect photo, and it’s slightly out of focus. I always felt like that photo kind of captured how elusive our memories are, how it’s not crisp and perfect, and he’s kind of in motion and blurry. But now, when I look at that photo, and I see him looking back. I now kind of think that he’s looking back at us from the era. Before, I used to think of it as looking like a memory, but now it looks like there’s a bit more finality and a reflection.

Amazing, thanks for your time, Jake.

No problem. Thank you.

We want to thank Jacob Rosenberg for his time, and for the wealth of contributions to our culture. If you missed out on the first edition of EPICENTER make sure you’re one of the first to scoop the second edition when it is released by signing up HERE.

Be sure to follow Jacob Rosenberg and Ted Barrow for more future updates about this project and the future of Embarcadero.

Thanks to Neil Macdonald [Science Vs. Life] for the mag scans, Pete Thompson for the portrait, and Stephen Vanasco for the gallery shots.

Other notable Jacob Rosenberg interviews: Chromeball Interview #137 , Monster Children , The Nine Club , Podus Operandi , Intro to EPICENTER.

Previous Visuals Interviews: Gabriel Summers , Mark Suciu , Hayley Wilson , Mike Sinclair , Tom Delion , Sam Narvaez , Tyler Bledsoe , Daniel Wheatley , Braden Hoban , Jaime Owens , Charlie Munro , Lev Tanju , Jack Curtin , Ted Barrow , Dave Mackey , Jack Brooks , Korahn Gayle , Will Miles , Kevin Marks , Joe Gavin , Chewy Cannon