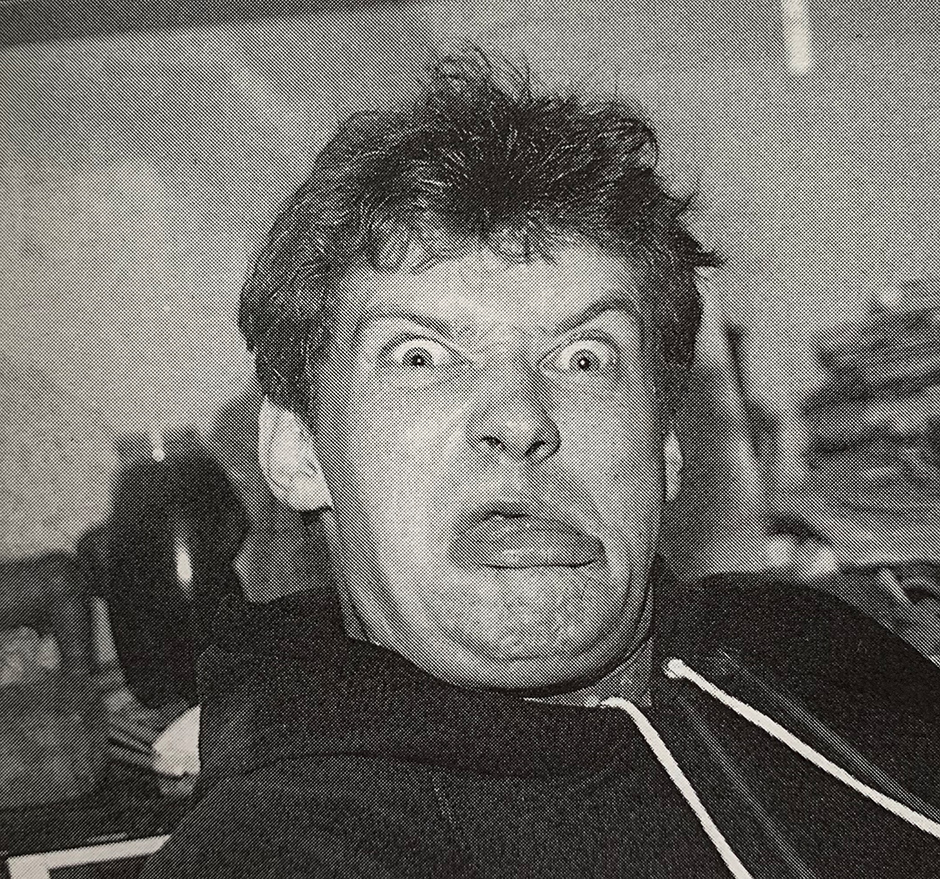

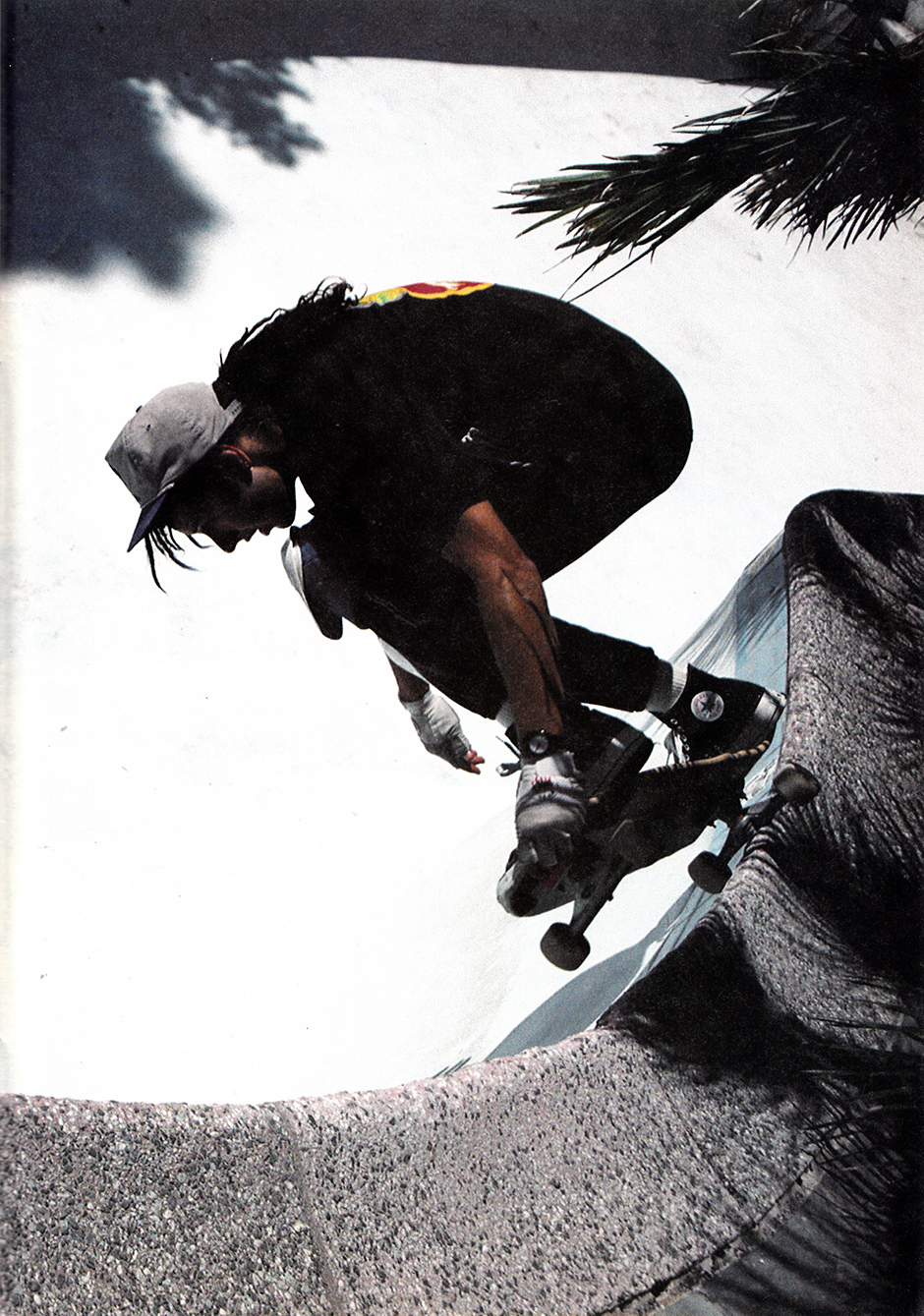

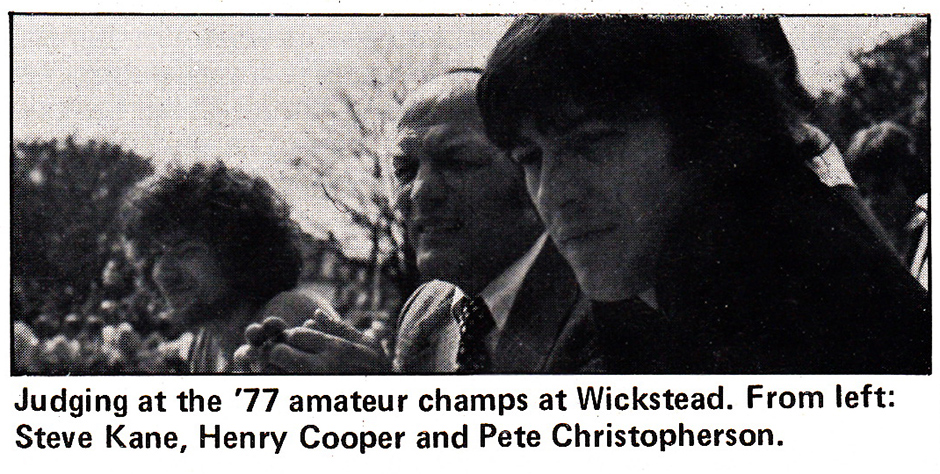

INTERVIEW BY NEIL MACDONALD (@SCIENCEVERSUSLIFE) / PORTRAIT of Skateboard! Editor Steve Kane in 1989

Steve Kane, now in his mid-60s, might not be immediately familiar to everybody but the mark he made on UK skateboard culture should be. From having what might be the first documented flip trick (certainly the first documented double kickflip) to his time at the editorial helm of the second-generation Skateboard! magazine between 1988 and 1990, Steve’s contributions to our culture may have been a decade apart and many years ago, but these were the times UK skateboarding was going through two of its most fundamental and long-lasting changes.

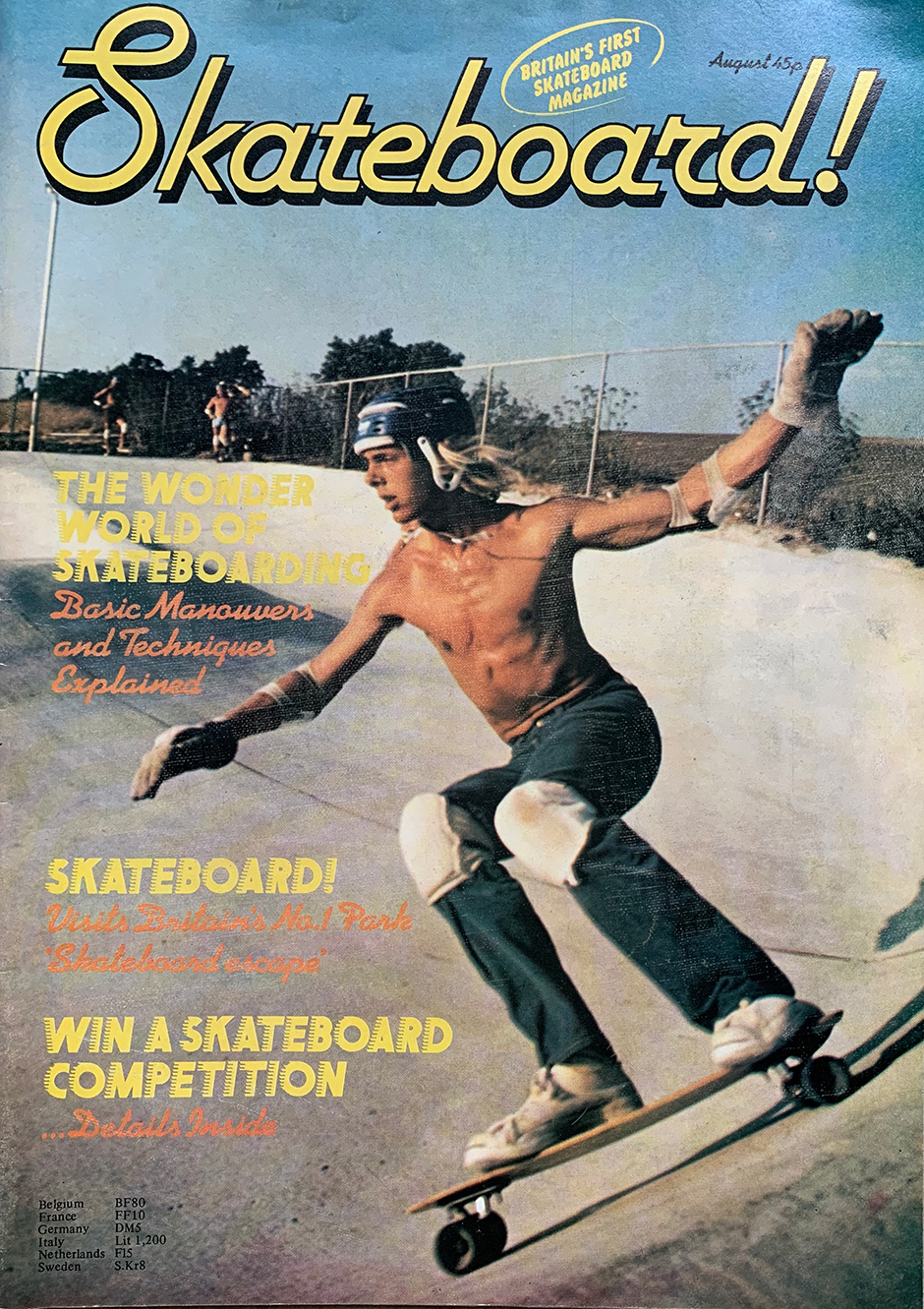

Steve was skating, and contributing to the first iteration of Skateboard! magazine, when the UK skateboard scene was reshaping this fun, new, sun-bleached Californian import into something altogether more suited to British weather and terrain in terms of hardware, style, spot, trick selection and media. When finding or building your own place to skate was half the battle, and when specialist skateboard shops barely existed on these shores, the context in which skateboarding existed was a unique one, one where local scenes and unknowns were every bit as relevant as what was going on at Upland or Venice Beach, and it was one worth talking about.

When skateboarding’s late-80s boom rolled around, Steve was ready to go as editor of the rejuvenated second version of Skateboard! magazine, with a different staff, publisher, and an outlook more suited to where skateboarding was beginning to find itself – in the hands of the skateboarders. While this reprise of the title entered a marketplace already occupied by the brilliant RaD magazine, Steve set out to do something different, on his own terms – and encouraged the same from his readership. The magazine laid out the facts on the imported product flooding the marketplace, went on no-budget trips to the middle of nowhere and published the blueprints for making everything from ramps to rails. It turns out that such feverish single-mindedness takes its toll, because just as the street revolution that Steve had predicted began to take over skateboarding, and with skateboarders themselves seizing control of the industry, he left the magazine and skateboarding for good, leaving assistant editor Ian ‘Meany’ Lawton in charge until the magazine folded in 1992.

I called him up at his home–2,000ft up the Portuguese mountain where he’s lived for the last twenty-eight years–to find out what went on.

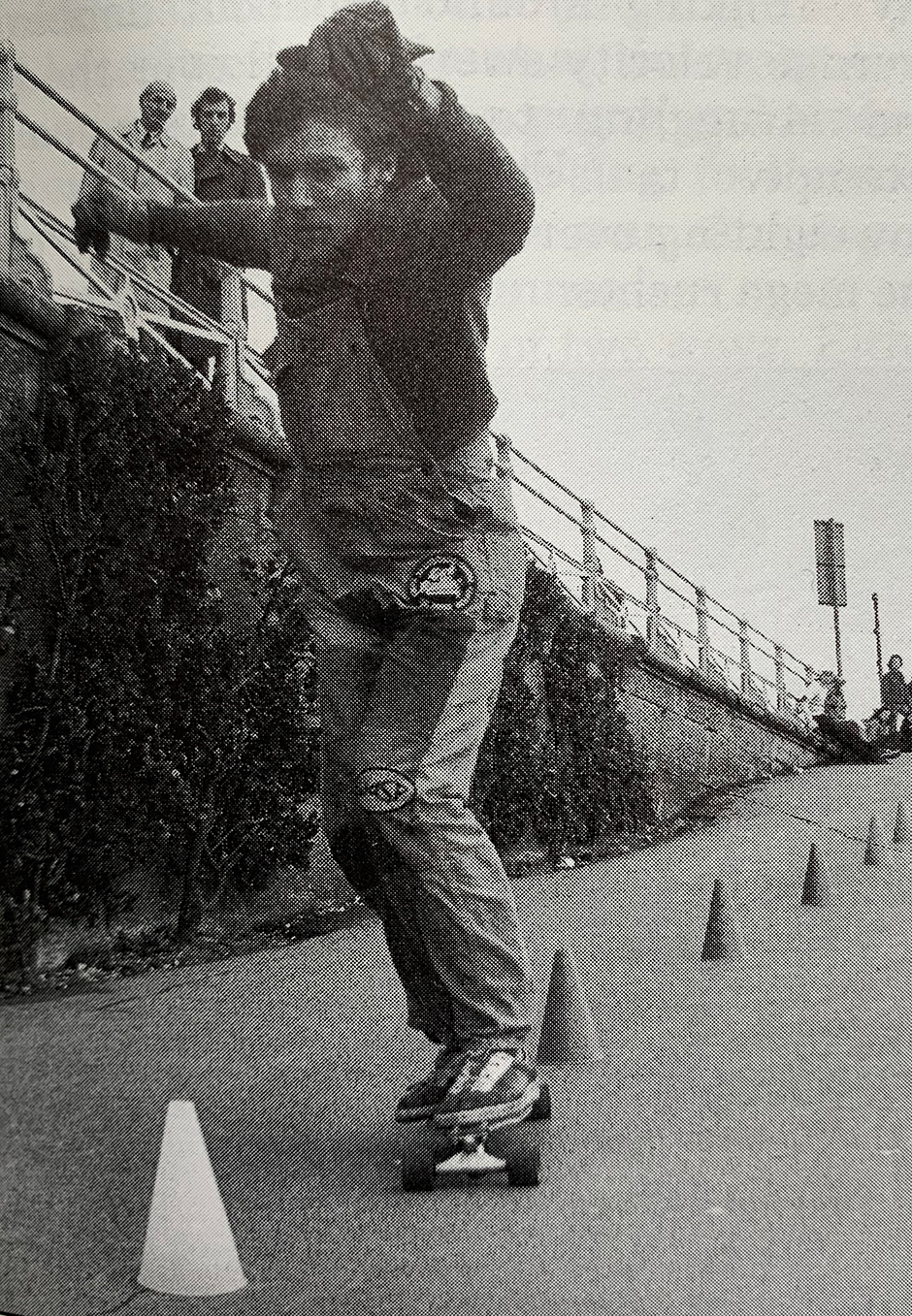

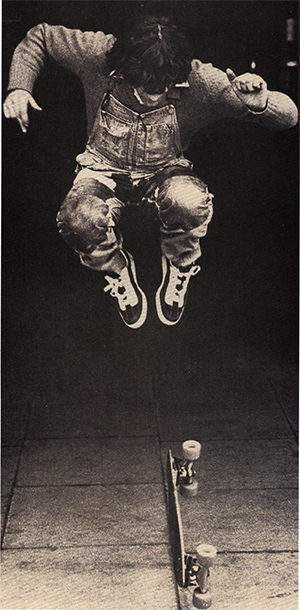

Steve Kane seventies slalom action. Photo: Robert Vente. Inset below left – Steve’s double flip at Southbank. the first documented flip trick?

So you’ve just had double knee surgery. How are you, and was that skate-related?

Originally, yeah. From back in the mid-70s when we started, from when we didn’t wear pads. You’d just go down on your kneecaps. We didn’t even know how to fall, so you’d put out your hands instead of rolling and a lot of people got a lot of wrist injuries, and then when pads came out they were just like basketball pads, so just a lump of foam. Later on an orthopaedic surgeon told me that was actually worse, because although they stopped it hurting as much, the force transmitted onto your kneecap was just as bad which made it worse because you wouldn’t stop doing it. It was only when hard shell pads came out, with a hard foam doughnut on them that took the force of the impact off the kneecap itself, that they started to actually mean something.

Way back in my early 20s it already felt like someone was sticking needles into my kneecaps, so yeah, it started back then, but I’ve been an obsessive walker since I left school.

I had no idea.

Yeah. I went to a very privileged school where I had a scholarship in science, but I got pissed off and left at 16, and I went up to Scotland, to Kintyre, where I herded sheep and planted trees mainly. I spent a lot of time with shepherds there, and walked miles and miles and miles. I’ve always done that since and that’s why I didn’t skate when I came here to the mountains, because not only was there no tarmac, but when there was tarmac it was terrifyingly steep and I’d got to an age where I wasn’t going to go for that.

I think it’s a skateboarder thing: it’s not about whether it hurts, it’s about whether you mind that it hurts

So I’ve worn the bloody things out. There wasn’t any functioning cartilage, the meniscus had gone and I was still walking on them. I think it’s a skateboarder thing: it’s not about whether it hurts, it’s about whether you mind that it hurts. I just had to have it done and I said to the surgeon at the time that since one knee is totally fucked and the other is absolutely fucked, why not just do them both on the same day, but it was four and a half hours under a local anaesthetic, conscious, with these guys hacking and sawing away at my knees. It was pretty grim.

What do you do for four hours while that’s happening to you?

Just lie there, slightly tranquilised! I was listening to them have this sort of builder’s conversation. The main surgeon who was doing it was some genius specialist, some star surgeon who’s known overseas, and he had these new implants that give a much more natural mobility while the older ones are just hinges, really. He was explaining to the other surgeon what he was doing all the time, which was a bit gruesome at times. “There’s not enough good bone here, you’re going to have to drill it more”, and things like that.

The bit that goes on the cap of the femur, they’d tap it in with a hammer, then tap it out again because it wasn’t quite right, then give it a huge whack and of course I didn’t feel the pain but I could feel the bone being driven into the hip joint. It’s like being kneecapped under anaesthetic and then being put back together again.

After a while I had to say to the anaesthetist that I could do with some more drugs.

All worthwhile in the end, right?

I had to do it. It was doing my body in and doing my head in. I had an opportunity to skate about three years ago, and skated into the town, and thought I was doing pretty well. I went back the next day, to this big wide avenue with planters and pedestrians, and I was kind of slaloming down there, getting pretty stoked for an old man, and thought I should push back up the hill a bit harder to get some exercise, and then whaaang my Achilles went, and my tendons went, and I couldn’t walk at all. I had to get on my skateboard and kind of glide down to where my wife could pick me up.

She’d have been thrilled.

I found out that the hospital where I had the operation done was just around the corner from there, but it was new so I didn’t know about it at the time so I went to a cafe where I could have breakfast while I waited for my wife to come and take me to the other hospital.

You did the first documented flip trick, right? In the original UK version of Skateboard! magazine.

I was already writing for the magazine at that time, and they were short of material. There was lots happening but they didn’t really understand how the magazine should be, and they didn’t really want it to be a copy of Skateboarder. Felix Dennis who published it did Oz magazine, so had experience of an underground magazine, but then they created some motorbike titles so they saw it very differently. They were keen on the product, and they knew that kids and consumers could get ripped off by manufacturers so they needed someone who could say, ‘Actually, this is shit, don’t buy it’, or ‘You should get this, even though it doesn’t look very fancy’.

I was already writing for the magazine at that time, and they were short of material. There was lots happening but they didn’t really understand how the magazine should be, and they didn’t really want it to be a copy of Skateboarder. Felix Dennis who published it did Oz magazine, so had experience of an underground magazine, but then they created some motorbike titles so they saw it very differently. They were keen on the product, and they knew that kids and consumers could get ripped off by manufacturers so they needed someone who could say, ‘Actually, this is shit, don’t buy it’, or ‘You should get this, even though it doesn’t look very fancy’.

They used to use fashion photographers because there were no skate photographers at the time and sports photographers couldn’t get it, they couldn’t get the timing and composition and so on, so they got this guy called William Finnegan who was a fashion photographer and we went off down to Southbank. It was pissing with rain so we couldn’t do anything like proper skating, but from pissing around in moments like that I’d learned how to double kickflip. Basically if you want to let it go round twice, you need to get up high! So that was the only photograph we could take really, in quite poor light on a small dry patch with the rain pissing down, but we wanted to do it at Southbank because it’s Southbank and that’s where we do that stuff.

The first time I went down to Southbank there were maybe only a dozen people there who’d ‘found’ it, so to speak. The original people: Jeremy Henderson, John Sablosky, people like that. I was taken there by Rocky Brann and we bumped into David Goldsmith who worked at Alpine Sports and had been asked to start up the magazine by Felix and Bruce Sawford, and he was desperate for other people because most skaters were about 14 years old, and even if they were articulate they didn’t know they were. So I said I’d do it, even if I thought I couldn’t.

‘I’ll figure it out!’

Yeah! ‘This is what I need to be doing!’

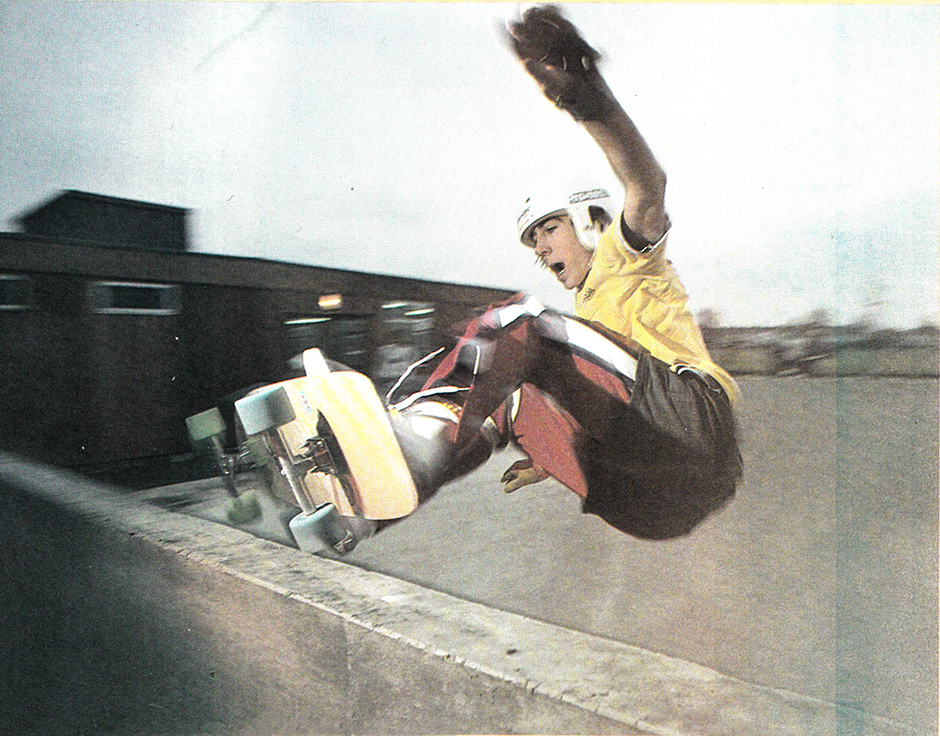

Uk Original John Sablosky tail blocks at New Barn in Brighton in 1978. Photo: Robert Vente

When did you first see skateboarding?

I’d very briefly been in the army and got on one of these job-creation schemes, and London University were doing a land use survey of Surrey. I’d been a country boy and knew the difference between wheat and barley, but the other job-creation types were geology or geography graduates and they didn’t care very much and they didn’t know shit so I ended up supervising them, running around checking on them. Alice Coleman was the professor and one of her things was land use, and also non-owned space in the city, how there were places in the city that had been built but didn’t belong to anybody, so were like wasteland.

I got interested in skateboarding because there were these urban kids treating that wasteland like posh people treat the mountains for skiing or surfers treat the sea. When I first saw skateboarding I realised why it was important. No names, but other people came along later and made a living out of making that observation.

I got interested in skateboarding because there were these urban kids treating that wasteland like posh people treat the mountains for skiing or surfers treat the sea

Issue one of Skateboard! magazine launched in 1977

You’re talking about Ian Borden?

He refuses to acknowledge that I said that first. I mentioned it once but didn’t push the point, so he’s made a career out of it and I don’t give a shit; instead of making a career out of it I got involved in skateboarding, and got involved in the magazine which seemed much more important because that was about telling skateboarders what it was about, rather than telling architects and academics what it was about. I didn’t give a shit about them but I wanted to tell skateboarders that what they were doing was really important. It really matters. It’s historic and it’s not a sport.

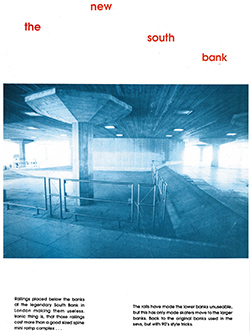

At that time I considered it a performance art, but not one to be done in front of an audience. It was a semi-private performance art, but it had a kind of ritual magic to it… People would come together in this place which was—on the face of it—a hard and hostile place underneath this Brutalist building down on Southbank that no-one gave a shit about, or other places like that, and turn it into a temple. That’s why I’m not into the whole theme park-isation of the new Southbank, with all the graffiti which is nothing to do with the culture but was around at the same time.

Go on…

I first came in contact with people doing the graffiti thing in Bristol, from 3D [of Massive Attack] and Banksy, and they had skateboarding connections because they hung out with the same people at Bristol Skateboard Centre right at the beginning. When I went down to Bristol with the mag first time, I remember in Clifton Village thinking, “Shit, something’s happened here”.

I first came in contact with people doing the graffiti thing in Bristol, from 3D [of Massive Attack] and Banksy, and they had skateboarding connections because they hung out with the same people at Bristol Skateboard Centre right at the beginning. When I went down to Bristol with the mag first time, I remember in Clifton Village thinking, “Shit, something’s happened here”.

Skateboarding in London started with hotdog skiers. Rocky Brann was a hotdog skier, and Dave Goldsmith was one too although he wasn’t as talented as Rocky, and they were ski instructors. One of them brought a slalom skateboard to the resort, the fancy rich-kids resort, and basically said, “Hey, this is a fun thing to do when it’s not snowing” or whatever. That was why it was Alpine Sports and people like that selling skateboards in London. Down in the southwest there were surfers doing it, but there was no connection between the two.

But then almost immediately skateboarding happened down at Southbank and at Hyde Park, and it included people who weren’t rich kids. Of course there were the Jeremy Hendersons and the John Sabloskys who obviously came from pretty privileged backgrounds but other kids had started to appear, very ordinary kids. There was also the involvement with art students, because there were a lot of art colleges around there, just north of the river, and at that point in London a lot of culture—punk and stuff—was coming out of the art colleges. Skateboarding’s always been really integrated with culture like that, but it’s always brought something else with it.

Jeremy Henderson gets airborne at harrow in 1979. Photo: TLB

So anyway, I went to Bristol, to Clifton, with Rocky who introduced me to the Bristol guys and there again it was rich kids who skied. These four old Etonians, former Bristol University students, who were members of the ‘Dangerous Sports Club’, this legendary club, and they were nuts. Completely fucking nuts but they were doing what posh kids should be doing because they shouldn’t be fucking running the country. They should be crossing Antartica with a tin of carrots, you know? Clowns like Boris Johnson should be fucking clowning.

they were doing what posh kids should be doing because they shouldn’t be fucking running the country. They should be crossing Antartica with a tin of carrots

Amazing.

At that point they were into windsurfing, which was really new, hang-gliding which was also really new and people died doing it then, and they were base jumping. Chris Hiatt Baker invented bungee jumping, sitting in his house watching a thing on TV about how these guys in New Guinea or New Caledonia or some place put on a display for the Queen where they tied these creepers to their legs and jumped. One of them kicked the bucket, and everybody else watching went, “Oh shit, fuck! That’s awful!”, and Chris was thinking, ‘That looks fun…’

He had this professional bungee cord that was used on boats, to tie yachts to the land or attach surfboards to their VW bus, and being an old Etonian he had a friend who was a physicist who did the maths for him. Ironically he was not in the first jump as he went to London to get his girlfriend, Janey and was late. They were nuts, and when they got the first set of big red Kryptonics they went to the top of the biggest hill they could find and just got straight on the board and went flying down. So they kind of jump-started that whole culture in Bristol.

There were a bunch of other people hanging around too, people like Nicky Wisternoff, whose son Jody then became a DJ [with Way out West] and there was Willy Wee, who was one of the young skateboarders who then formed part of The Wild Bunch and Massive Attack and stuff like that, and Royce Creacy who was a biker who later provided a lot of important technical input into both stages of Skateboard! magazine. He’d also been a Formula One engineer and he just had this great mind, you know?

There was definitely a lot of stuff going on in Bristol back then.

And it continued right on until it stopped, when Massive Attack stopped being cutting-edge and drum n’ bass stopped being original, but it was continuous for a long time.

When people tell the story of that, they forget about skateboarding, and the skateboarding was really important to it. Sitting in the Special K Cafe in ’88-ish—it got called Kosta’s because Kosta was the guy who ran it but its proper name was Special K—and there’s all of The Wild Bunch, and there’s Banksy who was just a snotty little schoolkid hanging around 3D because 3D was the graffiti guy in those days. 3D was incredibly patient with Banksy and I remember starting to see his stencils on the lamp posts between the cafe and St. Paul’s—and there was Ray Mighty and Nellee Hooper, all in this tiny cafe playing pool and drinking crap instant coffee, and I was in there too.

Willy Wee had introduced me to Kosta’s after my first marriage had packed in, and I ended up living in a room in somebody’s flat just up the hill from there so I’d always have my breakfast in there and I got friendly with Grant [Marshall, Daddy G of Massive Attack] when they were still The Wild Bunch, before they went off to Japan.

It was all happening and it was during that time that I started to get the second phase of the magazine together, and then I didn’t see Grant or the rest of them for a while because we were all off doing our shit. It was the same with Daniel Day-Lewis, I went to school with him but the last time I saw him was when he was doing publicity for My Beautiful Laundrette, because we all got so involved in what we were doing. When the magazine took off it just ate my life, you know?

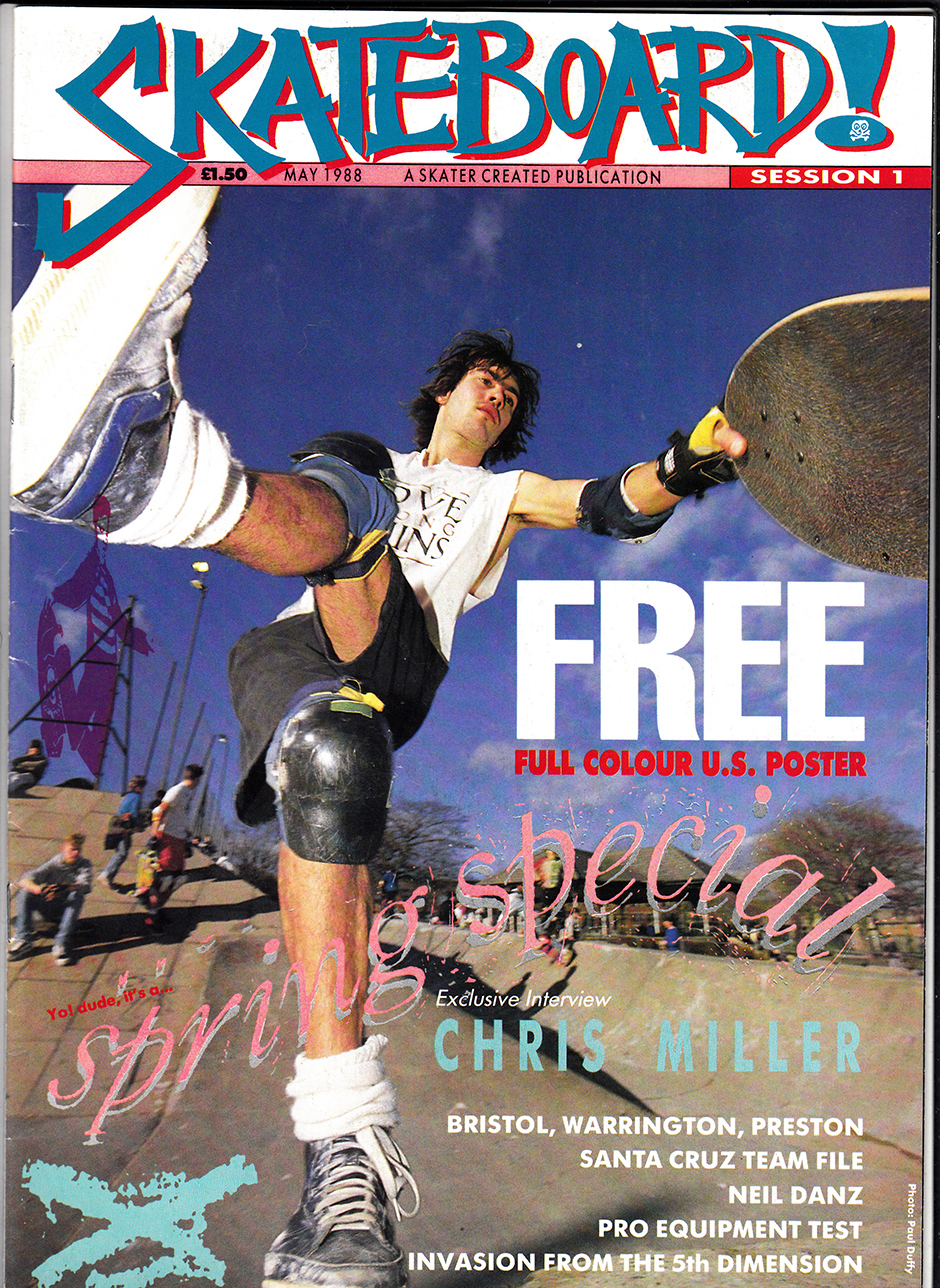

SKATEBOARD! Issue ONe – May 1988. Sqeez D’Souza snake run sweeper at Bedminster before he was hired. Photo: Paul Duffy

You were involved in politics in Bristol too, weren’t you?

Between the magazines I was very involved in politics; I was the chair of the branch that had Tony Benn and all those radical left-wingers, but I left very cynical, about that, so I left all together and got involved in some community things. I became an administrator at the Bristol Waldorf Steiner School in Clifton which was quite an experimental school. DJ Die, who was also a skater, was a pupil there and he was a real fucking tearaway! Haha!

All of this in between the two versions of Skateboard! magazine.

By this time Felix, the original publisher, had become a billionaire and Bruce Sawford the editor had become really decadent. It was sad. Skateboard! magazine had made Felix a lot of money—it sold something like 100,000 copies a month or something wild, or at least Felix was able to convince people that it did then he created a Mac computing magazine in America, and that made a fortune.

They tried to rip me off and I knew they were going to try to sell the title away without me, so I thought, ‘Fuck it’, and I got in touch with Mark Williams who had edited one of the bike magazines for Felix when I was doing Skateboard! first time round, and he was interested because he was one of the founders of IT [International Times], the other underground magazine at the same time as Oz, and he was a founder of Bike magazine which was the cutting-edge magazine that set the pattern for that kind of new consumer magazine that wasn’t just publishing the blurb from the manufacturers.

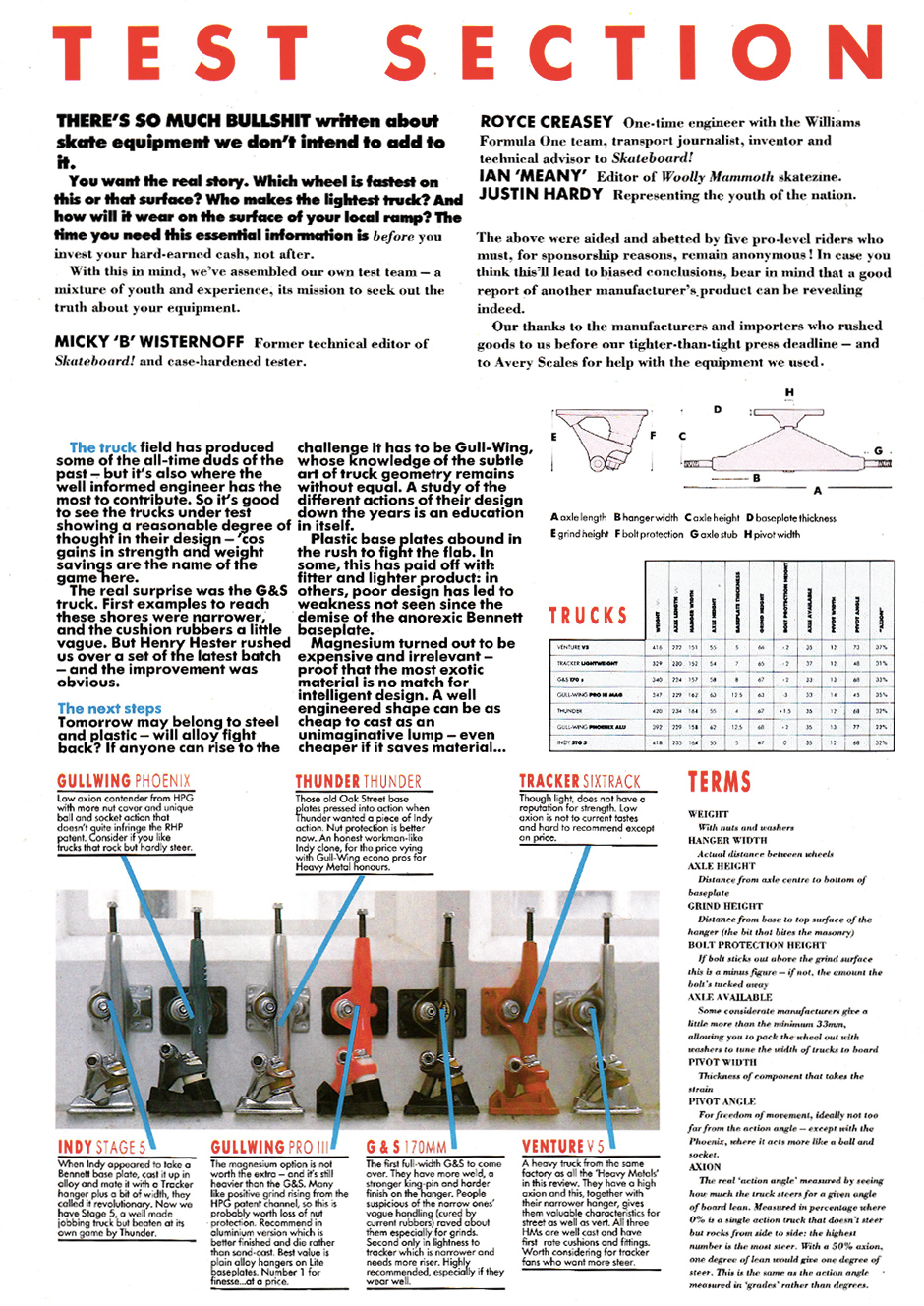

It wasn’t like Thrasher, it was much more harsh and critical about the scene, and it saw itself as an underground magazine, but well produced

It wasn’t like Thrasher, it was much more harsh and critical about the scene, and it saw itself as an underground magazine, but well produced, which is why I always thought the second phase of Skateboard! magazine should be like a zine, but with really nice pictures and really nice layouts. That first phase with Mark Williams as the publisher was like that, then when it got bought by the Nobles and went to Dorset it was much more crap on that side of things, but it wasn’t their fault. The Nobles weren’t very switched on and they had crap desktop publishing software. At the very beginning of the second phase it was still being done with wax and paper and paste-up; it was in the last phase that it was full electronic publishing, but because of that the first phase quality was impeccable. It was beautiful.

Chris Miller Interview in issue one. Photo: J. Grant Brittain

What did you do for the years in between the two versions of the magazine?

I spent seven years doing a lot of Buddhist meditation, insight meditation, Vipassanā. It’s no different to drugs, meditation. You do this thing to your head and it changes your brain chemistry so you can ‘be happy’. But it’s still a neurochemical, it’s not enlightenment. You’re not in touch with the whole of creation, it just feels like it, and you don’t suddenly know more than a guy who’s sat in a field watching his sheep for his whole life.

My meditation is walking in the forest. I see wolves quite often. When you see a wolf, it must be like Palaeolithic man saw wolves. There’s something that happens in your mind, and it’s not like seeing a dog at all. It’s really important to me to be different to how I was three years ago, or five years ago or twenty years ago.

If I have a principal, it’s that if I see something interesting, I go towards it. It’s the question of whether or not the thing is ‘primary reality’. You need primary reality, actually experiencing, doing, touching the thing whether you’re any good at it or not. You’re not reading about it, you’re not hearing about it from somebody else—secondary reality—you’re doing it. You need lots of primary reality. You need to actually go out and do the fucking thing. Even if you discover that it’s a load of shit, it’s important that you learn that it’s a load of shit.

The people doing that are the ones changing the world, not the fucking politicians. The guy working in an office block who keeps his door open after he’s meant to shut for the day so he can help people, the guy with a skate shop opening early on a Saturday morning even though there’s only going to be one customer… The difference things like that make are what changes the world.

The guy working in an office block who keeps his door open after he’s meant to shut for the day so he can help people, the guy with a skate shop opening early on a Saturday morning even though there’s only going to be one customer… The difference things like that make are what changes the world

The timing of the introduction of the second version of Skateboard! was pretty good.

I realised that skateboarding was coming back quite a long time before the magazine would appear, maybe three or four years, when I came across Squeeze—who later did the layout for a while—and Spex and people like that so I started to hassle them, gently, to open up the magazine again.

In the meantime I’d got this job selling computers, and been to the island of Madeira where I met my current wife, and when I got home, after a couple of years doing that, I got really pissed off with the selling computers job and chucked it in just as my future wife was coming to join me from Portugal. It was a huge risk, and on the day she arrived there I chucked my job in, which was pretty tough for her, but then the day after I got the call from Bruce to say they were going to go for it in the Spring.

Even better timing.

Well what he wanted to do was what they call a ‘one shot’, just a single issue to try and cash in on whatever market was there, but I said I’d only do it if we do it as ‘issue one’.

Still, they put this woman in on top of me who edited Looks magazine, which was a magazine about make-up for teenage girls, and that first issue was grim but I just wanted to get it out, just to put a stake in the ground, you know? It wasn’t a thing that any of us were proud of but it was there. Felix had said that the circulation wouldn’t be big enough for his huge company to deal with, so he told Bruce that he had to try to sell it to another publisher. Now, Bruce didn’t tell me about this. He was usually a diamond guy but he’d got a coke habit and he’d broken up from his wife and he was a creep then. Very disappointing.

The only person I knew who published magazines in the right spirit was Mark Williams, with his motorbike magazines. He was a good guy; he’d written for the NME but he was an underground guy. He’d been offered the job of editing the NME but he was caught in a coke bust the week before so he didn’t get it. He was great writer, Mark Williams.

So I call him up, say what the situation is, and we negotiate, and he arranges to buy the title. Then I go into work, just before the first issue is out, and Bruce says, “Steve, I’m afraid we’ve sold the title. I expect if you contact them they might have some kind of job for you but they’re got their own team”, and I said, “It’s alright Bruce you arsehole, I knew you were going to do this, so that’s actually me. I fixed this up”.

So then we were able to start doing it properly. Mark understood what we were trying to do. He didn’t know shit about skateboarding but he understood about the whole spirit of the thing, and we were able to get a good team together, Meany [Ian Lawton] and various other people like that who were doing zines at the time, because I was totally out of contact with the world outside Bristol. By about issue four or five we had something that I think we could be proud of.

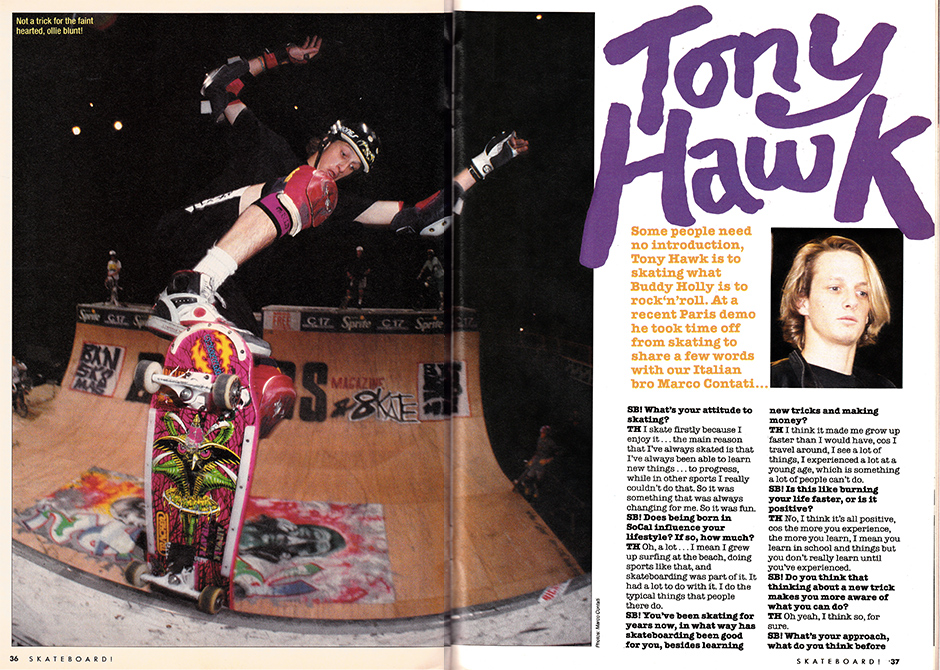

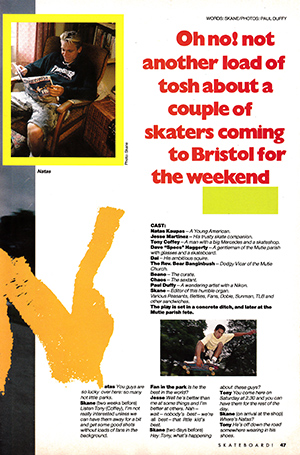

setting the bar high with a Tony Hawk interview in 1989. Photos: Marco Contati. Inset below right – Natas reading issue one in Skane’s flat

I’d say it was before that, really. Issue one had a Chris Miller interview with Grant Brittain pictures. The second one had Natas and Eric Dressen.

Haha! We set our bar really high. We felt tremendous hostility at the start from skaters who felt they’d been there all along, and that RaD had been there for them, and here’s Skane coming back to cash in. And from the American manufacturers too, who were used to saying, “You’ve got to buy this, it’s selling like hot cakes!”, and then we would review it and say, “Well actually this is a load of crap, it’s exactly the same as the old board but with different ink on it” so they’d then be stuck with it, so they really hated us.

Haha! We set our bar really high. We felt tremendous hostility at the start from skaters who felt they’d been there all along, and that RaD had been there for them, and here’s Skane coming back to cash in. And from the American manufacturers too, who were used to saying, “You’ve got to buy this, it’s selling like hot cakes!”, and then we would review it and say, “Well actually this is a load of crap, it’s exactly the same as the old board but with different ink on it” so they’d then be stuck with it, so they really hated us.

I had to build this persona of Skane the editor who was a bastard, and if anybody gave me shit I was going to give them shit back. There was a memorable occasion where we took Sean Goff and Ged Wells to Bristol, as a gesture of trying to get involved with that group of people, and we’d arranged to do a photoshoot at the back of these squats in Totterdown, and these people were proper squat punks. Real squat punks, not trust fund kids, and they had a pretty good miniramp there. Sean Goff and Ged Wells in particular were straight edge, they didn’t drink or smoke or anything, but we’d brought a crate of beer for the squat punks, because squat punks drink beer.

So we’re handing the beers round, and Ged takes one and just smashes it on the ground. And there were little kids there, you know? So I put them straight in the van and drove them to the train station, and gave them hell on the way. I’d bought the beer for the people who let us skate their ramp, and he smashed one in front of them?! I gave him hell and after that there was none of that shit. I think Sean played the grown-up then, he’s turned into a real ambassador for the art. I’d get phone calls in the middle of the night, these mockney accents saying, “People don’t like you”, and it’d just be “OK, fine, you’ve said your bit and impressed the friends I can hear in the background. Now fuck off”. Haha!

Back before you could use social media to be a dick to people.

I remember an importer sent us a load of boards to review, and of course our reviewing involved handing them out to kids and saying, “Skate this until it’s dead, and then we’ll look at it”, and he phoned up to get his decks back! I told him he couldn’t sell them because they’d been ridden and he thought I was on coke or something, because he always was… I’m a manic depressive; when I’ve got the wind in my sails there’s no stopping me, but I had to manage producing the mag around that. If I was down I had to make arrangements to work in a way I could cope with it, like taking a trip out to the country or taking pictures of product or something.

The key thing was that you had to get the copy in on copy day. The printers printed thousands of magazines, and the machine was like a terrace of houses inside a factory. It was that big. The paper goes in one end and the bound magazines come out the other, and it prints 30,000 magazines in about twenty-five minutes but if you miss that slot you are fucked. You don’t have magazines to deliver to the newsstands, you don’t get the cash back and the whole company goes down because we’re talking serious money to have those printed. Fifteen grand or something like that.

However sketchy people were—and a lot of the people writing for it were serious stoners or whatever—you had to be on it. You had to learn who you could trust and I could trust Skate Muties to paste up their own copy and deliver it to the printers, and they’d sometimes be responsible for three or four pages, so that’s a lot of blank space if they don’t get it there on time.

One time Paul Duffy got stuck in Paris—he met a girl and got wasted—and Mark Williams had to go down and meet him off the train at some ungodly hour to get his rolls of film off him and to the lab to get processed, otherwise we wouldn’t have an article. I always had an article in my back pocket, an extra one which could go in the next issue, and we’d improvise a lot. It was on a wing and a prayer a lot. We didn’t really have an office, it was half of my living room in my one-bed flat in Bristol but it’d often be filled with skaters. Natas was there after a photoshoot one time, having a cup of tea.

I don’t imagine you were ever starstruck around skateboarders.

I was never starstruck about skaters, even first time round when I was meeting Stacy Peralta and people like that. They’re amazing skaters and all that, but they’re just guys.

You must be the only person I’ve known to say something negative about Mark Gonzales.

You must be the only person I’ve known to say something negative about Mark Gonzales.

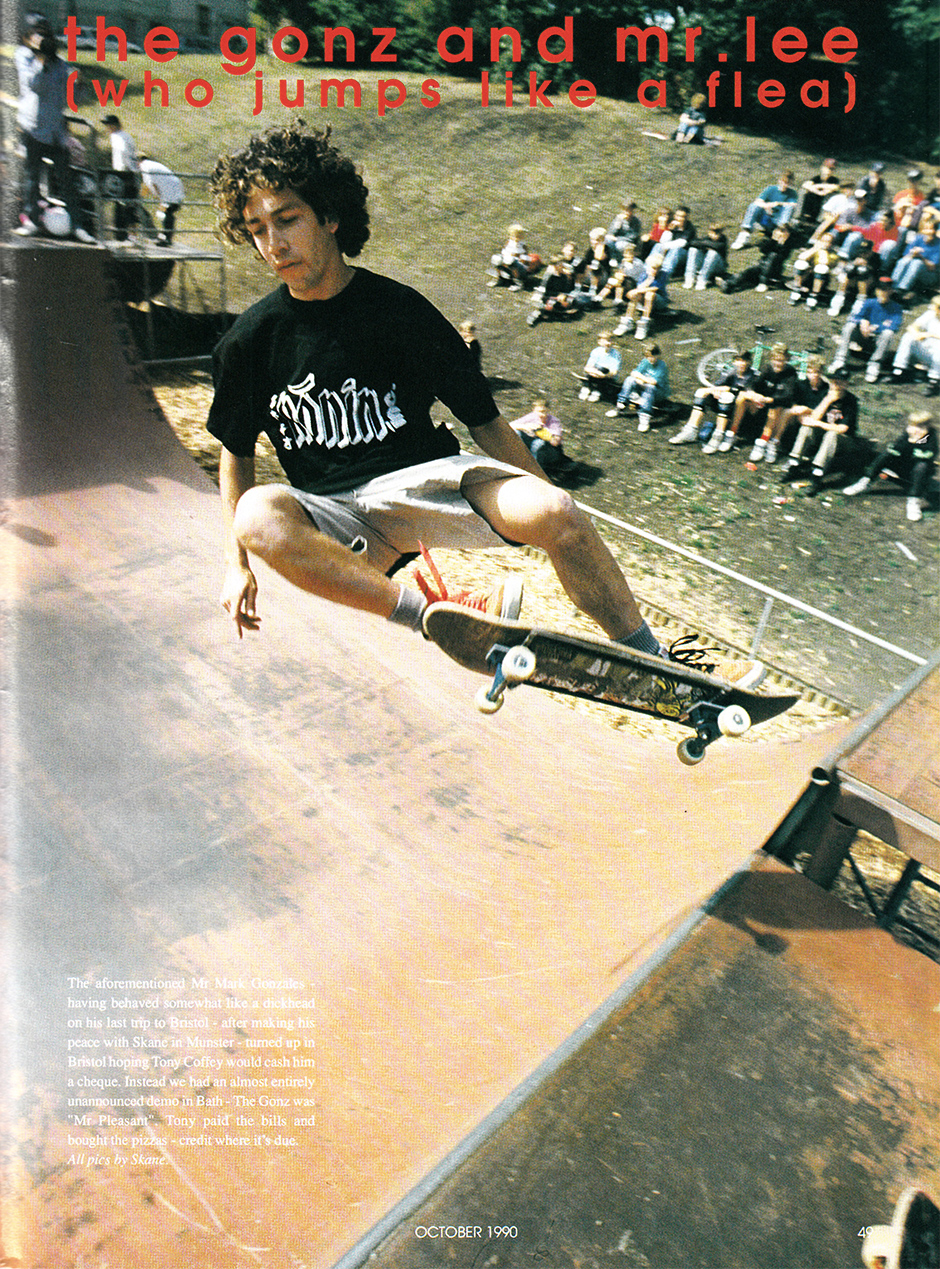

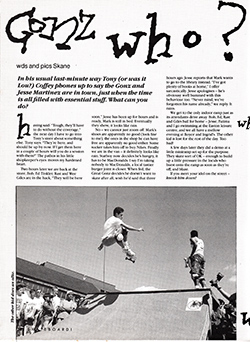

Tony Coffey, who owned the skate shop in Bristol, was the importer for Rocco, I think, and he rang me up one morning to tell me they had the Gonz there, and they wanted to get some pictures of him and an interview or something. He hadn’t warned me and I had other things to do, but he persuaded me and I agreed.

So I turn up at his shop and go, “Where’s the fucking Gonz then?”, and he told me how he needed a particular brand of shoes or something, so someone had taken him off to find them. He finally turns up so we drive off to the skatepark in my van, and there are all these kids waiting to see him, and we get down to the bottom, by College Green, and he suddenly says that he doesn’t want to skate. He wants to go to the library and get a book. I told him he should have said earlier, because I’ve got thousands of books at home, and there are kids waiting to see him skate. I just stopped the van there and let him out. He was dissing the kids, that was the key.

So I turn up at his shop and go, “Where’s the fucking Gonz then?”, and he told me how he needed a particular brand of shoes or something, so someone had taken him off to find them. He finally turns up so we drive off to the skatepark in my van, and there are all these kids waiting to see him, and we get down to the bottom, by College Green, and he suddenly says that he doesn’t want to skate. He wants to go to the library and get a book. I told him he should have said earlier, because I’ve got thousands of books at home, and there are kids waiting to see him skate. I just stopped the van there and let him out. He was dissing the kids, that was the key.

They did end up skating, and there were other guys there as well, so I printed a lot of pictures of them and one of him, but the caption just said ‘Here’s some guy’, and I told the story. That one-inch column of me being so critical to him must have got under his skin because it was on the graphic of his next board.

Then he came back with Jason Lee and we did a session in Bath, and he was sweet as a nut. I remember later on at Münster when I met Grant Brittain for the first time, and I said to him about how I’d had this run-in with Gonz and told me he was just like that sometimes. It was him being him, and me being me, and I think he’s been really cool since, but if that had been an American magazine it’d have been covered up and he’d have been allowed to go to the library and they’d have scheduled the shoot for another day or something. Not here. We take no prisoners! Haha!

Second Gonz visit in 1990 shot by Steve Kane

When Skateboard! came back, in 1988, you guys all knew what you were doing, but it was a different marketplace, and one that already had RaD in it. How were you able to hit the ground running like you did?

We didn’t know shit about what we were doing. I’d seen the actual production side of a magazine first time round, but I’d never edited. Being a contributor is piece of piss; you go somewhere with a photographer, write a little bit about it and hand it in. Hang about the office. Try out some new gear. Piece of piss, and that’s all I wanted to do this time around too, but someone had to do it and get the spirit right. Second time around I realised that if anything went wrong I was going to have to live with it and I really didn’t know how to do it, and I was stuck with this editor who knew about make-up for 13 year-old girls.

We didn’t know shit about what we were doing. I’d seen the actual production side of a magazine first time round, but I’d never edited. Being a contributor is piece of piss; you go somewhere with a photographer, write a little bit about it and hand it in. Hang about the office. Try out some new gear. Piece of piss, and that’s all I wanted to do this time around too, but someone had to do it and get the spirit right. Second time around I realised that if anything went wrong I was going to have to live with it and I really didn’t know how to do it, and I was stuck with this editor who knew about make-up for 13 year-old girls.

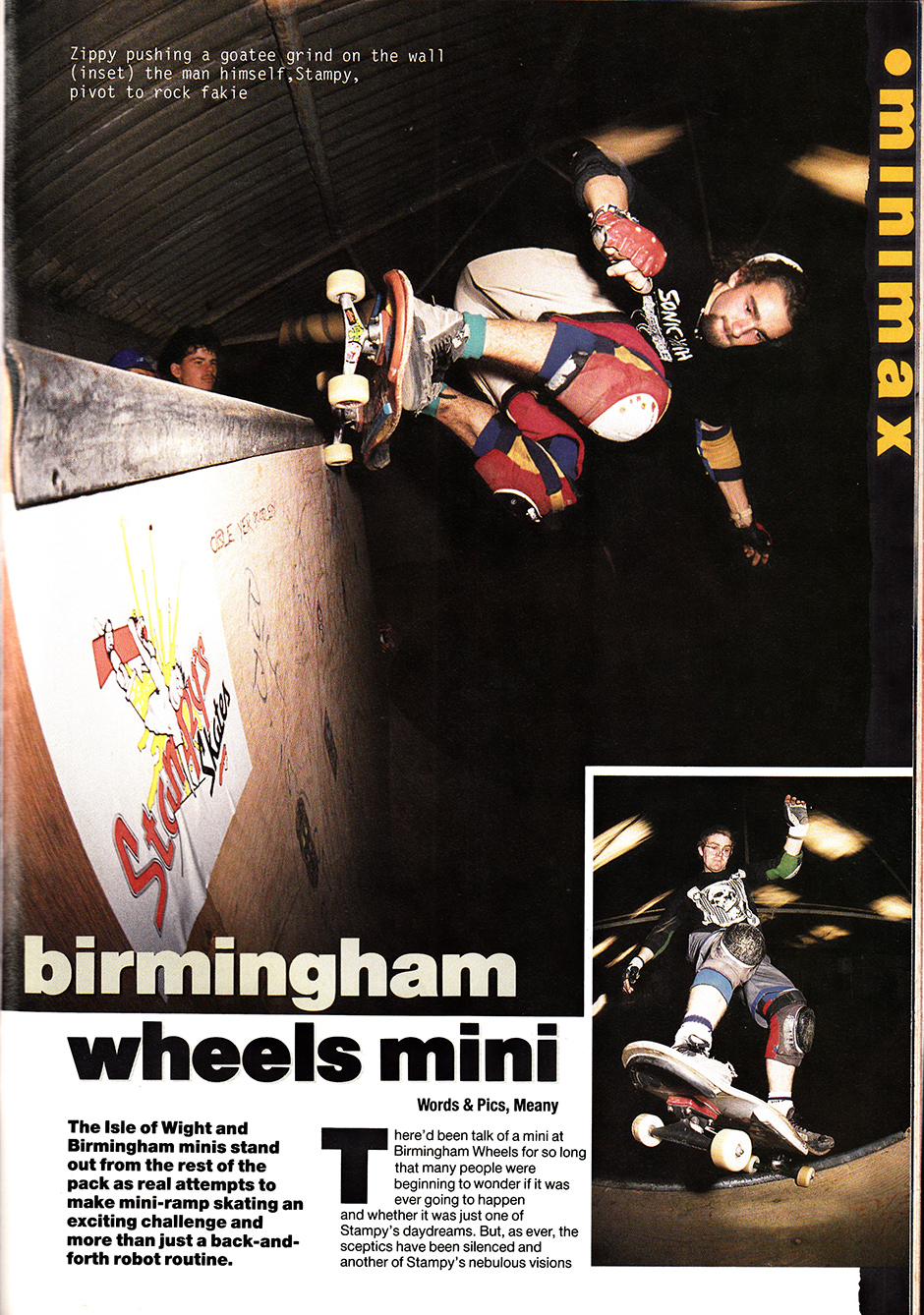

I don’t know if we hit the ground running but we had a very clear idea for what it should be. The first thing we had to accept, was that although it may be written by 18 year-olds, student-age people, it wasn’t for them. I’d always have to stop Meany doing stuff like that, he’d write an article that his friends thought was cool but I had to keep reminding him that he was writing for 13 and 14 year-olds. How old were you at the time?

I was 12 when it started.

Right. Kids have a different way of looking at the world. Students find it hard to write for those people because they’ve only just escaped from that, so I had to find people like the Skate Muties who had managed to avoid growing up. I wanted to hand over the editorship to Meany much earlier because I was getting tired and I was losing interest, but he never had the confidence to get that, and I thought if the magazine didn’t have that, it’d die.

I remember I spoke to TLB [RaD editor Tim Leighton-Boyce], because I knew him from when he worked for Alpine Sports. I spoke to him on the phone to tell him we were doing the magazine, and he was very supportive. We made this pact that he would have the mail order ads, and I would have the product reviews. So you had to read us to find out what was good and what was shit, and then buy his mag in order to buy the stuff. So we carved up and stitched up the market, and by doing that we also stitched up the trade, because they couldn’t play us off against each other. They couldn’t say they were pulling their mail order ads from Skateboard! if we were nasty about them, because we didn’t want them anyway.

So we carved up and stitched up the market, and by doing that we also stitched up the trade, because they couldn’t play us off against each other

There’s a letter from Freestyle BMX editor Mark Noble in an early issue, congratulating you for getting the magazine going again, and your reply tells him to “go back to pushbikes’.

And then his dad ended up owning the magazine! I didn’t want to miss that journalistic opportunity. I don’t know if Mark was offended but I just wanted my readers to see that being said. It was just too good an opportunity! That’s an example of me being a bit manic, I think. I said “Thanks Mark, now you can go back to pushbikes,” pretty fair really.

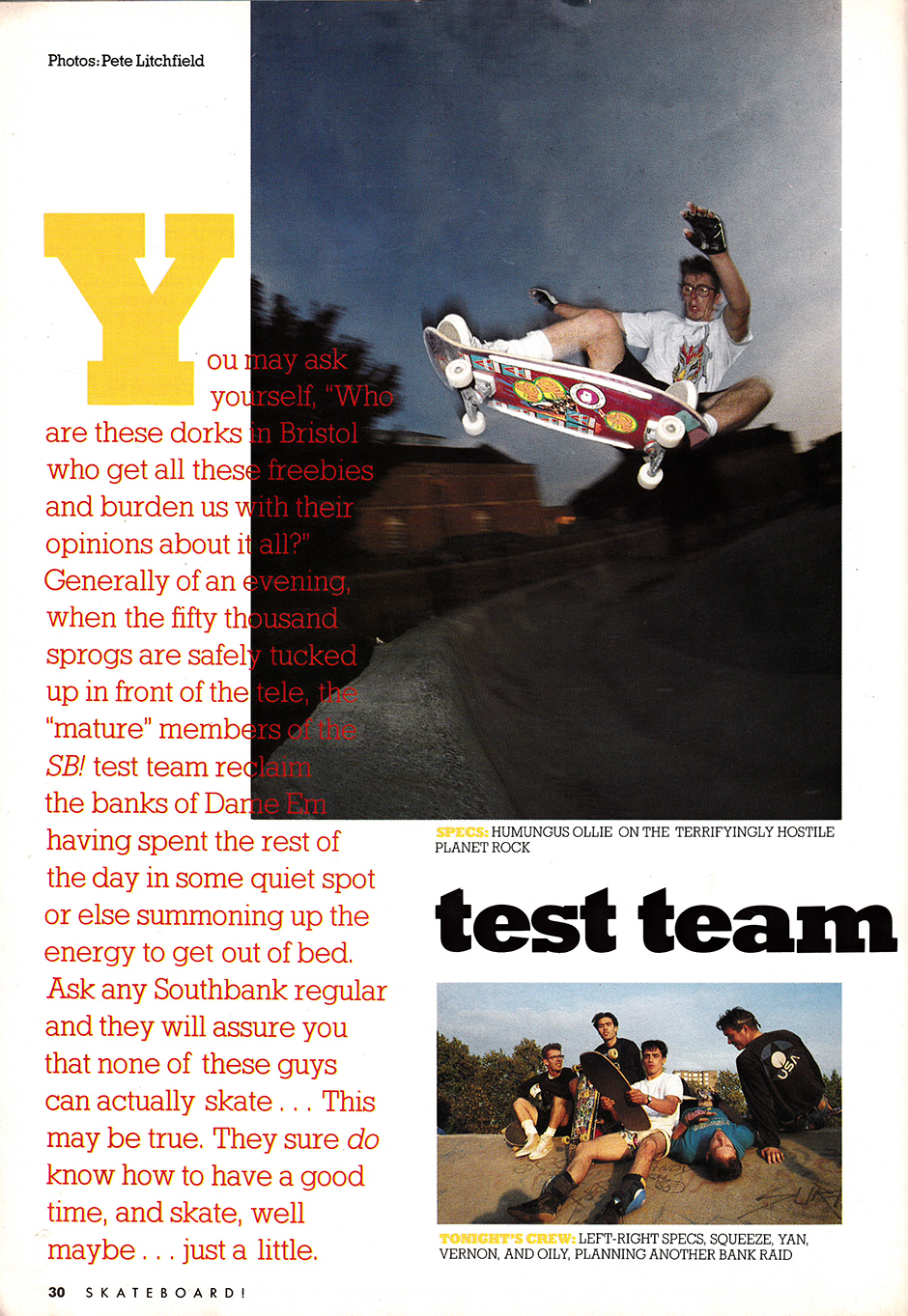

Spex levitates at Planet Rock on a 1998 skateboard! test team outing. Photo: Pete Litchfield

The product pages in Skateboard! were always incredibly in-depth, but what kind of wacky crap did you see? There were a lot of attempts at ‘innovation’ back then.

I really knew that those pages were going to appeal to the 13 and 14 year-olds. There is always that kid who doesn’t give a shit about his stuff and his bearings are all fucked and he’s a great skater anyway, but there were always the other kids who really did care.

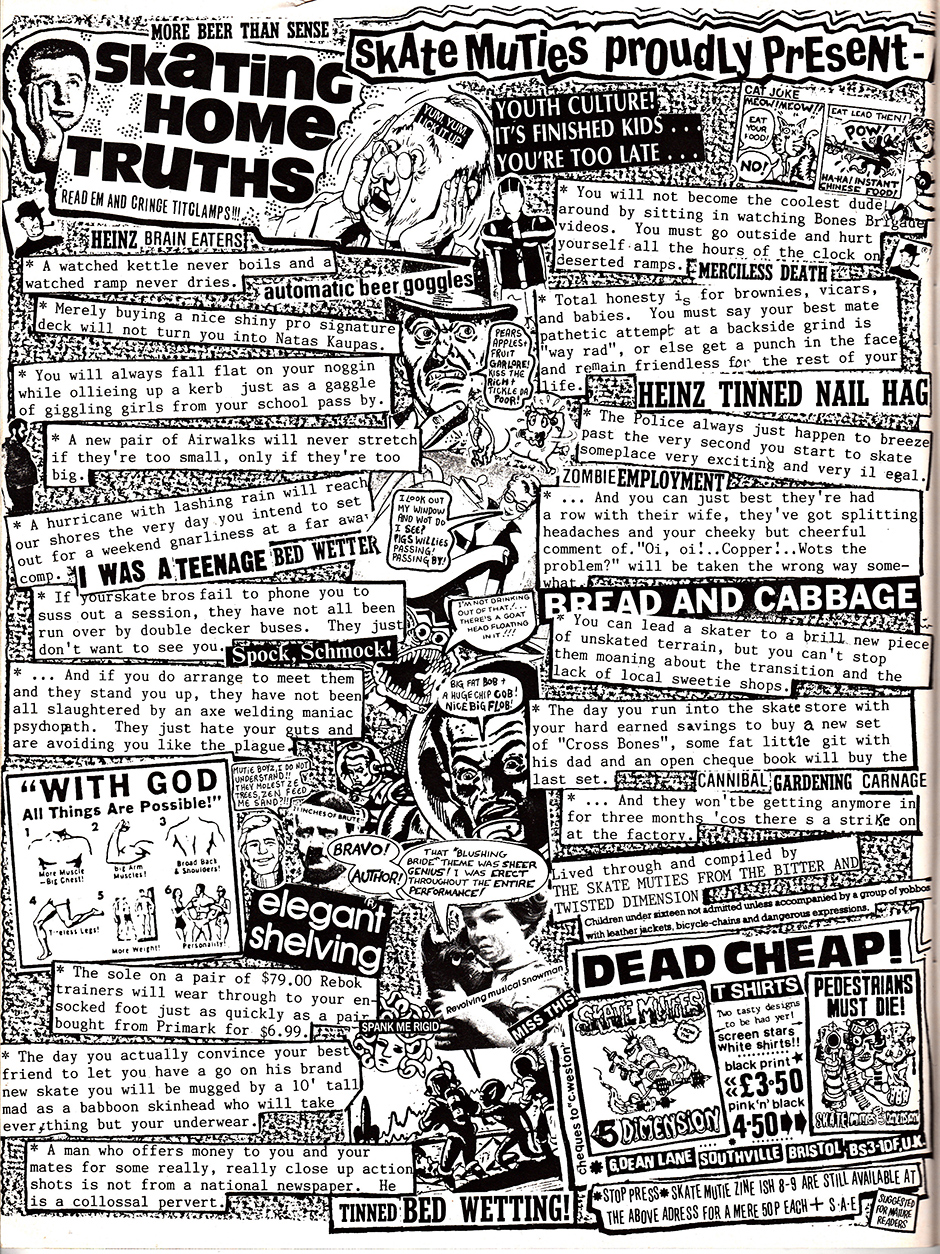

Second time around, there really weren’t too many awful things because I’d been through the 70s when there was some really dreadful shit, so most of the totally stupid things had gone by then. What there was, however, was the big manufacturers fobbing people off with things like wheels that skate really well for a couple of weeks and then got flatspots, and stuff like that, while a lot of the small manufacturers were much better for that.

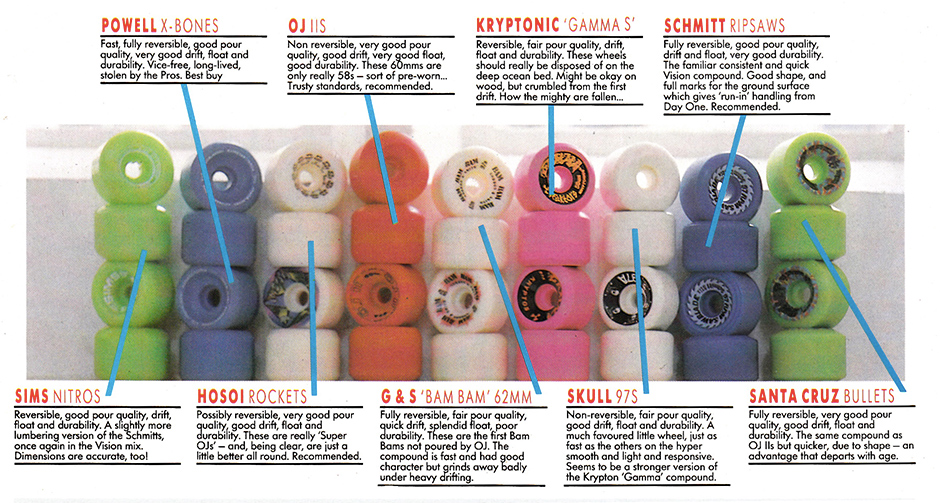

American product was generally made for perfect marble-like surfaces so it could often be very hard and not very resilient for most European skaters who are skating on not-quite-as-good surfaces, and we started to recognise different compounds and stuff like that, and we started to understand how trucks worked, and were able to explain the different geometries of trucks to the readers as we were discovering them ourselves.

The most memorable thing was when the American guys who made the stuff started to read the magazine and be really pleased that we noticed what they were getting right, their bosses often didn’t. A couple of years into it we started getting feedback from people like Gullwing, from the people who actually did the work there, and they could take the magazine to their bosses and show them what was working and what wasn’t.

I’d always tell the little shops if something was going to get a bad review, so they’d know not to order it. I didn’t mind screwing Shiner, but I didn’t want some little shop in Loughborough stuck with twenty boards they can’t sell.

Simultaneously you’re showing your readers how to make most of this stuff themselves. How important was that to you?

That was really, really important. De-mystifying it. I was really hard to make trucks, so we could only advise on how to modify them, and you can’t make wheels, but just about everything else. It was about not being passive. I did an article called ‘How to Con Your Council Into Building You a Park’,

That was really, really important. De-mystifying it. I was really hard to make trucks, so we could only advise on how to modify them, and you can’t make wheels, but just about everything else. It was about not being passive. I did an article called ‘How to Con Your Council Into Building You a Park’,  with all the instructions on how to make sure they don’t fuck it. That was politics, and I’d been doing politics before so I knew these kind of people, and I wanted you 13 and 14 year-olds to understand that you are able to understand local politicians and get what makes them tick, because that would be useful in later life, shall we say.

with all the instructions on how to make sure they don’t fuck it. That was politics, and I’d been doing politics before so I knew these kind of people, and I wanted you 13 and 14 year-olds to understand that you are able to understand local politicians and get what makes them tick, because that would be useful in later life, shall we say.

The same with the science too, that was always so interesting to me. At parties I’d much rather talk to the guy on his own who knows all about the different types of telegraph poles or whatever, than the people talking about how much their house is worth. I just prefer people who are really enthusiastic about something, and I like to be that person too.

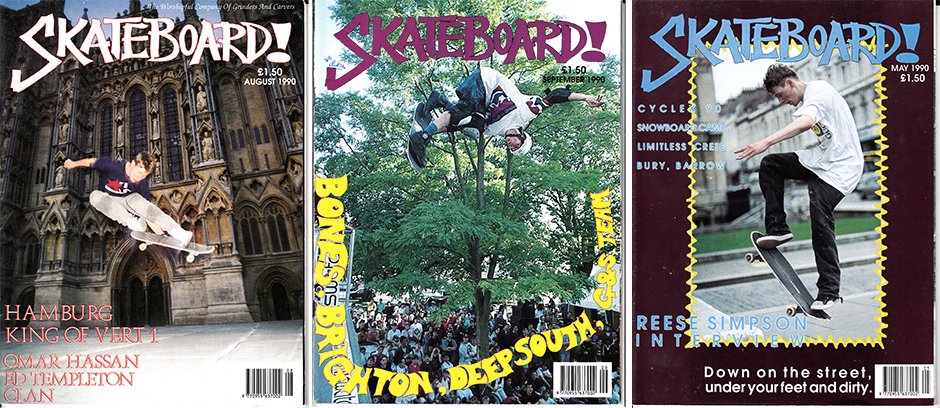

You said in 1988 that street skaters were getting so good that nobody would care about parks soon. That was quite prescient.

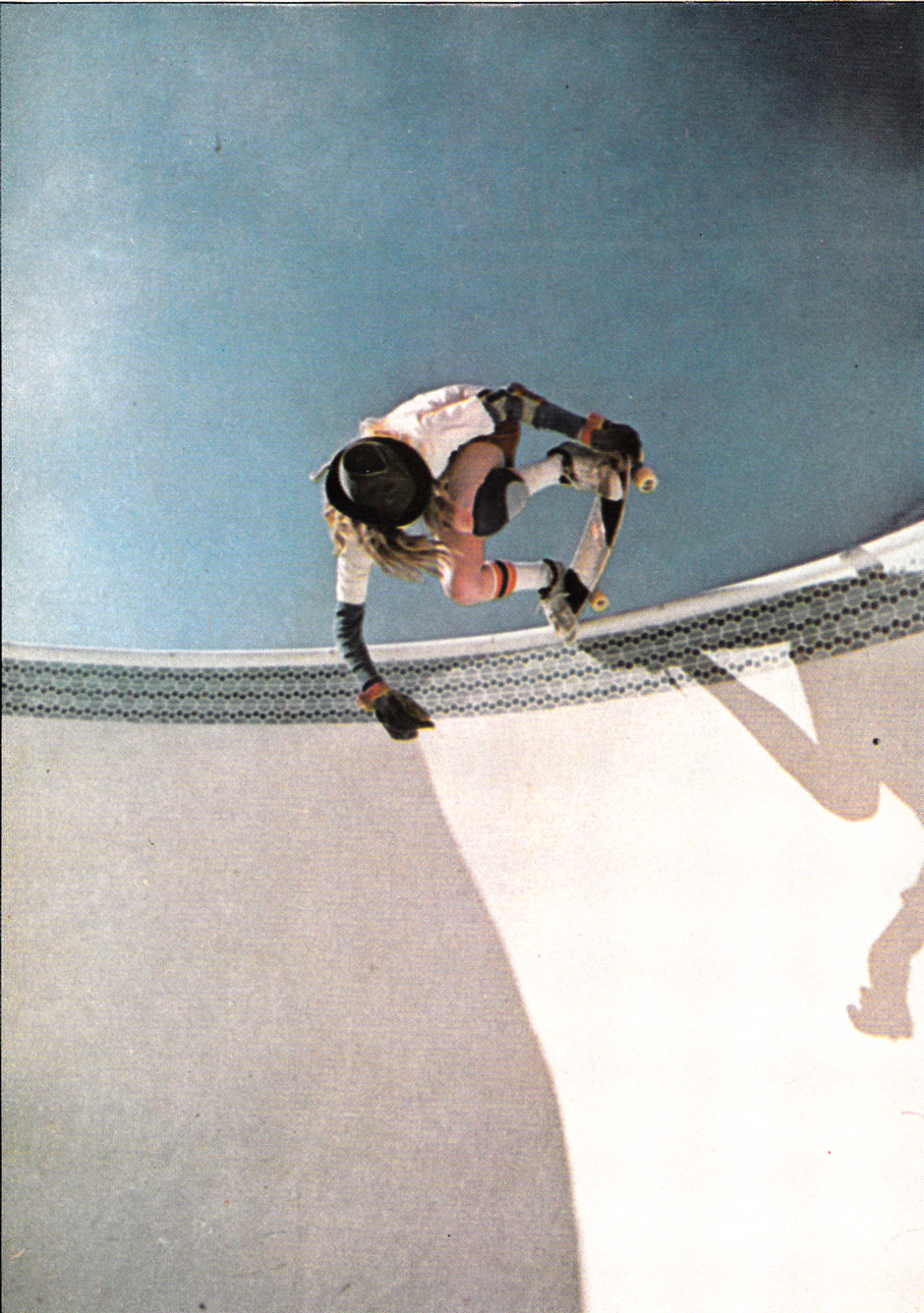

There were a crucial three issues, where the covers broadcast my message, I suppose. Particularly Rodney Mullen in front of the Wells Cathedral; he was doing this really rad trick, from a standstill because the surface was hellish. There was no movement there, which I didn’t really approve of but I fully respected it. He’s a lovely guy. Then the next issue was Tony Hawk doing an air against a background of trees, and that felt like skateboarding that had ‘been’. Then the next cover was this kid who was totally unknown and had only been skating for four or five months, skating this stone block in Bristol, because that’s what the kids were skating.

Three crucial covers. Rodney Mullen. Tony Hawk shot by Skane himself and the controversial Bristol street shot

I got real stick for putting that on the cover, with people saying it looked ugly and it wasn’t real skateboarding but I knew skateboarding was going into a phase where it was like that, whether I liked it or not. But that’s where it was going and if kids kept doing that stuff, that’d carry it through. It got better when younger skaters started using the whole street, but that was yet to come. People like Gonz and Natas and Dressen were already showing what you could really do.

That was more accessible and interesting to a 13 year-old than some 30 year-old skating a perfect ramp in California. The end of stadium-rock skateboarding had to come.

Haha! It was different in Brazil, because they had so many concrete parks.

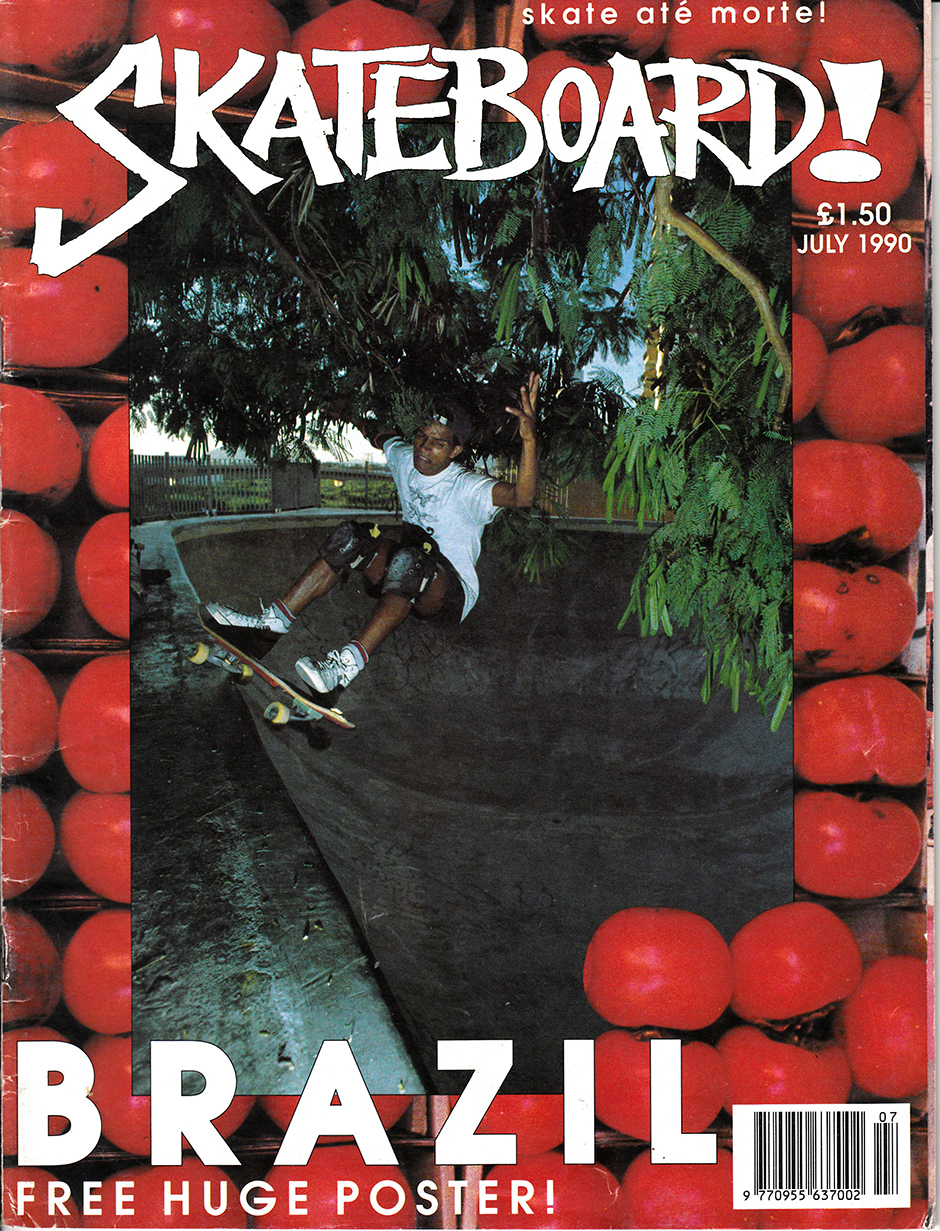

That Brazil issue was pretty eye-opening for back then. How did you manage to get there?

Jorge Kuge, who was the head of Urgh! Skates—which was the main Brazil-based skateboard company and they actually made all of their own equipment in Brazil, trucks and everything—phoned me up one day in the office to ask if I wanted to go to Brazil. I told him that of course I wanted to go to Brazil, so he said that if I made my way there he’d cover everything once I got there. I said that when we went on trips we always took skaters with us, but relative unknowns. Thrasher would always take the top stars there, and they’d do demos, and the Brazilians would just have to sit and watch. It was so wrong. So I phoned Neil Danns, Davie Phillips and Pete Dossett, but Pete didn’t want to go. He skated for Death Box, and said, “Don’t tell Jeremy [Fox], he’ll make me go!”, so I said “Fine, someone else can go” so Pike came instead.

a Brazilian by the name of Come Rato (‘Eats Rats’-English translation) Grinds the pool in Barramares. Photo: Steve Kane

When we arrived Jorge had this full ten-day schedule worked out, which didn’t favour his company or his skaters at all. It was a complete riot, we went absolutely everywhere non-stop and I took about 1,000 slides on that trip. It was great because we didn’t know anything about Brazil; we had this idea from the press that it was a third-world country where everybody was starving or shooting each other, and obviously we didn’t know anything about their skateboarding lives and we found out that it’s an incredibly complicated culture. We’d be in places where you weren’t supposed to go because it was so violent or whatever, and any visitors were either going to come out naked or dead, and we’d be there as skaters getting no trouble at all!

We went to this guy’s ranch—his dad was a coke dealer—and he had his own personal park and a pet lion, but on the other side, we met kids who didn’t just share a skateboard, they shared a pair of flip-flops to skate in

We went to this guy’s ranch—his dad was a coke dealer—and he had his own personal park and a pet lion, but on the other side, we met kids who didn’t just share a skateboard, they shared a pair of flip-flops to skate in. There’s a tremendous divide. Neil loved it, Davie was completely at home but Pike was just freaked out. It was a terrible culture shock for him.

It was a culture shock for a 13 or 14 year-old kid too. It was pretty far from anything you’d expect to see in a British skateboard magazine, but it was a lesson in Brazilian culture that not many people, let alone 13 year-olds, were privy to.

The context of a photo has always been really important to me, I’d always want to show the surroundings and the buildings and architecture in the background, and that really paid off in Brazil. You really got the feeling of being there, and of how different it was. It’s not just photos of skateboarders doing tricks. Like a skatepark wedged in between some huge buildings, and then on the other hand there’s the beach, the Copacobana. It was amazing. Unbelievable.

In the centrefold we had Diego Menezes, who was 12 at the time, pulling these crazy tweaked tricks over the hip. I think it was about four years later he won his first international championship comp.

Talking of travel, you had a lot of contacts across the UK. A lot of correspondents.

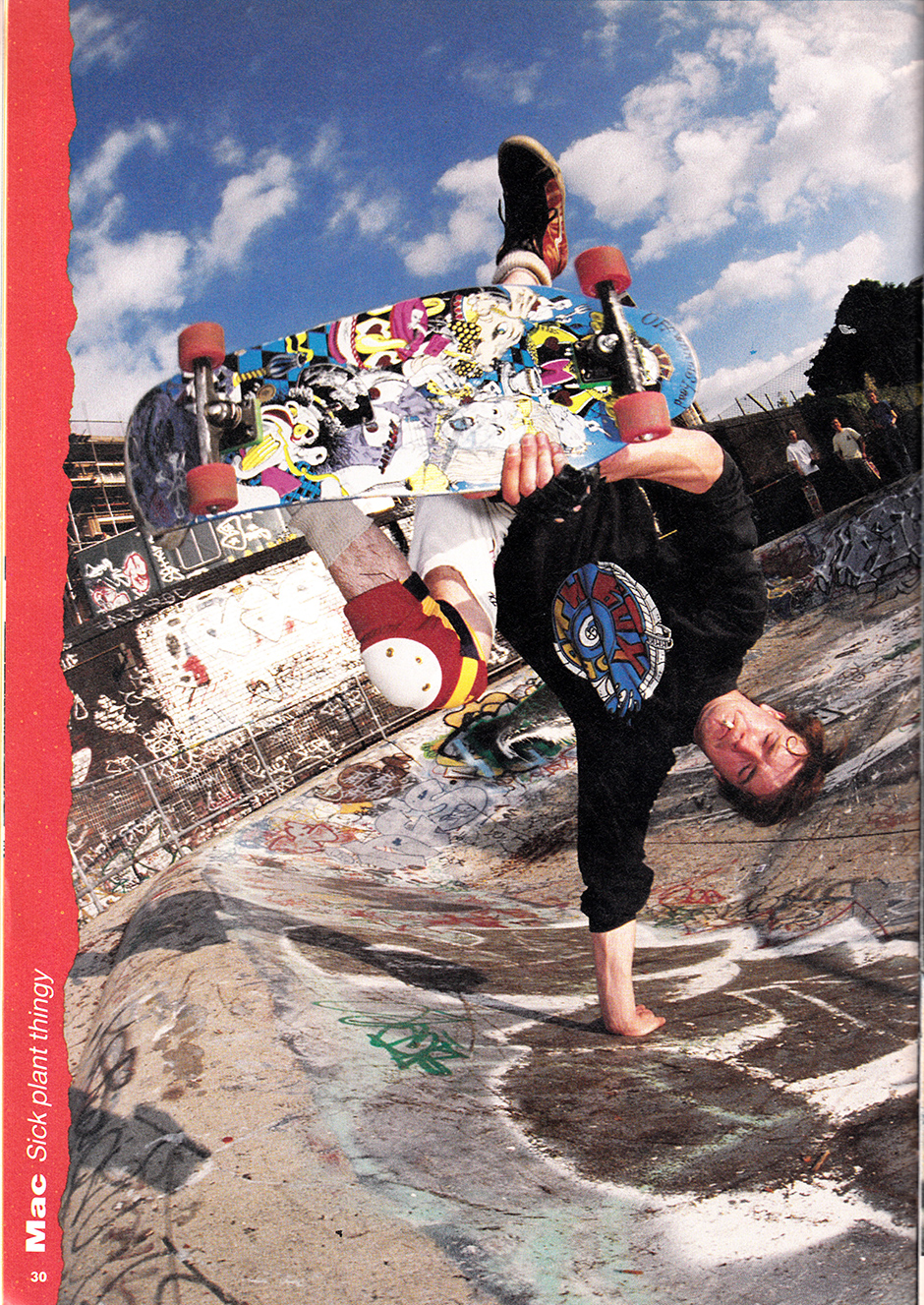

I didn’t travel much but I gave Meany everything north of The Wash, because he lived in Birmingham, but there were other people dotted about. If we did trips we concentrated on Europe, and would fill a van with people like sardines. We’d pull up somewhere, open the van, and all these people would pour out, like something from the Keystone Cops. We’d drive for twenty-four hours sometimes. It was always madness. We wouldn’t take famous skateboarders, we’d just take the magazine team, who were good but they weren’t ‘famous’. Somebody like Mac, who was this crazy, punk-rock Scottish guy who dressed like he’d just come out the pub, with a Skateboard! t-shirt under his old suit jacket. He was a miserable bastard but he was great.

an inverted Mac ruling in 1989. Photo: ‘Mad’ Mike John

Everybody else was heading to mainland Europe to steal tracksuits and glass the locals back then, and there’s you with a van full of skateboarders.

Haha! I wasn’t following what anyone else was doing, but I wanted to show kids that they could do it. They could get an Interrail ticket, turn up at anywhere in Europe with a skateboard in hand, meet new skateboarders and you’d belong. You didn’t need anything else.

I don’t know what it’s like now, but you could go to anywhere in Europe and find maybe all six local skateboarders, and you were like brothers. The new person arriving would usually spot something to skate that the locals hadn’t, too.

you could go to anywhere in Europe and find maybe all six local skateboarders, and you were like brothers

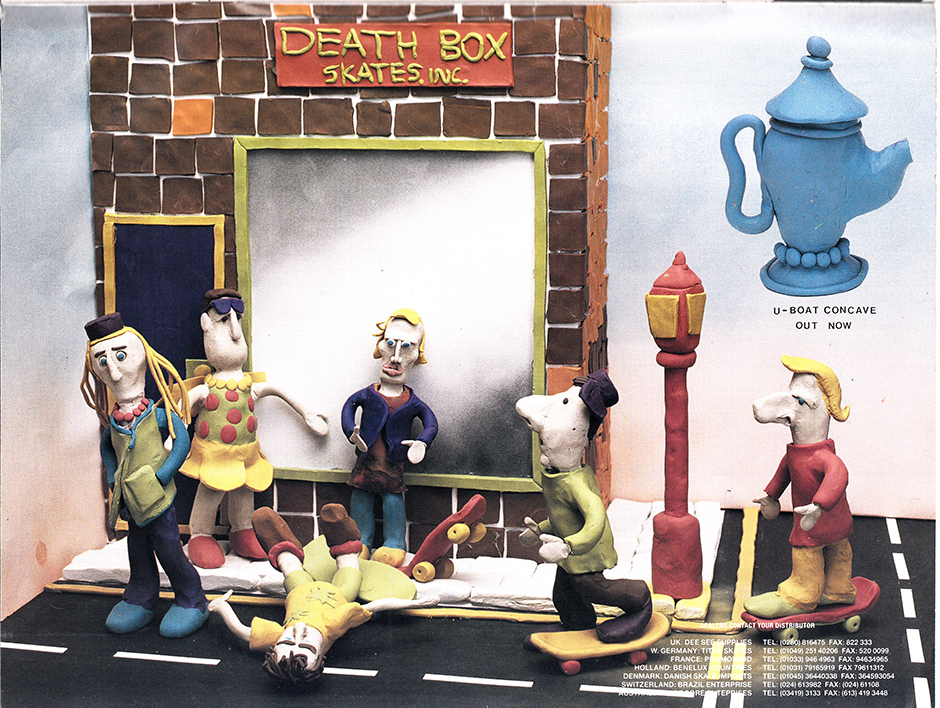

You mentioned Mac there. The graphics he did for Death Box were really good.

Mac did wonderful stuff for them, graphically. He was always taking the piss out of the skater whose board he was designing. He had this ongoing thing with Wurzel and hippies, because Wurzel had a hippy mum, and there was always a bit of tension between him and Mac.

What other magazines were you looking at, when you were doing Skateboard! magazine?

I’d maybe thumb through Thrasher if I thought there was something interesting in it, but we didn’t look at any other magazines. When they started to do a product page, it was pathetic. It wasn’t my job to know what the other magazines were doing. I know in sales or something, you need to spend all your time looking at what your competitors are doing, but I didn’t look at anything. We’d always be purely focused on what we were going to do next month.

What about non-skate mags? Music magazines of the time were getting interesting.

Fuck all. I didn’t have the space. I didn’t know what music was happening or anything, because I’d only ever hear music in the car. About a year after I finished at Skateboard! I had a breakdown and I had this Nirvana song stuck in my mind, “No I don’t have a gun” going round and round in my head as they took me off to the funny farm but I didn’t know who Nirvana were. I didn’t know that Massive Attack were becoming successful. I was completely out of touch with everything except for skateboarding, because that required complete obsession. I wasn’t aware of anything else but I was completely aware of skateboarding, on all levels.

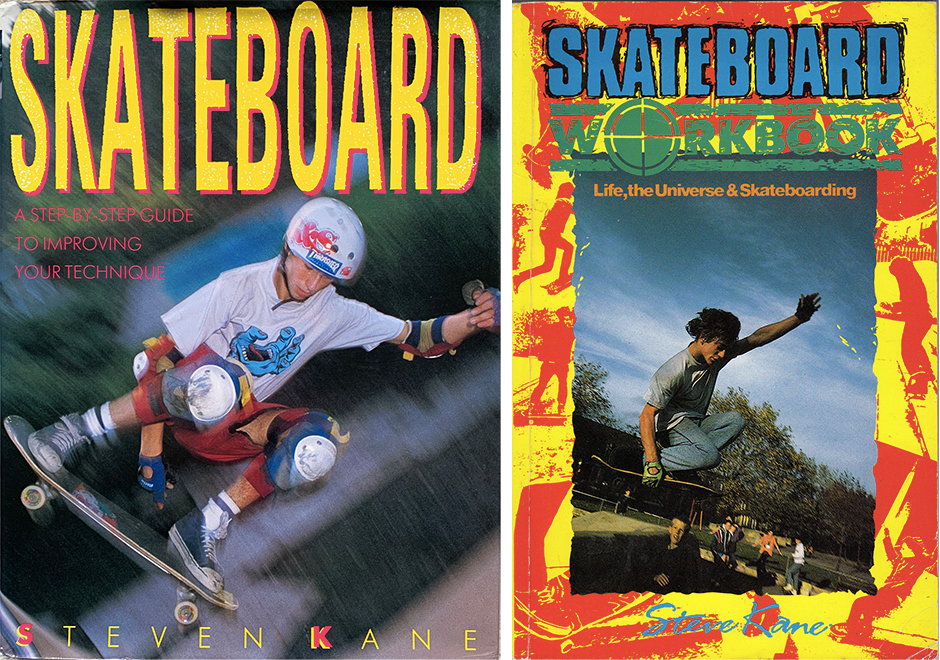

Two more publications penned by Steve Kane from 1989

The music pages in Skateboard! were really good. I got into a lot of stuff through those that would have taken me years to discover otherwise.

It was most Meany and Bear Hackenbush [Mike Hopewell] that did that. One thing I did realise, musically, was the there was this whole area of music that was really interesting and dangerous, kind of like we were, and those two covered it really well, with their somewhat-cryptic reviews, which sometimes made me hoot. Meany was much more into music than skateboarding, and things like that were why I couldn’t continue with the magazine. You had to be 100% obsessed about skateboarding.

When you did leave, there were a couple of gaps in issues. It skipped a couple of months. What happened there?

The company who published it, the Nobles, went bankrupt. And they owed me serious money. The guy who was in charge… Well, when you subscribe to National Geographic, you get a certificate saying you’re a member of the National Geographic Society, and he had his framed on his wall because he didn’t have anything else to be proud of… One time when I went into his office to chase up some money he told me he was a judo blackbelt. It’s not like I’d gone in there to threaten him with violence, I just wanted my fucking money!

Every asset including the title itself belonged to the creditors, of which I was a major one, but he’d passed all that on to one of the guys who did one of the crap magazines they published and I’ve never fully forgiven him for that. I knew he’d put his house up for security with two different printers, one of whom was local to him, in Dorchester, and the other one was in Bristol. I knew the Bristol one so I called them up to tell them that Peter Noble was conning them, and he’d put his house up for security with another printer too, because he couldn’t afford to pay them. This guy called the other printers, and they both closed him down the next day.

I’d forced Peter Noble to make me an employee, which meant I got unemployment insurance when they went down, which meant I could collect the credit insurance on my car and I could get unemployment money without any hassle. Which was basically the money I was owed, for the Brazil trip and all the other stuff I’d put on my credit card. That all got paid off, but I was fucked and I had a serious breakdown not long after that, and I haven’t worked since.

I was completely out of touch with everything except for skateboarding, because that required complete obsession. I wasn’t aware of anything else but I was completely aware of skateboarding, on all levels

Did you look at the magazine after you’d left? Were you interested in what those guys were doing?

Nah. It was important to me not to give a fuck. Otherwise I’d have been even more upset. It was a horrible loss for me. It’s one thing to have it passed on to somebody else, but to have it happen like that was sickening. The skateboarders themselves and all the skater-owned companies were all sweet as a nut, but the industry hated me.

Were you too early with Snowboard! magazine? I feel like if you’d waited another year or so to launch that, it’d have been a lot bigger.

Were you too early with Snowboard! magazine? I feel like if you’d waited another year or so to launch that, it’d have been a lot bigger.

No. No, no, no. Snowboard! magazine didn’t survive, but the group of people we put together to do it went and did Snowboard UK, which was essentially the same magazine under a different name.

I’d found this group of snowboarders who’d never done a magazine before, helped them get started and we gave it away with our magazine, to show people that you can do this. ‘You can do this too, now fuck off and do it!’

Was Benji Boards paid for with Pink Floyd money? That’s the rumour.

I don’t know about that, but I do know there was a hell of a lot of coke about. Ben went down because towards the end he was driving around—I think it was a Jag he had—and the police stopped him. He gave them lip so they turned him over and found a lot of coke in his car. He was a petty criminal already anyway, I think.

I don’t know about the Pink Floyd thing, but it sounds like something he’d have put about, just for bragging rights. It’s more likely that it was the product of his criminal practices. There were quite a lot of skateboard businesses that were laundering drug money at that time.

You knew Jeremy Henderson. What can you tell me about him?

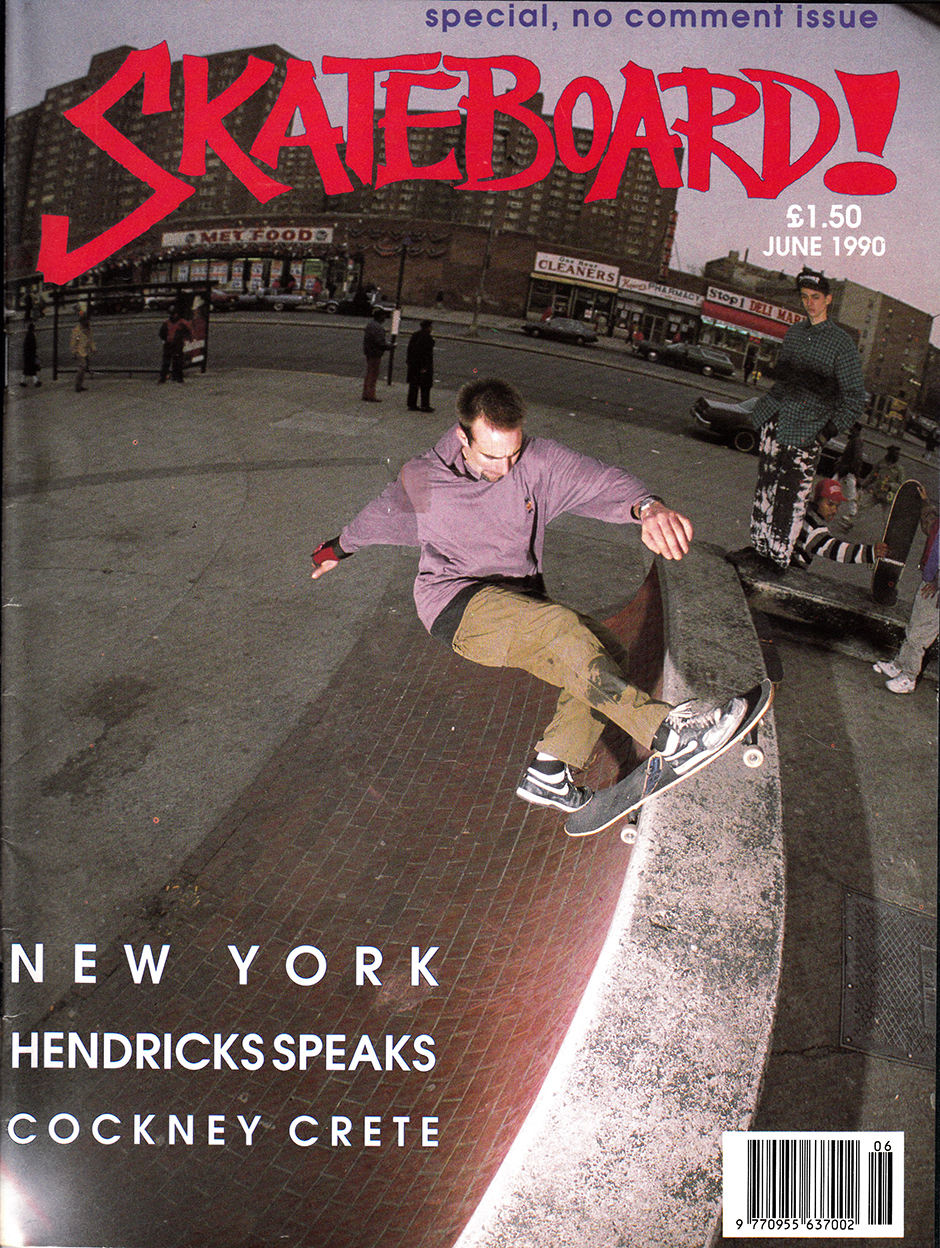

I don’t know him that well, but he’s a very sweet guy. He was quiet, and didn’t have any bullshit. He was street skating in New York when we did the second phase of the magazine, and he was friends with Shawn Stüssy and the Shut Skates people. He was also good friends with Eric Dressen, which is why he was over here.

the godfather of NY street skating Jeremy Henderson front rocks in Harlem. Photo: Marco Contati

I was talking to John Sablosky not long ago, and Sablosky had lost touch with him but somebody else told me Jeremy Henderson had had a terrible surfing accident about four years ago, and it looked like he was going to be paralysed—which was especially awful because his brother was already paralysed—but he was really lucky and he got better. He doesn’t skate anymore but he’s a keen surfer. He was a really good skater, but he was just a really nice guy.

Jeremy had a lot to do with the progression of New York street skating, early on.

Definitely. A funny thing about Shut Skates in fact, is that they were called Shut Skates because they were always shut! The guys who owned it were always away out skateboarding. Haha!

Shawn Stüssy, who was Jeremy’s friend, his dad was a tailor, they said, so his original clothes were beautifully cut. I had a pair of his shorts and the fly didn’t close with anything but you could go commando in them and nothing would escape because they were so well cut. He sold that business for some seriously good money at exactly the right moment.

That New York scene was a very small number of people, but they were all around Jeremy Henderson. He was like Natas or Dressen, he was that level of cool. Gonz had this reputation of being cool, but part of that was because he had a great desire to be cool. Natas was just naturally cool. Lovely guy.

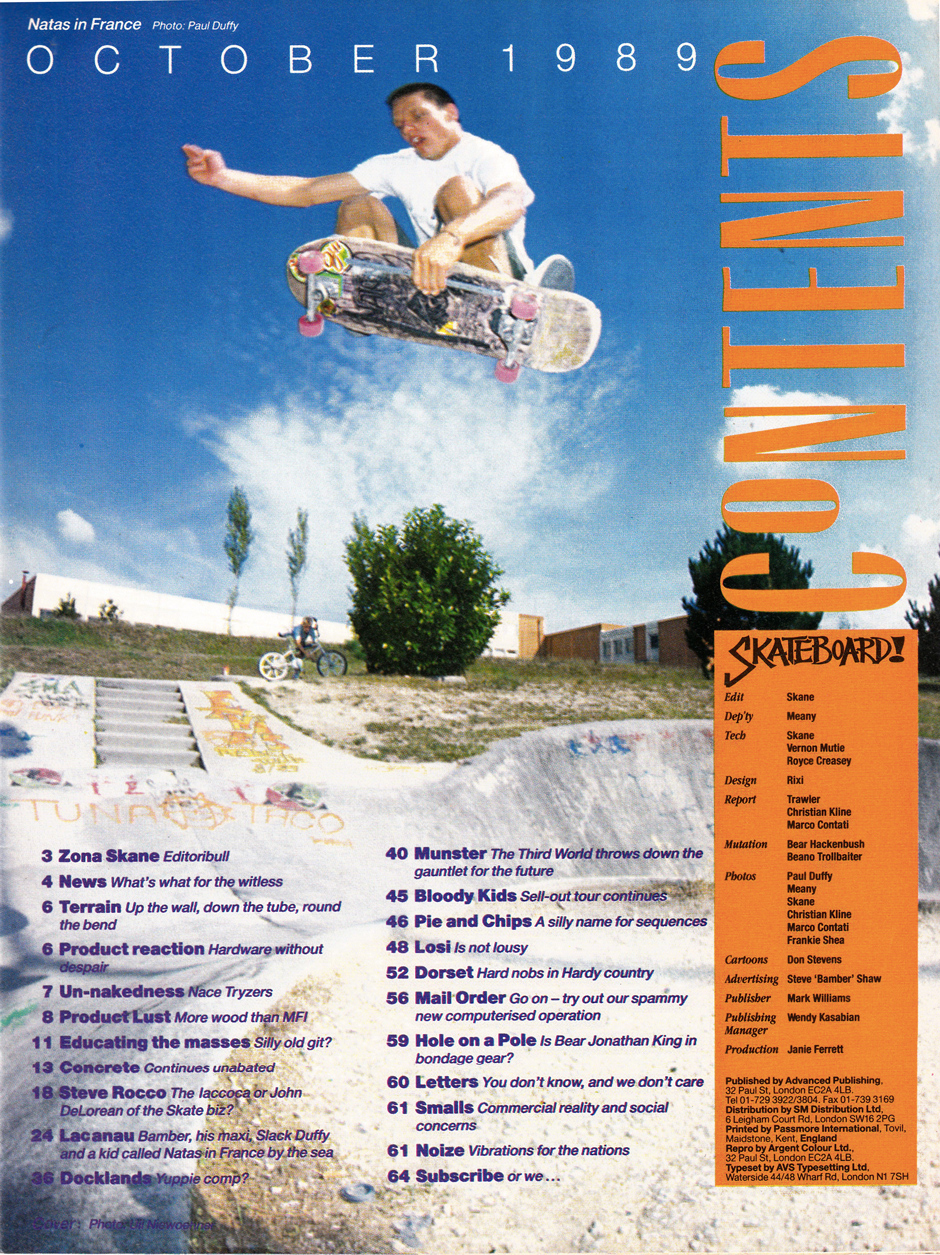

Skateboard! Masthead. Natas Kaupas french floatation. Photo: Paul Duffy

Who else was surprisingly cool? Who was a dick?

I don’t think I came across any UK skaters who gave me any serious trouble, and in America it wasn’t really to do with who was a dick, it was more about who was or wasn’t cool.

I went to the Ghost Bowl with the Alva boys, Jef Hartsel and those guys, and they were 100% cool, they were all very nice people. Jef Hartsel had an intellect; he read books and he had opinions on stuff. He was a fan of reggae music, but he was also into Joy Division and stuff like that, you know? He was an interesting guy.

When I’d go to trade fairs and things like that, I’d be more likely to hang with the guys who were making the stuff, because they were much more interesting. A lot of skaters are seriously boring. Especially American skateboarders, none of them were interesting enough to be a dick.

Tony Alva in the ghost bowl in 1988. Photo: Steve Kane

You mentioned earlier that you were getting 30,000 copies of the magazine printed. Was that peak circulation?

Something like that, yeah. About that. RaD always sold about ten percent more than us, but that was the BMXers. We were probably around 26,000 or 27,000 most of the time, but 30,000 is a nice round figure to tell the advertisers and I think a lot of copies got read by more than one kid. Read by the whole skatepark, or the whole street.

That’s a lot of kids and I didn’t really think about it at the time but if I’d become a teacher or a university lecturer I wouldn’t have had nearly so many eyes and ears paying attention. I might not have a page on Wikipedia but so what? I was able to talk to people like you when they were 13 or 14 and that’s when stuff really sticks. Even the stuff you read when you’re 18 doesn’t stick like it does when you’re 13.

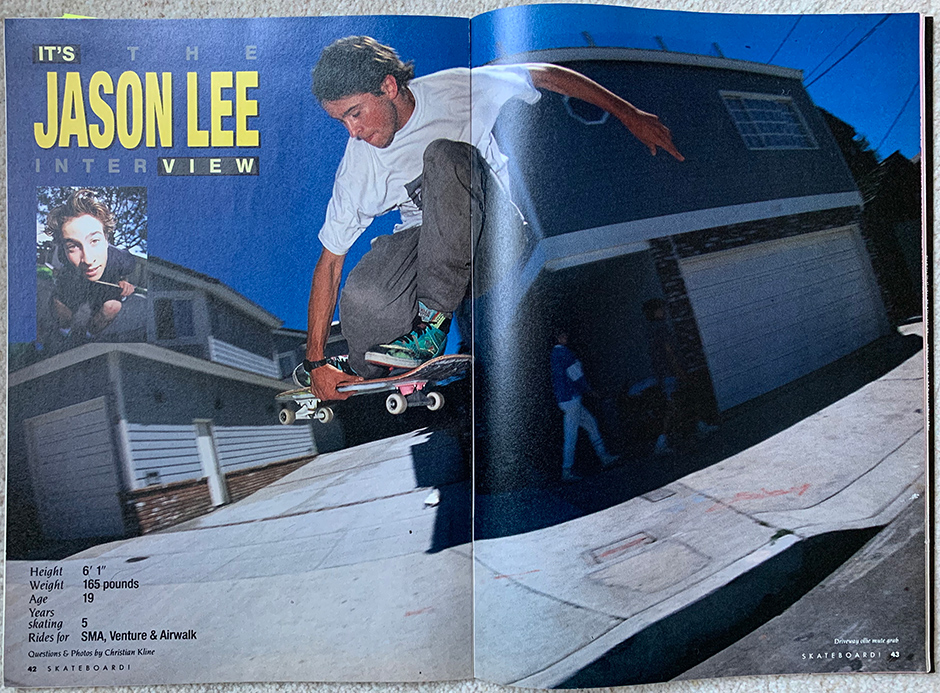

Some reading material which stuck. The Jason Lee Interview from 1989. Photo: Christian Kline

You weren’t heading up Skateboard! for all that long…

Three years.

…but it was during the time when everything completely changed. A photo today isn’t drastically different from a photo from 2017, but the difference between what was happening in 1989 and what was happening in 1992 was enormous.

Yeah. It was an interesting time in general. There was a lot of other stuff happening and skateboarding was right in the middle of it all. Quite often skateboarding got ignored in later history, but if you looked at pictures of regular people from the time, they’d often be wearing skate clothing. And where did that come from? Or it was skaters making the good music.

You didn’t really cover London. Was that because Tim had the London coverage sewn up?

We had some London coverage, but I think I just didn’t want you 13 year-olds who lived in whatever little town to think that London was all there was. Music’s a great example here… Yeah, there’s been some important music to come out of London, but some of the most important music throughout history didn’t come from London. It came from Birmingham or Manchester or Glasgow or Bristol or wherever. Skateboarding was like too, and it was about taking ownership and not being passive. People could be skateboarders in Leicester or somewhere, and feel like they were the centre of the world.

it was about taking ownership and not being passive. People could be skateboarders in Leicester or somewhere, and feel like they were the centre of the world

London’s always had an amazing scene though.

I always found the London skateboarders rather boring. Trying to recreate the Southbank, for fuck’s sake. You can’t recreate the Southbank without the glue bags and all that stuff. That was what the Southbank was all about. You used to be able to skate from the Southbank to Greenwich. It was wasteland, but it was skateable, and now that’s all gentrified.

The Southbank that’s there now isn’t the Southbank. Some of the concrete might be the same, but it’s all covered in graffiti and that was a culture that came later. The people saving the Southbank aren’t the original people, they’re the ones who came just a bit later in the main, so it had already become mythologised for them, and it’s gentrified. I kind of hate it, in a way, because it kind of stops people thinking that what they’re doing is important skateboarding too, if they aren’t doing it in a certain place. They should have just built the new park there, like they wanted to.

But fundamentally Southbank is a great skate spot, it’s also easily accessible and it’s undercover. Why is that bad?

Because it doesn’t need to be this sacred thing. The last time I went past it nobody was skating the banks, they were only skating this block. There were people shooting a music video. The banks are getting used again, and that’s kind of nice, but I’d much rather hear about London skateboarding being vibrant, with new places to skate.

Most places, apart from Livingston and Dean Lane in Bristol, have lost the original place to skate and they’ve had to find new places, and to me skateboarding was always about finding new places. Skateboarding shouldn’t be about finding one spot and skating it every week until it becomes a bust, you know? Skateboarding is about moving all the time. New ways to approach the terrain.

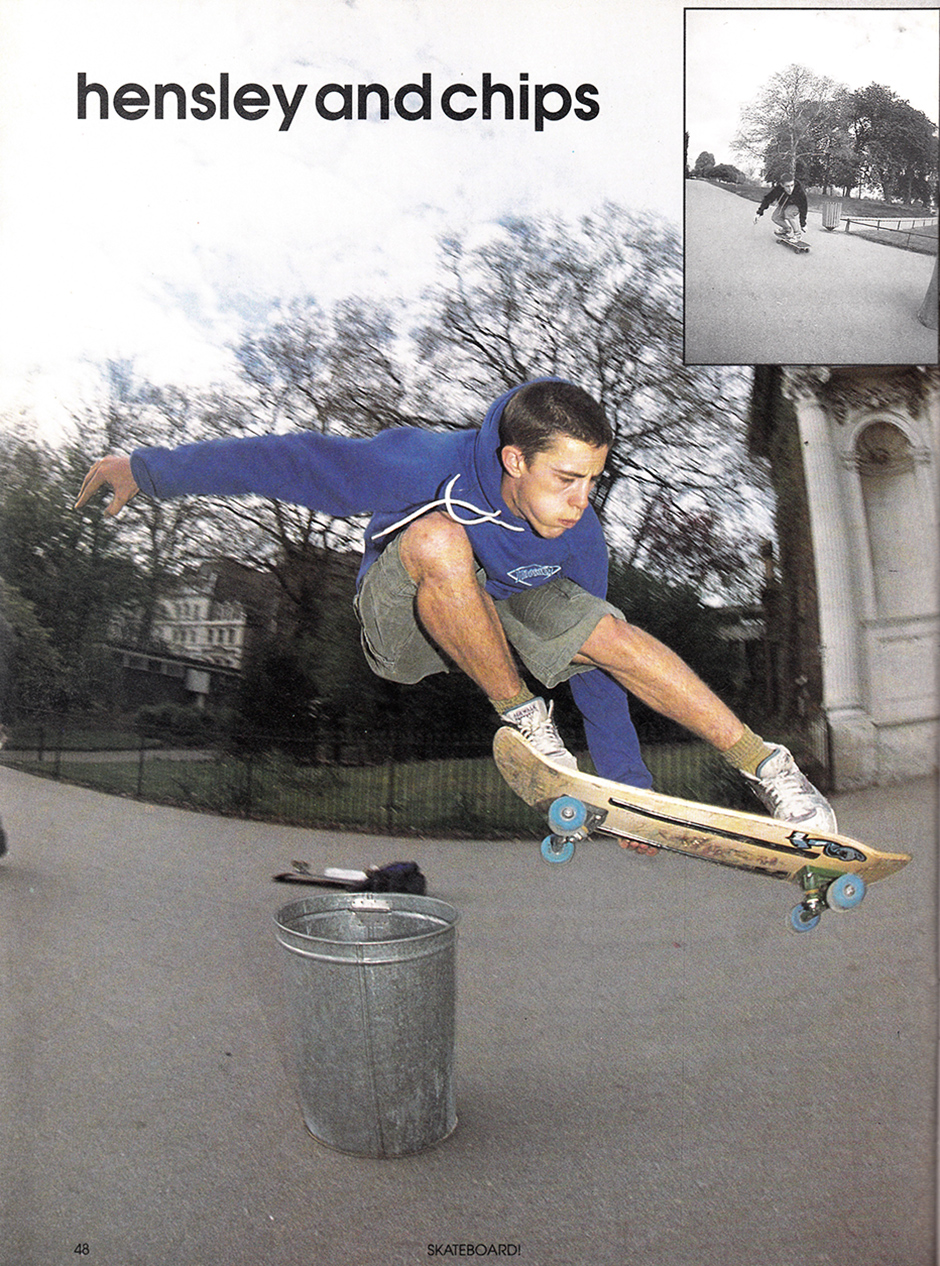

Matt Hensley’s melancholy will forever be stuck in our heads. Photo: Ian Lawton

Skateboard magazines from back then are still pretty important to people. Those photos really stuck in people’s heads and people still care.

I realised that when I first got on Facebook, and some skaters started to pop up and say things like that. After my first marriage, I had this five year window, where I spent three of those years doing a magazine, so hopefully my life hasn’t been a waste.

You and Tim changed how we saw skateboarding here in the UK when skateboarding was going through its most dramatic changes.

The really important thing is that companies started to genuinely be owned by the actual skaters then. It wasn’t like Powell Peralta. It was genuine and it was skaters taking the risks with companies, and they didn’t always succeed but they had their two or three years in the sun and they learned stuff and they could go off and do different things with the experience from running a skate shop or a clothing company or whatever. That’s what was important.

What do you do with your time these days?

I haven’t been skateboarding. My surgeon says I should be able to again, once my knees are healed I’d be happy to get back to being able to walk further. My wife retired recently, so we’ve had to create a ‘new normal’ since lockdown, really, but I have limited energy. I can do something for three or four hours in the morning but then I’m fucked.

Thank you to Steve for taking time out of his busy schedule to talk to us and share these memories. Most of all thanks for all those issues of Skateboard! All mag scans courtesy of @scienceversuslife

More interviews by Neil Macdonald: Sam Ashley, Pete Thompson, Tobin Yelland, Carl Shipman, Corey Duffel, Eli Morgan Gesner, Jeff Pang

More on skateboarding magazines: Michael Burnett Interview, Lightbox: Gino Iannucci by Ben Colen, Lightbox: Jake Johnson by Jonathan Mehring