INTERVIEW BY NEIL MACDONALD (@SCIENCEVERSUSLIFE) / Self Portrait

Not only is Tobin Yelland in the fairly unique position of having shot for each of the main US skateboard magazines—simultaneously at times—but it could reasonably be said that he worked with each one during its most pivotal era. Shooting for Thrasher when San Francisco street skating truly took hold, Transworld during the infancy of the tech skating boom and shooting Europe 1995 for Big Brother, it’s not by chance that Tobin and his camera were in the right place at the right time, again and again. Chances are that your favourite skateboarder, spot or style of the time looked so good because it was Tobin behind the lens, shaping our view of what was going on during these defining times and humanising the people doing it. These were the people truly pushing skateboarding, familiar names or not, and Tobin’s compositions and techniques ensured that we noticed, and remembered.

Skate or otherwise, Tobin’s photography captures the feel of places in time unlike anybody else has, and his ethos of shooting as much as possible has yielded some of the most memorable, iconic images in skateboarding. He’s recently revisited his enormous archive in order to make many of these incredible images of skateboard history and progression available in his new shop, so I called him up to find out about his past, present and future as a photographer, videographer and otherwise.

You’ve been using lockdown time to organise your archive, right?

Yeah. As we quarantined I started going through a load of my photographs that I’ve never scanned before, and that never were published before. I’m getting a chance to scan things and have more time to look at everything I have, which is so nice. It’s so nice to be able to share that work because I’ve had so many years of making skateboard photos—and I continue to make skateboard photos, although not as much as I did twenty years ago—and I love getting to go into them all. It’s really fun to share.

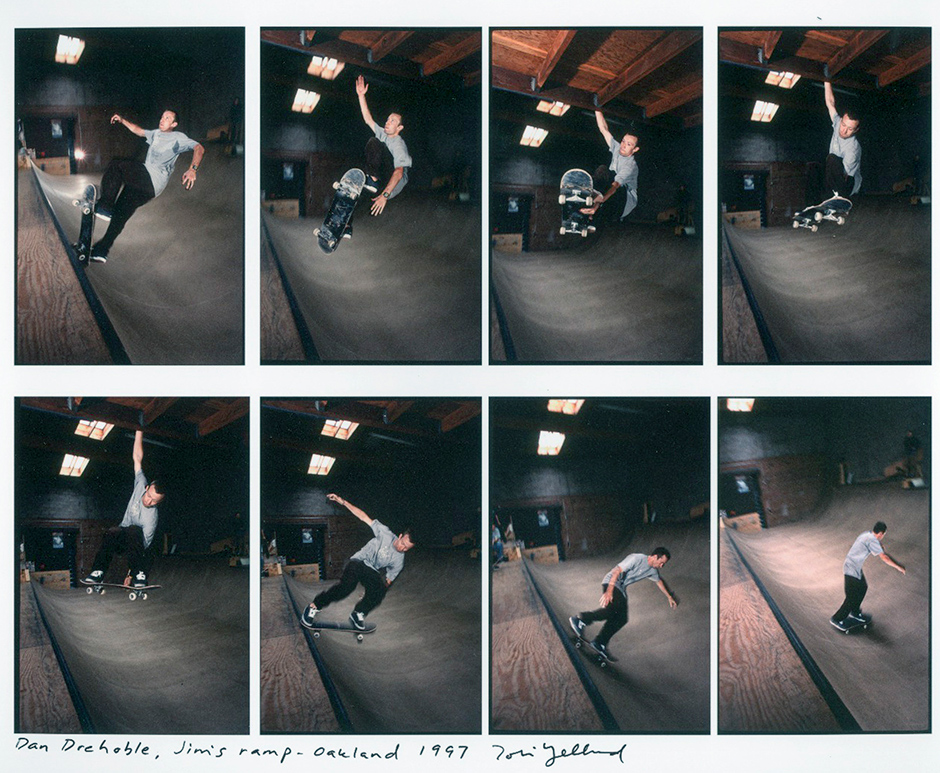

Like yesterday, I shared a sequence I shot of Dan Drehobl skating Jim’s ramp in Oakland where he does this ollie lien grab, and there’s a rafter about eight feet above the ramp, and he grabs it with one arm, looks at the coping and comes back in with a tail-tap on the coping. He’d never seen it before and it had never been published so I scanned it and made a quick edit so you could see the sequence on Instagram. It was really fun to share that with him. There are lots of moments like that.

Dan Drehobl dangles at Jim’s Ramp in Oakland. Photo: Tobin Yelland

Have you got a favourite shot that never ran in a magazine?

Hmm. Well, right off the top of my head, I have an image of John Cardiel at Embarcadero in San Francisco in 1993, and it’s just an alternate angle but it’s one I like. One of the photos ran, where he’s ollieing a gap the opposite way from the Gonz…

From Big Brother issue five.

That was so long ago! The other angle is like is kind of a butt-shot but it shows him ollieing and I really like that photo.

Alternate angle of John Cardiel going his own way at Embarcadero. Photo: Tobin Yelland

The one that ran is interesting. It’s shot really early. It’s the take-off, and I feel like another photographer would have shot it at peak height, or with him in the landing zone.

Think of it this way. We see that same thing over and over again, and a lot of pictures are of ollie tricks, and that’s a picture of John ollieing a gap. He’s high off the ground—I think he might be eight feet off the ground—so there is an element of danger, and I really like that image of him just taking off because it really shows that it’s a huge gap. I feel like it’s sixteen feet long, and that’s a big chance to take when you’re already eight feet off the ground. He’s much higher than me; I’m six feet tall, and it’s a long gap, so I think taking it early and showing him taking off really lends something to all the empty space that he has yet to go through.

That works because it’s John Cardiel, and you know that he will actually have moved through that space.

Yes. On that same note, in my experience a lot of what dictates what photographs get run is the photo editor at the magazine. At that magazine it was Jeff Tremaine who laid out that article—or Natas maybe, Natas was doing some design for them—and it’s really up to them what they show or don’t show. It’s really fun as a photographer shooting skating because you don’t know how many tries you’re going to get to try out different angles or anything, and I think with that one I had maybe five tries. It’s really fun to try different things because if you’re doing the same thing over and over again it gets repetitious.

More Cardiel from his Big Brother interview.. switch frontside heelflip. Photo: Tobin Yelland

How much of your archive do you still have? You always hear about boxes of slides or negatives getting lost or ruined.

I think I have the vast majority of my work. There certainly are images that are missing that I won’t see again, but I’m happy with all my images that I’ve been able to keep. And I’m really happy that I own them all, because it’s different with different photography genres. Like people who do film stills, for films, they don’t own any of the images. They can show them in their portfolio, but they certainly can’t sell prints of them. At the end of their career, what do they have? They have images they can share, but they don’t have anything that they own, so I’m happy that I own these images.

It’s really been helping me through the pandemic, when there’s no photo shoots happening. I’ve had a lot of time on my hands so it’s given me the opportunity to go in and make scans and do all the Photoshop work, the retouching and all that work that’s involved in sharing a photograph. I think the most work has been looking through pages and pages of shitty photographs that no-one’s ever gonna see! There are all these sequences, so you really need to look at everything. It’s like panning for gold, looking through hundreds of rolls of films to find things to share. And I’ve got a lot more to find. A lot more to look through.

I’d heard you were planning a book of skateboard photos… Are you planning book of skateboard photos?

I’m still making books, but I’m not sure what form they should take. I do have a hard time editing books, which is why I haven’t been able to produce a book so far. I’ve had a few opportunities to make a book but I hadn’t really felt comfortable with the publishers and what they wanted to do. Oftentimes when you have a body of work, they want to make what they think your book should look like, and not have you involved so much. I feel like because this is all very personal work, I’m fine with taking my time and making books that feel right, that feel like they’re made by me. To be honest it’s not something I love to do… It’s so much damn work and it’s something I easily put off, so that’s why I haven’t made one. But I will make books, and they will come out!

I have a few different ideas—maybe people reading this could tell me what they think I should do—but one idea is to make a book of just skate shots. Just colour action shots, like magazine photographs. Maybe have a few portraits, then all action shots. Maybe that’d be fun because I really like looking at your Instagram feed (@ScienceVersusLife), and @koolmoeleo and @lookbacklibrary, and it’s cool to flick through that like it’s a skateboard magazine.

Initially I thought my first book would be Northern California skateboarders, but documentary style. My friends and skateboarding. I’m not sure what it’d look like but I’ve been working on it and have a few different versions of that, but I’ll continue to work on it. I’m going to make a lot of books!

The portraits from that era are important too, to show what the people were like. Bangers are great but it’s good to see how somebody chills too.

It’s fun. I feel like the more time that stands between us and the time when a photograph or video was taken, the more cherished that moment is because twenty or thirty years is a long time, and you realise after time has passed how precious those moments were.

Back when I was photographing, oftentimes there wasn’t a video camera around, or there’d be a video camera but no stills. And talking of magazine editors making the decisions about what went in, there are a lot of goofy photos that didn’t fit the magazine’s idea of what should be published and they’re still there.

I feel like the more time that stands between us and the time when a photograph or video was taken, the more cherished that moment is

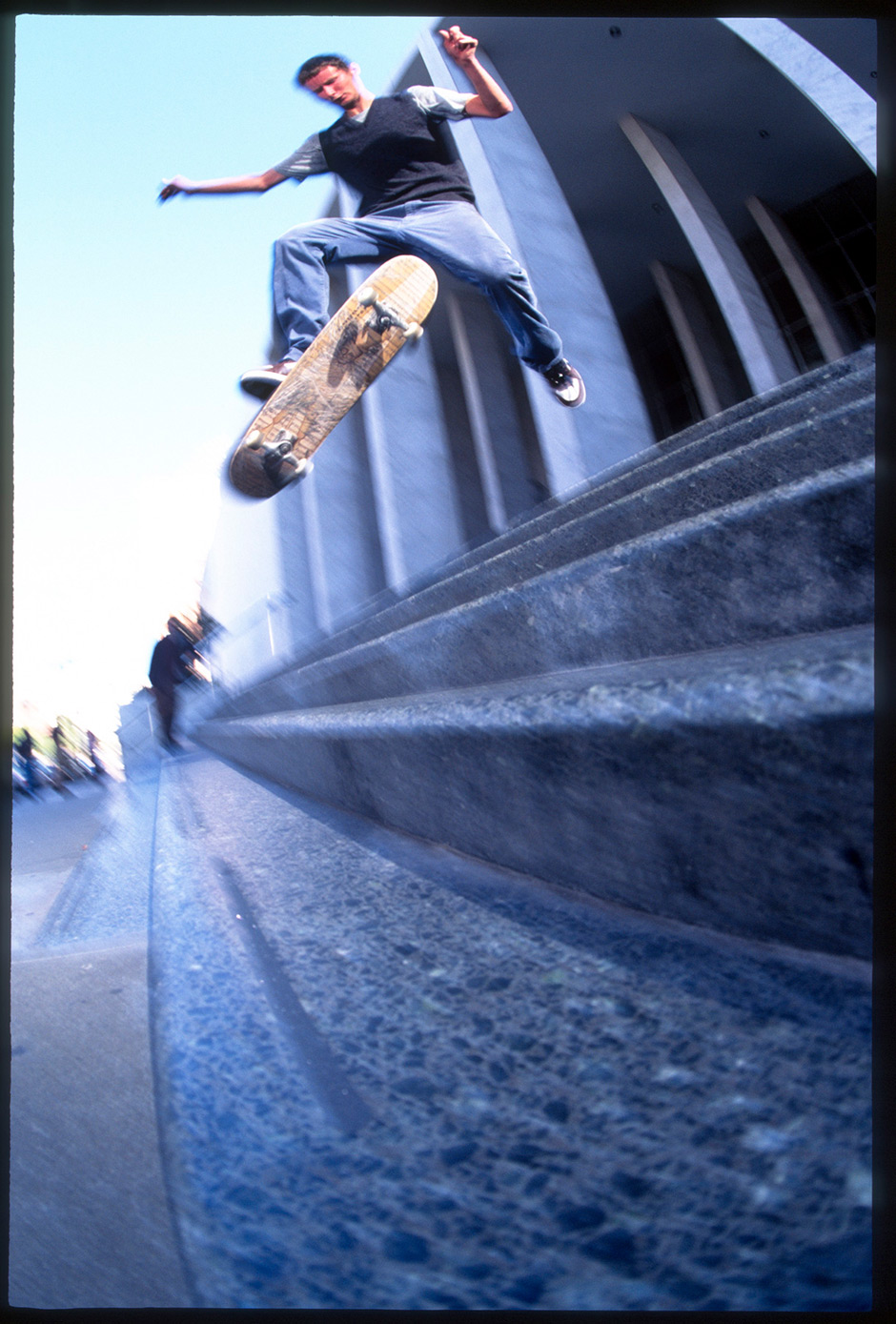

No discussion on including this Justin Girard back smith from 1991. Photo: Tobin Yelland. Inset below – Fogtown No Ploys No Toys ad

Say I’m looking at a bunch of photographs of Justin Girard, and I’m editing them to what I think a photo editor will want to buy from me, that’s a little different to what I think an interesting photo looks like but an interesting photo to me might not fit the magazine’s idea of what they want to publish. It’s fun to be able to look at all these different photos that weren’t used and share them with the people that I made with with, because skateboard photography is a project. It’s a project with a skateboarder and a photographer; you’re making something together.

Whether you’re making photographs or a video, it’s a collaboration between the cameraperson and the skateboarder. It’s really fun to share those moments years later, because time goes by so fast and sometimes you have fuzzy memories of those days, but it’s a whole other thing to see a photo or a video clip that you’ve never seen before, or that you haven’t seen in a very long time.

You starting shooting for Transworld pretty early, so who did you come up with? Did your friends happen to be the guys that the magazines wanted photos of?

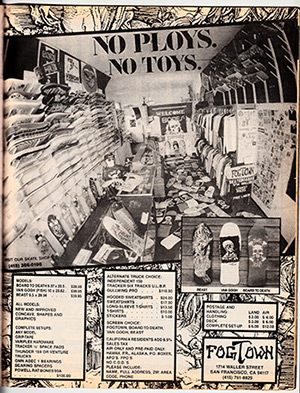

I started skating when I was 13, and when I was 14 I started taking my first photography classes. I grew up in San Francisco and one of the biggest skateboarders in San Francisco was Tommy Guerrero, and I was a kid when he was an amateur skateboarder. I would go to the skate shop that he worked at—it was called Fogtown—and he was a really nice, funny kid.

I started skating when I was 13, and when I was 14 I started taking my first photography classes. I grew up in San Francisco and one of the biggest skateboarders in San Francisco was Tommy Guerrero, and I was a kid when he was an amateur skateboarder. I would go to the skate shop that he worked at—it was called Fogtown—and he was a really nice, funny kid.

I knew it was a big deal when he got on Powell Peralta, and became a professional skateboarder. I got some shots of him, but he was a big pro skateboarder who I looked up to. So was Bryce Kanights. And then the whole Concrete Jungle team, which was the skate shop after Fogtown. They had a super good skate team, and when I worked there, when I was 14 or 15, they had Mike Carroll, Jef Whitehead, Mic-E Reyes, Danny Sargent, Shawn Martin and Mike Archimedes. Amongst others.

So you’re already around the people that any photographer in SF would want to shoot.

Yeah. Also, around that time, when I was 15—and I’m 49 now—skateboarding was small, it was not a huge deal. It was not something that was widely accepted; you’d get made fun of for being a skateboarder. We’d all meet at the Boys’ Club, near Haight Street, where the skate shops in the City were. Later there was FTC, which started up downtown and ended up on Haight Street. So we’d all hang out at the Boys’ Club, every skateboarder in San Francisco, and then there was a vert ramp in Hunters Point that we’d skate, and there was The Dish, the skatepark in San Francisco, but other than that there was no skateparks and very few pro skaters. Just a handful of pro skaters.

So I got to know these pro skaters, and I got to know and photograph all the kids I grew up with. I got to do a lot of practicing and I got to take a lot of bad photographs.Photographing my friends allowed me to feel comfortable around people, so I could ask them to do the trick over and over again. When you’re with each other all the time you have a really relaxed feeling about getting your picture taken.

Tommy Guerrero continuing to inspire years later. Dogpiss Air in 1997. Photo: Tobin Yelland

There’s normally one photographer for each crew of skateboarders, so did you have much opportunity to meet other photographers?

The other photographer I met right away was Luke Ogden, we met at the Boys’ Club ramp. We took a summer class in photography, in shooting skills and processing and printing your own film. Soon after that I met Gabe Morford. I had a Minolta camera, and he had one too, so when I switched to Nikon—when I sold my bass guitar to get a Nikon F3—I sold my Minolta fish-eye lens to Gabe Morford and that’s the first time I met him. He’s from Marin County, which is really close to San Francisco so I got to meet him really early.

The older photographers in the community were MoFo [Mörizen Föche], who was at Thrasher magazine and I met him a few times but I didn’t really see him out very often… I saw Bryce a lot because Bryce was a pro skater and he would skate everywhere. Bryce helped me out a lot, by inviting me to go skate places, and I’d give him photos I’d shot which he would take to Thrasher to see if they wanted to use them.

Alternate angle of a julien Stranger front board which ran in Thrasher Feb 1988. Photo: Tobin Yelland. Inset below – Jovontae Turner grabs melon in the avenues in 1990

So Bryce was shooting photos for Thrasher while he was pro for Schmitt Stix?

Yes. He was doing both, he was a pro skater and a photographer at the same time. Also Kevin Thatcher was an influence for me, he was the editor of Thrasher and also a photographer. Who else… Craig Stecyk I would see around every once in a while. I think he spent a lot of time around High Speed Productions but I didn’t really know him.

And then Lance Dawes. I met Lance Dawes at a skate contest before he worked for Slap, when he worked for High Speed Productions, and he’s just the type of guy that can do anything. When he started photographing he very quickly got really good and was able to be the editor of a magazine, able to put everything together. He made a great magazine for a long time.

Then there’s Skin Phillips and Thomas Campbell. I watched Thomas Campbell learn how to do skate photos, because when I first met him he was a writer. He did the interview with Julien Stranger for Transworld, and that’s the first time I met him, down at NHS where Santa Monica Airlines was being done at the time.

You were definitely amongst the people shaping the world’s perception of modern street skating so your own standards must have been pretty high, whether you knew or not. When did you start getting your photographs published?

Yeah, I think so. It was a long time before I got anything published, and I have to say that only once was I given a monthly retainer, and it wasn’t really very much money. I was never on the payroll of a skateboard magazine. When I started out you could either work at a magazine like a regular job, Monday to Friday, and get a pay cheque, or you’re a contributing photographer like I was. So we’d go out, I’d photograph you doing a tailslide on that cool ledge, then I would make that photograph and figure out who might use it, whether that’s a magazine or a company you ride for.

Yeah, I think so. It was a long time before I got anything published, and I have to say that only once was I given a monthly retainer, and it wasn’t really very much money. I was never on the payroll of a skateboard magazine. When I started out you could either work at a magazine like a regular job, Monday to Friday, and get a pay cheque, or you’re a contributing photographer like I was. So we’d go out, I’d photograph you doing a tailslide on that cool ledge, then I would make that photograph and figure out who might use it, whether that’s a magazine or a company you ride for.

That would determine the price I would get for the image. They would put it in the magazine whenever they chose. That wouldn’t be up to me. Companies have their own rates for photographs, and magazines have their own rates which they pay you whenever, or in a couple of months when the magazine comes out, and they determine their own page rates. I think when I started it was $80 for a black and white page, and maybe $100 for a colour page. So I worked for myself and I would just photograph every day, but it took me years to become a photographer. I think it was 1990 when it became my full-time job, but it was barely a full-time job for a while. I was just constantly sending photos to magazines.

You were in all the magazines, which was quite unusual for a photographer then. Was it hard to not have an allegiance, to not be all, ‘Hey, I’ll be your guy!’?

When I first started out, you had to just work for one magazine. There was the rivalry between the Northern Californian magazines, Thrasher—and to a lesser extent Slap—and the Southern Californian magazines, which were Transworld, and then later on Big Brother too. It was like that for a long time, and you really had no power as a photographer. You really had no kind of leverage until you’re getting all the best photographers or you’re such good friends with all the key players that the magazines have to work with you. Eventually that happened with me because I just photographed every day; there was a point when I had so many photographs that I had a little more room to do what I wanted. For a long time it’s just up to the magazines or the skateboard companies how much you get paid, until maybe they realise that you have what they want and they need you more than you need them.

Right when I started out there was very little freedom and making photography a job was a scary thought because it was very inconsistent. That’s the reason there weren’t as many photographers around, it was very difficult to pay rent and bills with that sort of job. I lived off of beans, pancakes and sardines for a while. All my friends who were pro skateboarders got paid maybe $300, $500, a month which is about enough to rent a room, but we were all reliant on getting free boards and selling the free boards. To put gas in the car to go on an adventure, we would load the car with product because when we get to that first skatepark or town, we’d sell all the product and use that money for gas and food.

Right when I started out there was very little freedom and making photography a job was a scary thought because it was very inconsistent. That’s the reason there weren’t as many photographers around

Were you getting free film from the magazines, at least?

Oh yeah. Free film from the magazines was really the best part about that job. I’m looking through all my photographs now, and there are some amazing ones I shot on Kodachrome 200, and I remember when I got lots and lots of Kodachrome 200 from Grant Brittain, and it was seriously the best film. The Kodak slide films were really good too, but for a while I was shooting a lot of Fuji Provia, pushed one stop.

Could you tell the magazines what film you wanted, or did they have a preferred film for their style?

You know, I can’t really remember. But I remember Grant being really good to me with film. I was really terrified about not making enough money to pay my bills, so I would photograph every day. For a while Luke Ogden and I had the biggest body of work at Transworld because we just shot so much, so they would always send us film, and they loved getting shots from Northern California.

It felt to me like the way you were shooting, or the ‘tone’ of how you shot, for Transworld, went on to inspire the aesthetic of Stereo, and then Anti Hero. Was there any issue with you going from Transworld to Deluxe?

Well it’s really a very small world. Deluxe was the closest company to me, in San Francisco—it was at a bunch of different locations over the years—and a lot of my friends skated for Deluxe or worked for Deluxe. It’s funny because Luke and I were the youngest skate photographers in San Francisco who were published, and Gabe Morford was from Marin until he moved to SF, and he was a little younger than me and Luke. At one time Luke and I were the photographers supplying Deluxe with all the photographs for their ads, and then the guy that ran Deluxe, Jeff Klindt, hired Gabe Morford as their full-time photographer. Jeff was also a sponsored skateboarder, and I think he skated for H-Street.

He did, and he drew the Hensley stained-glass graphic.

Yes he did. And he drew many of the first Real skateboard graphics; he was really creative and talented. When I was 19 years old, Gabe’s a little younger, and he takes over all the photography for Deluxe. As far as Transworld and Deluxe… There were so many different outlets for photography, and in the early ‘90s there wasn’t that many photographers. I lost that job when Gabe went full-time, and he’s been there for over twenty years now, so it was a great deal for him, but there’s always been other outlets to photograph for. I photographed for Julien and Anti Hero for the first year solid, I was their photographer and video person, and a lot of my personal photographs would make it into advertisements, if Julien liked it. He was the art director, for lack of a better word, although I don’t think he’d like to be called an art director… He’s the creative voice behind Anti Hero.

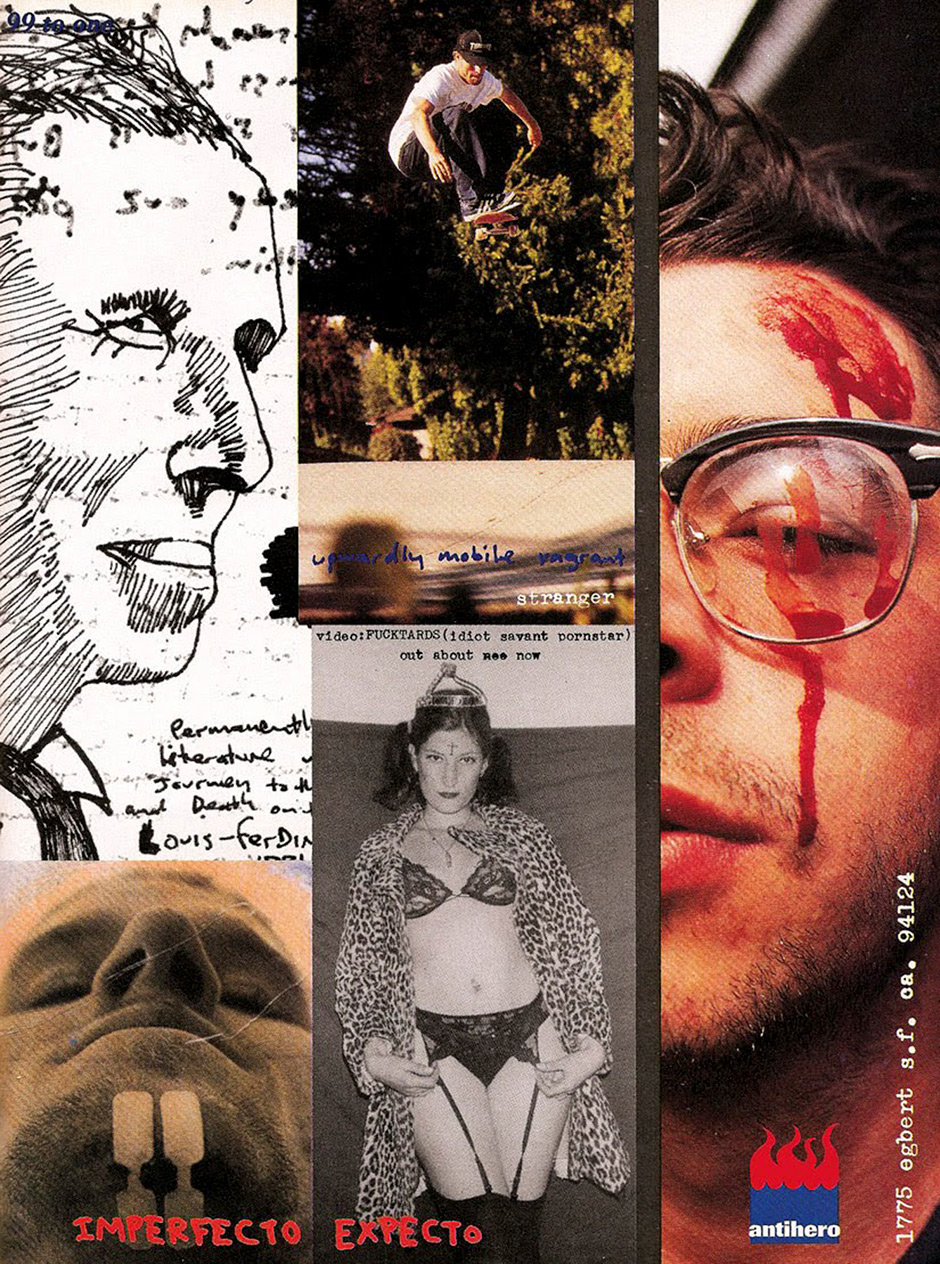

Julien Stranger Anti Hero ad featuring Shana & Dave Carnie

I was just looking at an old Anti Hero ad today, of Julien doing an ollie at Benicia, and there’s a picture of my friend Shana dressed up in some sexy outfit or something, and then right next to that there’s a picture of Dave Carnie right after he had an accident. He was framing a photograph and he hit himself in the face with a crowbar and he has blood running down his face, but it wasn’t that serious. Part of the fun of being a photographer is just taking a lot of silly, silly photographs, and there was a time when you couldn’t really get a silly photo in a magazine. It always had to be a skate shot, or a portrait for a Who’s Hot or whatever. And then Big Brother came around, and Big Brother wanted mostly ridiculous photographs! They wanted good skate shots too, but there was a nice kinda freedom that I think that brought.

Was A Visual Sound the first video you made?

Hmm… I’d shot parts of Skypager, the Underworld Element video.

You must have shot Julien and Rick Ibaseta for that?

I shot Rick Ibaseta’s part, although not all of it because I think Chris Ortiz shot some of that stuff too. I shot half of, if not most of, Julien’s part and Chris Ortiz shot parts of that too. But what else..? Hmm… I think I shot some stuff for 411. I think I started shooting video out of necessity because I was the only camera-carrying person at a session, and people like Julien and Rick would be sent a camera from the skateboard company, to film their parts. I did some parts of Transworld videos, so those videos could have been before A Visual Sound, but A Visual Sound was the first real video I shot a lot of the footage for.

I think I started shooting video out of necessity because I was the only camera-carrying person at a session

And the first video that you were able to conceptualise? It was pretty different to what had come out before.

I didn’t conceptualise A Visual Sound, or Fucktards. Some parts of Fucktards were my ideas, like there’s a PixelVision part, the artsy black and white part in the middle, but it was all Julien’s concept. I was in the editing room and I might have had some ideas, but that was Julien’s concept. I think a lot of my collaboration with Anti Hero was just because I liked to shoot everything. The credits for Fucktards was my friend Jessica, and I was just shooting with a Super 8 camera, moving up her arm to her face, and I just shot that on my own when I was hanging out with her and that happened to be a piece of footage that Julien wanted to use.

A lot of my collaboration with Anti Hero was just photos of other stuff that I’d taken, that Julien chose to go with skating. A Visual Sound was Jason Lee and Chris Pastras all the way, as far as the jazz and the editing and all that. I was the shooter, and I’d just be with them constantly, shooting video.

Whose idea was the 16mm for these videos?

Well that was influenced by me. I just loved to shoot film; I love the way it looks. I bought my first projector and I borrowed a really cool Bolex Super 8 camera from my friend Xiou Ping who was going to art school. This little Super 8 camera that looked like a Star Trek phaser gun—it was a Bolex 155 Macrozoom—and it shot at 18 frames per second natively, but then it had a button right on the handle that said ’32’, so you’d press that button and it’d turn into slow motion.

I shot a cool clip of Ethan Fowler in the Stereo video where he’s approaching the bench at Union Square, to do a backside 180 over, and you could speed ramp it so when he’s in the air I press this little button to slow it down, then he lands and I press the button to speed it up again. That was really fun.

That sounds fun but it sounds risky too. Did you go through a lot of film making stuff like that happen?

I would say that we shot very little film. I think we just used what we had. As I remember it, I was shooting Super 8, I had my own cameras—I bought my whole set up from my friend James Harbison—and I would bring it with me everywhere. It had a microphone attached to it, and Super 8 sound film has a strip on the side of the film that’s the sound. The sound gets recorded to that piece of film.

I’d give Chris Pastras the little microphone when we were skating, and he’d start being the announcer, in this funny announcer voice. I think Chris and Jason saw me shooting Super 8 and then wanted to incorporate that. They’d visualised how the intros would be in A Visual Sound, the still photographs with the Super 8, and they wrote those pieces. Like Mike Daher lighting a match then throwing his board down and skating down the street.

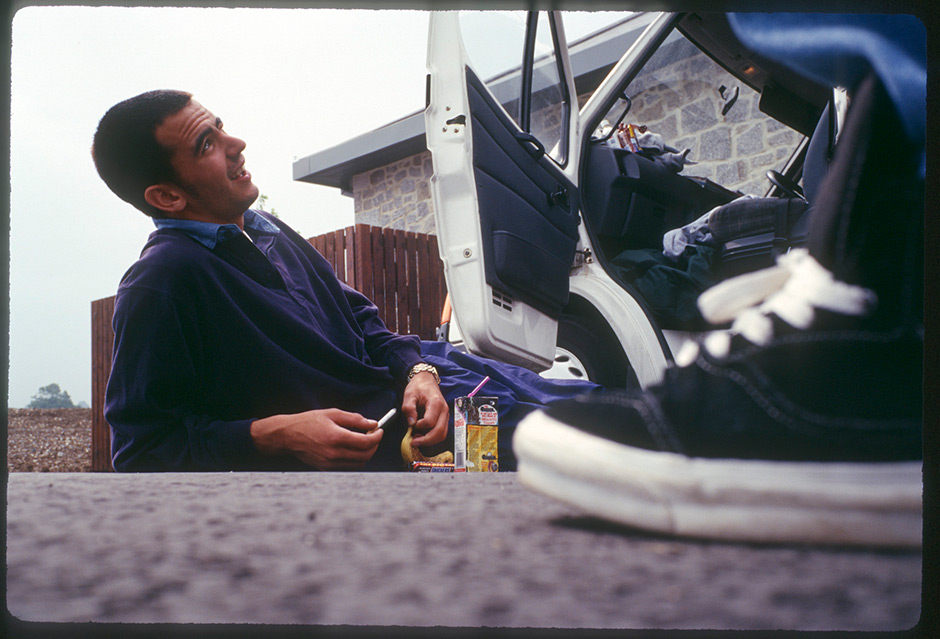

Matt Rodriguez on the beach.

Yeah. So they wrote those and I would shoot them with a macro lens, which was really fun. I think Gabe Morford shot Jason Lee’s intro, on colour Super 8, where he’s riding a bike through a park. My favourite was Ethan Fowler. We filmed his part in two weeks, then his intro, which had no skating in it, was the last piece that we needed to shoot. He came up with the idea of just walking and transitioning in and out of the frame.

Did videos like A Visual Sound and Fucktards have strict deadlines? How did you know when you were done?

A Visual Sound had a deadline, so we just shot as much as we could. There were some things that never made it in, but all the good things made it in. It’s like when you asked earlier about when you’re shooting with film and have a limited amount of images. If I have ten rolls of film in my camera bag, that’s 360 photographs, so if I’m out for the day and there’s no place to buy film then that’s all I have and that does create a sense of urgency.

I’m sure we’ve all found ourselves facing a decision, and we can’t decide, so we just don’t do anything. But if you and me are out and you want to shoot a sequence at a gap, then we’ve got four or five attempts for each roll of film. And if you don’t make it, I’m throwing that film away. Haha! But once we’re on the tenth roll, you just have to decide if you’re going to make that trick. For that last roll of film. We could come back another day, but I really like how film creates that urgency. In another respect, it does create a lot of stress too!

I was shooting Jim Greco a couple of years ago for his movie, for Jobs? Never!, and he’s very aware of how much each minute costs. That was 16mm, and there’s not that much price difference for processing and for transferring the video, but the film costs more money that Super 8. So we have eleven minutes on a 400 foot roll. Eleven minutes of footage, right? So he’s constantly asking how many feet we have left. And if he wants it in slow motion, then it burns faster, so if we shoot at 60 frames per second, that’s going to burn three times as fast as regular speed. So when we get down to about 50 feet, he’s got to make his trick, otherwise he’s got to get it on video and then make it look like film or transfer it or do whatever he wants, but there is that urgency that film creates.

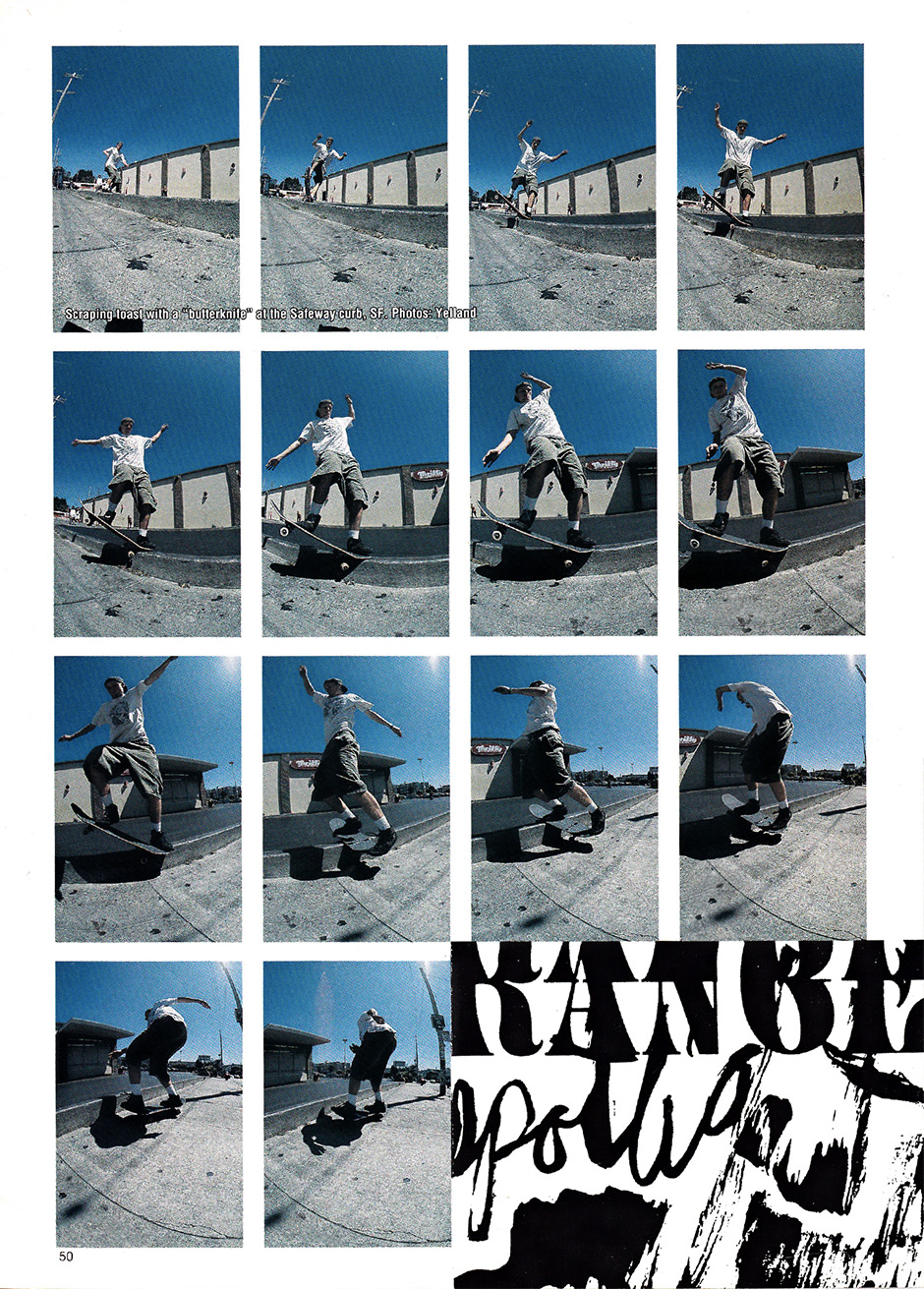

No apologies for the third Julien stranger appearance. More fire at Safeway 1992. Photos: Tobin Yelland. Inset below – another sequence of signature James Kelch shapes at Embarcadero

How did the cost involved affect shooting sequences?

I didn’t shoot a lot of sequences at the beginning, but then sequences started to become really sought after… A sequence is really a stepped-down version of a video clip. When cameras were slower, with their motor drives, you might get an eight-frame sequence. That was normal. Or maybe twelve. At one point I was shooting a ton of sequences, and I’d go home, process them, print them out and give them to the magazine or the skate company. I’ve got a lot of sequences no-one’s ever seen.

At the time, in ’92 or ’93, there was not always a video camera around and if you’re doing a trick that has a flip to it, or it’s something like a crooked grind kickflip out, then you need a sequence of it because a still won’t tell the story.

When it got to the point where there had to be a video camera there, or the trick wasn’t going to get done, then the role of the photographer changed to mostly shooting still images. Then in the times of the big night shoot, the photographer would be there to get the still but everything else would be videos. I’m sure that’s more important now than still photography.

I’m pretty sure I read once that ‘EMB is the crew, Embarcadero is the spot’, although obviously everybody calls the spot EMB. Which once meant Embarca’s Most Blunted. I think it might have been Kelch that said it and he’d know, but have you heard that?

Yeah, that makes sense. And Kelch was a leader-type person, as well as an amazing skateboarder. EMB was an abbreviation the locals made up, because not everyone was a local. Not everyone that had a skateboard at Embarcadero was a local. There was definitely layers. Kids like Kelch, Mike Cao, Chico Brenes, Jovontae Turner, Henry Sanchez, Scott Johnston, Shelby Woods and a bunch of kids with nicknames like Fat John and Smoove Smurf.

Yeah, that makes sense. And Kelch was a leader-type person, as well as an amazing skateboarder. EMB was an abbreviation the locals made up, because not everyone was a local. Not everyone that had a skateboard at Embarcadero was a local. There was definitely layers. Kids like Kelch, Mike Cao, Chico Brenes, Jovontae Turner, Henry Sanchez, Scott Johnston, Shelby Woods and a bunch of kids with nicknames like Fat John and Smoove Smurf.

A lot of people would just be there hanging out with their friends but a lot of people there were pro skateboarders, or sponsored amateurs, and there was a sick crew. A lot of times they did regulate on who could skate there and who couldn’t skate there. If you were an out-of-town person and didn’t have a nice attitude, you would get vibed out. There was definitely a crew so it makes total sense that EMB is the crew and Embarcadero is the place.

Did you see a lot of people get vibed out? A lot of people wanted photos at that place.

I think the closest thing in the UK is Southbank, and it’s got its locals, and then the other people who travel there to skate. You just have to have people skills. You have your skateboard skills and if you’re a great skateboarder, that’s great, but as far as Embarcadero was concerned, if you have good people skills and could start a conversation with a stranger, it helps. You’ve got to make friends in the first ten minutes! Haha! Ten minutes to prove you’re not a kook!

Skateboard tricks are there for everyone, everyone does the same tricks, so I imagine that if someone comes from out of town who’s just super amazing but comes in without trying to meet anyone, just comes to get a video clip, they might get hated on. If they didn’t try to get to know the locals first.

I remember when John Cardiel came through from Sacramento, when he had more of a kind of heavy metal vibe. The Embarcadero locals had slang for kids who were not inner-city kids, who were kids coming from the country, who were more rockers than into hip-hop and had a different look with their chain wallets, and John Cardiel was one of the guys who looked like that. They called them slash-dogs. Like you’re slashing a frontside grind. Now that I think about it it’s a reference to a pool skater… I think that kind of tells the story of how skateboarding was becoming more hip-hop and more street, and it was clashing with the pool skating, slash grinding side of things.

Barker Barrett skating Venice High. Photo: Tobin Yelland

Punk Rock vs. Hip-Hop. Slap even made shirts of it. So how was your time in New York? Were those guys happy there was somebody from the West Coast coming out, or did you get vibed?

I first went out there when I was 18. I’d met Barker Barrett—who skated for Shut—when he was out in Venice. He was skating Venice High and I got his number, then when I called him to tell him I’d got a plane ticket, he was all, “OK, cool!”, but when I got out there he’d completely forgotten that I was coming so I had to wait three more hours for him to pick me up because he lived pretty far away from the airport. I don’t think he even told any of his friends that I was coming, but I wasn’t a published photographer—I’d maybe had one photo published but no-one knew my name—and I wasn’t a professional photographer. I was just a skater with a camera.

So I got to stay with Barker and shoot him around Pennsylvania, where he lives, and because he skated for Shut we got to go hang out at Bruno Musso’s house. We got to skate with Rodney Smith, and got to skate all over New York over Easter Sunday. We skated a pool actually, somewhere above Harlem.

The friends I met in New York were excited to shoot photos, and I got some really good photos. A few of them got published in Transworld, so that was really nice.

Was there a point where you realised that you were around everybody making a difference in skateboarding? The people you’re skating with and shooting are the people everybody wants to see. On both coasts now.

It just felt like skateboarding was small. It didn’t feel big but it felt very exciting. It’s a big deal to be able to skate New York City with the Shut team, and that was super fun. I know how lucky I was to be able to do that, and what allowed me to do that was meeting people. There weren’t a lot of photographers then, in 1989, when I went to New York, but I met Bill Thomas out there.

That must have helped too.

He was an awesome dude and an awesome photographer, but I don’t know if I’m missing anyone… When I moved to New York in 2001, Giovanni Reda was the main photographer there, and Mike O’Meally was there then too.

You’d already know them from Big Brother, right?

Yeah, but there wasn’t that many photographers when I was there. I feel fortunate to have come into contact with so many awesome skateboarders because when you meet one person, you meet their friends and then their friends and more and more people. It’s an adventure. Each skateboarder that I’ve met has introduced me to so many new opportunities to photograph. I think the best part about being a skate photographer is the friendships.

That’s one of the best parts of skateboarding overall.

Yeah. Skateboarding is about friendship and going skating with your friends, and for me, photography is the same thing. When I stopped seeing my friends around so much and it became more about photographing a lot of people I didn’t know that well it became more robotic and not so fun.

More like a job?

A little bit. But photography’s not really a job if you love it. It’s hard work but it’s really fun.

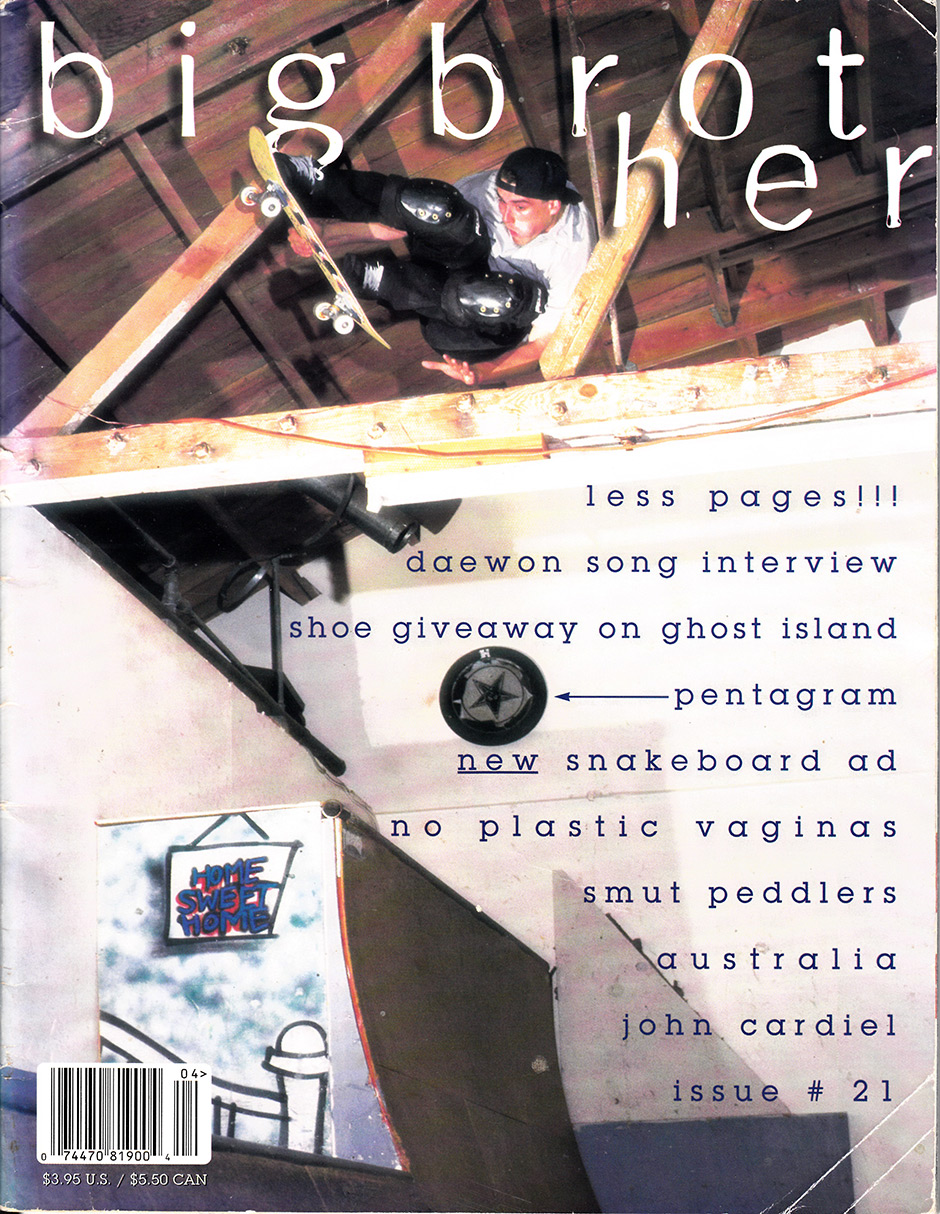

You had photos in all the mags, then when you worked solidly for Big Brother for a while. Did they poach you?

So I photographed a little bit for Thrasher, early on, when I was around 16 years old, then I when I was 19 I decided I wanted to photograph for Transworld, even though I was in San Francisco. I photographed for them for probably a good solid four years, and could not photograph for any other magazine, unless I wanted to use a fake name. Then I got a call from Spike Jonze, who worked for World Industries and helped start Big Brother, and he asked me to photograph for that. At first I said no, because I would have to give up working for Transworld if I wanted to work for Big Brother, and it was a scary decision. Rocco’s magazine could have lasted for a year and then I’d have screwed up my relationship with Transworld, but I really wasn’t making that much of a living anyway.

Then I got a call from Spike Jonze, who worked for World Industries and helped start Big Brother, and he asked me to photograph for that…

I mean in 1992, when I decided to photograph for Big Brother, I lived in my car for a few weeks during that time. There was a recession all over the world and there really wasn’t a lot of work in skateboarding for photography and video. It was really difficult, financially, around that time, so I thought that if I wasn’t going to be making any money anyway, I’d just do what I wanted, so I said yes to Big Brother, even though it was this different new thing. So I called up Grant Brittain and told him I’d made a choice, and I was going to photograph for Big Brother. He offered me a little bit of money—a monthly retainer—but I had to try something different.

Big Brother didn’t really mind if a photographer worked for multiple magazines. I mean, they’d probably have used more of my photographs if I was able to only shoot for Big Brother, but after a while I was able to work for Transworld too. It became the case that if you had a sought-after photo, a magazine would run it. There were no contracts and nobody was paying me a salary. I lived in San Francisco until 1998, and I think that 1994 to 1998 was my most enjoyable time of taking photographs and making videos because I had freedom. I knew everyone, I could work seven days a week if I wanted to, and I was able to pay my bills and have a good time.

No Apologies for Cardiel appearance number 3 either. Rafter navigating Big Brother cover 1996 Photo: Tobin Yelland

Did Big Brother look after their people well? How was all that? You shot the Europe 1995 trip for them.

I remember that tour and the only financial talk I had with them about it was, “Can I go and will you buy me a plane ticket?” Then I’d buy it and they would reimburse me. I talked to Marc McKee and asked him for a thousand dollars, for expenses. For hotels and food and stuff like that. I had no idea how much things cost. Skate trips, from the very beginning, were all about all piling into one hotel room! So I got expenses paid, but as a skate photographer, advertisments were what paid the most. The magazines had their own rates and they could pay you whatever they wanted, but with advertisments you could kinda negotiate with the company little bit, so that was what paid the bills more than the magazines.

Was Deluxe not the place to be, for a San Francisco skate photographer?

Well Gabe started there in 1990, but I would still shoot some stuff for them, but it was always a conflict. I shot some Stereo ads, but with Anti Hero, I shot their first year so I had a little bit of a monthly cheque, just for shooting ads for that first year. But it was not cushy. Notoriously, Southern Californian companies would pay more than Northern Californian companies for skateboard photographs. Probably twice as much, in the 90s.

Why? Because that’s where Thrasher is?

Well Thrasher’s the older magazine and they started from nothing and made everything. They made trucks, wheels, a magazine, and eventually board companies, so I think they were more accustomed to knowing the rates. Forever we got $150 per advertisment, for so many years, while Dimitry Elyashkevich was getting $300 for Blind ads. I remember him coming to San Francisco and telling me how he didn’t need to work for the San Francisco companies because they were too cheap! Skate photographers being quite a small group helped us meet other people, like Dimitry, where you’d end up thinking, “Yeah, why am I charging $75 or $150 for this picture that they’re going to make so much more money off of?”

It’s crazy how these absolutely iconic photographs were only worth around a hundred bucks or so at the time.

Yeah. Time changes how something is valued for sure. Something from thirty years ago is cherished more, and if you look at a photo and get that feeling, that, “Yeah, that’s what it felt like!” feeling then it’s worth something.

What memories of Europe do you have?

I think my best memory, and it was so fucked when it happened, was through knowing Thomas Campbell. It was a 1993 tour and he introduced me to a Spanish magazine called 360, and the editor Francisco José Burgos, who flew me from San Francisco to Madrid, Spain. The first contest we were going to was in Münster, Germany, and so his plan was to drive from Madrid to Münster. I got in the van with all his riders from his shop or from his skate distribution company, and we seriously went through four vans before we got to Münster, and there were so many times when we were just sleeping in a broken-down van on the side of the road.

there were so many times when we were just sleeping in a broken-down van on the side of the road

It was insane. Once we got to Münster I linked up with the Deluxe team, which was Julien Stranger, Salman Agah, Jason Lee, Chris Pastras, and, I think, Kelly Bird, and I jumped in their van. I didn’t want to be riding in Francisco’s van anymore. It was intense, the drive from Spain to Münster.

So we cruised all around Germany after Münster, going to other demos and skate spots around Germany before going to England. I spent a lot of time with Jason and Chris, and that was the time they started asking if I’d be interested in filming a video for them, so we started talking about filming for the first Stereo video. That was awesome, but it was a funny situation because I’d been paid by the Spanish magazine to come out and photograph the contest—which I was going to do—but I just chose to jump out of their van and into my friends’ van. So suddenly I needed to pay for everything on my own, because I didn’t have Francisco there to buy my meals for me, and it was very challenging! It was normal to pile into a hotel room, but it was hard to have money to buy food and stuff.

When you took the job from the Spanish magazine, you must have known they’d be taking you out there to where all your friends were, right?

Yes. Yes. I saw Francisco at the different contests after that. I saw him at Northampton, and I photographed there and I gave him a lot of photographs of the contest. I think I also gave Big Brother photographs too. So I did give the photographs to both magazines.

That was good of you then, shooting enough to go round.

Not really, I was just trying to make money and succeed! Haha! Just trying to pay for expenses and film and shoot as many angles as possible because in ’93 I wasn’t that successful yet, I was just kinda scraping along.

We ended up going to Holland, and once the contests were over I was left out somewhere, and I’m not exactly sure where although it might have been England, and I needed to get back to Madrid to be able to fly home. I was lucky because there was a guy in Amsterdam—Frank Messmann who ended up being the CEO of World Industries after Rocco—who was friends with Francisco, or had done business with him, so this person was able to give me cash so I could buy a train ticket to Madrid. It was a crazy moment being out in Europe without a credit card, just with my passport, a camera bag, some clothes and a skateboard. It was a bit of an adventure to find this person, get some money and get a train back to Madrid.

Keith Hufnagel lipslides at Radlands. Photo: Tobin Yelland

The Anti Hero life, before Anti Hero.

Yeah. Figuring it out as you go along. It was a fun adventure. And that was a long train ride too! It was a solid twenty-four hour train ride but I saw so much great skateboarding and got so many great skate photos, especially in Northampton. Man, that contest was amazing. Tom Penny was exploding. I remember getting a really good photograph of Keith Hufnagel skating a barrier there in 1995; I don’t think it was even meant to be skated, it was a big plywood ledge.

The frontside lipslide.

Yeah, he did a lipslide on it! It was really hard to get the angle on it. I was looking down a long hallway to get that shot.

I’d gone with Ed Templeton and Toy Machine that year, and we got to go to Harrow skatepark. Thomas Campbell and Skin were there too, and I got a shoot a photo of Ed for the Welcome To Hell video cover. That was a really fun time. On another part of that tour I was with Alien Workshop and Karl Watson and Henry Sanchez were on the same tour, and we were in a big bus cruising all over the south of England, and we went to Cornwall. I have good memories of that trip.

Ed Templeton flipping the bird in Harrow. Photo: Tobin Yelland

That must have been a Profile trip. Profile was an underrated company. Who didn’t get the props they deserved?

There’s so much talent in skateboarding, but as with anything, the stars have to align. The stars have to align for you to be able to have a long career, and to film good video parts and things like that. You have to know the right people and you have to want it bad enough too. There’s a lot of people who didn’t make it as pro skateboarders who were just as good as big pro skateboarders. I know that for sure because I’ve photographed a lot of skateboarders.

I think one of my favourite pro skateboarders that only had one pro model is Brian Ferdinand. He’s a good friend of mine and he lives in Modesto now, but he lived in Castro Valley in the East Bay and I photographed him a lot.

Brian Ferdinand Mayday from 1989. Photo: Tobin Yelland

How is Coco Santiago doing?

I haven’t seen Coco in a long time. In the early nineties we would go skating and hang out all the time. From 1994-98 we lived two blocks away from each other and shot a lot of great photos together. Coco skated for Shut the Real the Black Label. The last photo we shot together was an ad for Black label. Coco is a nickname and his real name is Angel.

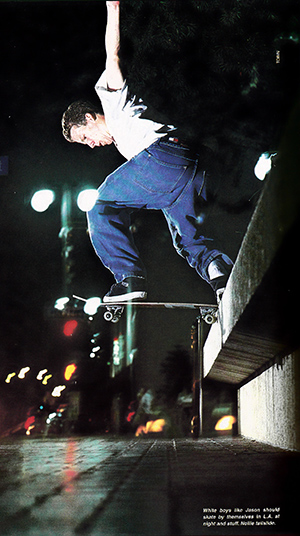

Coco Santiago Stalefish at China Banks. Photo: Tobin Yelland. Inset below – Jason Dill Nollie Backside Tailslide

Do photographers get on flow for film companies? I know there are people getting free cameras, but what about film?

Never when I was doing skateboarding work. That never happened to me or to anybody I know. I think it’s just always the magazine giving the photographer their film. It’s kinda like a sponsor. Actually, you know what, I think Ray Barbee got sponsored from Ilford, for some project.

I think that was a one-off promo thing, with Ray. So it’s not industry standard to call up the film company and tell them what you want?

No. There’s a really cool guy called Mark Whiteley who was a photographer who used to work at Slap magazine and now works at Apple, and he wrote an article called Rolling Through the Shadows all about how skate photographers use the Leica M6. Through that article we got to curate a photo show with Arto Saari, Greg Hunt and Thomas Campbell at the Leica gallery in Los Angeles, and through that I got to meet some of their marketing people and I got to try out some of their cameras. Just borrowing them for a couple of weeks at a time. So that was quite exciting for me because I love that brand so much. That’s probably the closest! Borrowing cameras and getting some discounts.

How much of Fucktards is a documentary of how those guys were actually living? Sean Young bombing the hill in the rain on acid, the projectile vomiting… Was that just what was going on?

Well the projectile vomiting is one of my favourite stories. Julien’s a photographer, and he takes great photographs. He’s always been good at drawing and at photography. I’m sure they’d been out skating that day, and they had the video camera with them when they were drinking at a friend’s house. They just kind of took over the kitchen, and I don’t know what Julien was expecting but he was definitely not expecting projectile vomiting. He set the camera up on the kitchen counter, and it just kind of happened. It was their friend’s house, but they were drunk and did not care if they threw up on the floor. Obviously.

I don’t know what Julien was expecting but he was definitely not expecting projectile vomiting

I love photography and I think about photography and how to capture photographs and video all the time, and the throwing-up is super disgusting but it’s also such an amazing example of positioning a camera and not knowing what’s going to happen, and then capturing something that’s really unexpected and crazy. I think a lot of people walk away from that video with that clip in their head. Like, “I just watched John Cardiel throw up?”, and it’s a solid stream of vomit. It’s so gross but such an amazing feat in cinematography and skateboard videos.

Haha! Well, yeah… There were always a lot of photos at China Banks and at Embarcadero, so was it hard work to find ways to make these spots look different?

On the subject of choosing different angles in general, I think it’s just a natural need—or want—to make and imagine from a different angle when you’re bored of the same angle. I love my 105mm lens, which is a telephoto lens, and I love just laying on the ground in the path of the skateboarder! If you’re far enough away where the skateboard is not going to hit you. Naturally in skateboarding you want to accentuate the height of the trick as much as possible, or I do anyway.

On the subject of choosing different angles in general, I think it’s just a natural need—or want—to make and imagine from a different angle when you’re bored of the same angle. I love my 105mm lens, which is a telephoto lens, and I love just laying on the ground in the path of the skateboarder! If you’re far enough away where the skateboard is not going to hit you. Naturally in skateboarding you want to accentuate the height of the trick as much as possible, or I do anyway.

In my kit I had a 105mm lens, a 35, a 24 and a 16, and I would just rotate them on the same trick. If I could. Just trying to get different angles of the same trick. Looking back on my photos now, I really like the natural light and lenses that weren’t really wide-angle.

I just lay on the ground. My favourite photos are me laying on the ground, whether it’s a fisheye lens or not. I think I got advice from some photo teacher to try to not rely on the 16mm so much, so I shot a lot of sequences with the 35 or the 24. Unless the 16 happened to be the perfect lens. Just trying to switch it up.

I think the most important thing is getting the trick. Everyone knows this, but making sure that if there’s a take-off and a landing, you show how dramatic and big that distance is. Sometimes you can’t get the angle you want because there’s something in the way, so you have to kinda work around it.

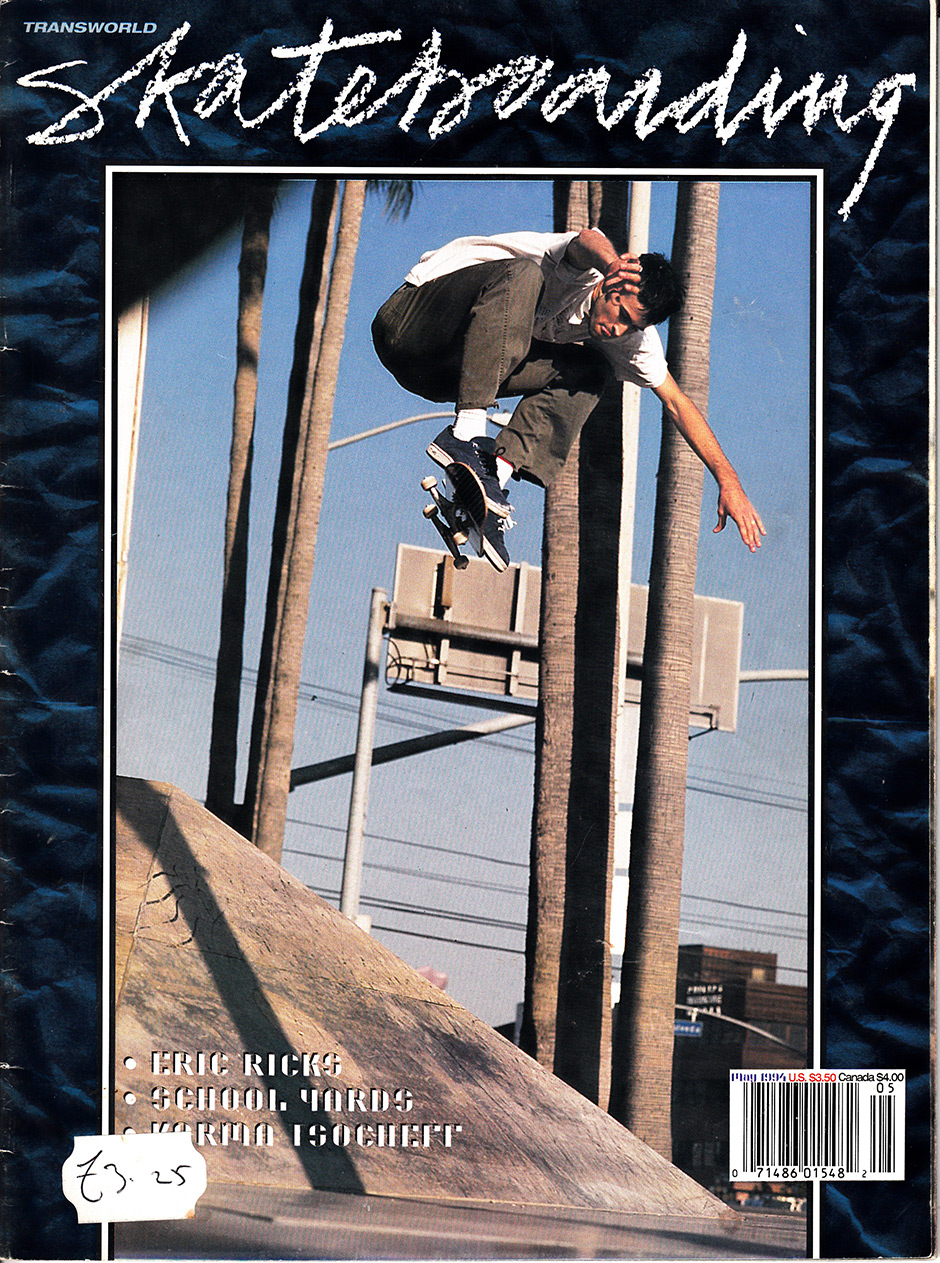

I was over on Santa Monica Boulevard yesterday where I shot Jason Lee’s big backside ollie photo that ended up as a cover for Transworld—and that bank is just a big planter now, with flowers growing there—and I was trying to remember what angle I got. It was really specific because there were light poles in the way, and I had to be on the opposite side of the street, and there were cars passing. I remember that I had to be between a wall and a light pole if I wanted it all in.

Jason Lee floating in Santa Monica in 1994. Photo: Tobin Yelland. Inset Below Tobin’s favourite issue of Big Brother

That’s a lot of choreography between you and Jason, if there’s traffic in the way and you’re somewhere awkward.

Yeah, but the skater is generally not really aware of cars coming and going, or when a car gets in front of the lens. You’re really just taking a chance that you don’t miss the trick because there’s a car in the way, so you have to keep shooting until you get it.

How long did that one take?

Probably an hour, or a couple of hours. I know we got kicked out of there a lot, so I can’t remember if we had to come back a couple of times, but that was a fun spot.

There’s a lot of long lens skateboard photography right now, but using it differently to how you did. Sometimes it can take a second to see where the skateboarder is in the frame, amongst the traffic and street furniture, especially in the European magazines. Do you like that stuff?

Oh, I love that. I have a favourite photo that Jai Tanju took, which I think was in Slap magazine, and it’s of someone doing a manual and Jai’s shooting into the sun. The skater is really tiny. It’s really cool. Photographs and drawings, anything like that, are made to communicate a feeling, so it’s really cool to see images with different composition, colour or techniques. I love all different vantage points, but I guess as a photographer you kinda want to cover all the bases. If it’s a gnarly trick you really want to show how hard it is to do that trick, but then the more artsy kind of photographs are really fun to do too. It’s fun to try out all different compositions.

Have you got a favourite issue of a skateboard magazine?

Have you got a favourite issue of a skateboard magazine?

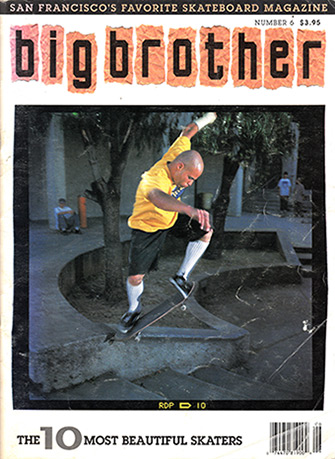

I like the issue of Big Brother where it’s kind of bigger, and Salman Agah is on the cover doing a switch backside tailslide.

Issue six, the cereal box one.

Yeah. There was a lot of silly, silly photographs in that. I think the contents page was my friend Brian [Ferdinand] peeing off a roof, standing next to Julien who was looking down at the crowds of people walking by on Market Street. There were a lot of good skate photos in that too. Another issue I like, and I’m not sure of the number of it, was a Transworld that I got my first photo in. It’s a double-page spread of Jef Whitehead —you can look up on Instagram, he’s an amazing tattoo artist and painter and he’s @wrestplague on there—and Mic-E Reyes in the back of a police car. Mic-E’s laughing and Jef’s just kinda going, “Huh?” That issue’s one of my favourite magazines because it’s quite exciting, as a photographer, to be published, and oftentimes it’s a surprise.

Speaking of Mic-E… You lived with him and once mentioned him shooting a gun in the house. Jeff Pang mentioned Mic-E shooting a gun in the house too, so was Mic-E just always firing guns in the house?

I think it probably just happened a couple of times, and Jeff just happened to be there for it one of those times. It wasn’t a daily thing. One of the times, I knew it was going to happen. We lived in a huge warehouse, so it wasn’t like a normal house with normal neighbours or anything. We had a darkroom, there was stuff everywhere—bikes, skateboards, all kinds of junk—and there were these very thick wooden beams that if you shot a gun into, the bullet would just stick into it. It wouldn’t go anywhere. Those were some wild times.

Have you ever been disappointed by how a photo’s been laid out, or captioned or anything like that?

Probably. But by nature, I’m not super picky about art direction and things like that. I don’t overthink it and I don’t really try to control it. I don’t try to control how my photographs are printed or used or anything like that.

There was one time I got super pissed off about how a magazine did not credit me for a photograph. I think I was just in a bad mood already, but it was when Skateboarder magazine started coming out again, and Thomas Campbell was the editor. I had shot a sequence of Brad Staba, and for me, I felt like it was one of the best things I had done that year. It was a fountain in downtown San Francisco, and it was a high-to-low gap with a big waterfall in the way.

Oh yeah, from his part in Duty Now For The Future.

It was downtown, at City Hall, and it was a total bust so we didn’t think about staying long, so it was a huge victory to get those photographs. It could have been used as an advertisment, which would have been better, but it was used for the contents page of Skateboarder magazine and I wasn’t given photo credit. It was mis-credited and Thomas Campbell was given photo credit instead, and he was the photo editor. I was in a grumpy mood anyway but I was so pissed off. It sucked to not get credit for that because I’m a freelance photographer and every image that’s good and has my name on it is a calling card for my next job. That’s the only time I can remember.

Did you speak to Thomas?

I think he was out of town and someone else put the credit on. I know Thomas didn’t put his own name on my photo. I think the issue was almost done and that credit hadn’t been typed in, so someone else thought that he’d shot it.

Who would you shoot with that you’d always know you’d get a photo?

Back when I was shooting every day, the most consistent skaters were Ethan Fowler, Julien Stranger and John Cardiel. They were always on a mission to get photos, always going above and beyond. Also Sean Young; I’ve got a lot of good photos of Sean Young. He was always really relaxed and he was always livin’ in the moment. Chris Pastras was really fun to shoot too, he would always figure out new spots to go to. It really depends, because the moment in a skateboarder’s life when they’re easiest to photograph is when they’re hungry. Hungry to get work done. Getting your video part done is obviously more important than stills, but just to go out and shoot with someone who’s super motivated.

Simon Evans step-off 180. Photo: Tobin Yelland

Which UK people have you enjoyed shooting with, or just spending time with?

Simon Evans was always really fun to shoot, and I really liked hanging out with Simon. He used to work in a tea shop right off Church Street in San Francisco, and I used to visit him in there. He’s really thoughtful.

I really like the step-off 180 that we shot. Earl Parker was holding the flash for that.

There’s a photo of him at Wallenberg that I really like, of a switch 180 nosegrind. I shot it with a 16mm macro lens and I wasn’t expecting it to be in focus because it has a very shallow depth of field but I really love how that photo came out.

I shot it with a 16mm macro lens and I wasn’t expecting it to be in focus because it has a very shallow depth of field but I really love how that photo came out

Simon Evans Switch 180 nosegrind at Wallenberg. Photo: Tobin Yelland

Carl Shipman is amazing, of course, and we had a lot of fun times together travelling. We kinda buddied-up and travelled from England to Germany had a really fun adventure making that journey. I’ve got a lot of good skate photos of Carl that we made.

Also Paul Shier. I went to Paul’s house with Simon, in England, and although I didn’t shoot with him much we got some good photos together.

Then there’s Bob Boyle; I got some great photos of Bod Boyle back in the day. I was neighbours with Bod Boyle for the last ten years, and it was always fun to see him around. He’d often be with Steve Douglas too.

Chilling with Carl Shipman in Cornwall. Photo: Tobin Yelland

You shot Jagger too, in Chicago.

Oh, of course! Jagger’s another one. I first met Jagger in San Francisco when he came out here. He’d saved money to get here, and he stayed in San Francisco for a long time. We used to go on trips together, and I brought him up to Auburn to skate with Cardiel. I also drove Julien and Jagger down to Los Angeles one time, and we hung out at Natas’s house at Venice. A memory of Jagger I’ll always have was from 1992, I think, and our living room had a couch in it, a fold-up couch that rolled out into a bed… We were goofing off, and I think he may have fallen asleep on it but I remember Julien folded him up in the coach and Joey and Wheat Berry [Jesse Driggs] were all jumping on the folded up couch. I don’t think he was hurt but I can’t get that memory out of my head.

Also, I have photographs of Jagger after he’d got hit by a car. He was bombing down Haight Street, crossing Divisadero, and if you’ve ever gone down that hill you’ll know that it’s a kind of blind intersection. The light had turned red but I think he decided to go anyway, and he got hit by a VW Bug. He had a black eye and a big scrape on his head but he was OK.

Then I saw him in Chicago and he didn’t want me to call him Jagger. I think he’d befriended a bunch of new friends and he decided that his name wasn’t Jagger. “OK Dan. Cool, Dan”. I got a good photo of him doing a wallie off an elevated subway line. He was a really good skater.

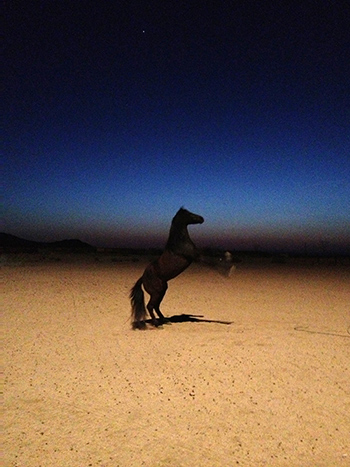

Dan “Jagger” Ball wallie in Chicago. Photo: Tobin Yelland. Inset Below – Horse shot by Ivory Serra

Have you shot much skateboarding for non-skate projects? There’s a lot of skateboarding in commercial projects right now, and it’s not all very great.

It’s not all great. But yeah, I have a little bit. Most recently, I think about four years ago, I shot Justin Bieber skateboarding for Calvin Klein. It was just a 45-minute miniramp session where I had to get as many photos as I could. That’s one of the most memorable ones.

He can kinda skate, too. He seems to genuinely be into it.

You know, he just loves skateboarding. I don’t know him at all but I know that he loves skateboarding. He was doing a whole day’s shoot, where it was more studio shots and they were shooting on all film. That’s why I was hired for it, because they’d seen some examples of my film work in some zines and they wanted to make a zine of him, of portraits and skate photos. We had some ideas of places to skate but he wanted to skate a Brooklyn projects miniramp close by, so Mike O’Meally and I skated down there and met him—Mike was assisting me—took photos and I could tell he really liked skateboarding.

What’s the strangest place a photo of yours has shown up?

One of the strangest places was on magnets for Tylenol, the pain medicine. Another non-skate company I worked for! It wasn’t quite skate photos they wanted though, they wanted pictures of people in pain. I had a photograph of Dan Drehobl doing a kickflip down 18th Street in San Francisco, and it was a really hard trick so he had fallen a bunch of times, but he has a really upbeat attitude about falling and getting hurt. He’d fallen and he was kinda laughing, and doing a push-up off the ground, so it was a weird to have that on a refrigerator magnet.

Street photography is everywhere now, because everybody has a camera in their pocket and an Instagram account, but how has it changed since somebody like Martin Parr was doing it? Is it easier or harder now that it’s so normal?

I don’t know. I don’t do a lot of street photography but I love thinking about street photography because anyone who likes to take photographs will notice cool things just happening in front of you. If you’re a photographer and you see something that would make a good picture, you’re immediately thinking, “Where’s my camera?”, or how to capture the image. I love Martin Parr and I’m always placing myself in the photographer’s position when I look at photographs, especially with street photography, and wondering how they got that shot.

Street photography takes a lot of courage. You get a lot of reaction from people not wanting to get their picture taken, I’m sure. I think it’s the hardest type of photography because nothing about it is set up, you’re not combining all the elements to make what you want, it’s just you photographing what’s there and making it your shot.

I think it’s a double-edged sword. It’s nice that there are cameras everywhere, but that just means that there’s more photographs in the world, and I think that would mean it’s less special. We just look at so many photographs today. It’s awesome that it’s so quick, and you can see it on Instagram and stuff, but there’s just a lot out there.

There are different types of still photographers too; there’s fine art photographers and there’s the more kind of internet-photographers. It’s kind of all blurring together but it’s all progression. If it’s creating something new, that’s great.

Do you think digital can have a heritage, beyond people filming with VXs? Will people soon be seeking out ten year old iPhones to film and shoot with?

I would think so. Every camera gives a different look, right? I like the first Canon 5D. The first 5D didn’t have video on it, it’s 12 megapixels and the resolution is noticeably different from the 5D Mark 2. When the 5D Mark 2 came out, you wanted that higher resolution and that crispier photograph, but there’s something unique about that first 5D and its 12 megapixels. I feel like it’s up to you, what you like, and also as a photographer you’re looking for equipment to set you apart from other people because you want to create something unique.

If you’re in a group of people and they’re all taking pictures, and they’re all amazing, then you’re searching for a look that’s exciting to you. There are just so many damn cameras out there to use and there are some awesome ones, but I think the cameras that no-one gives a shit about today will be sought after tomorrow. It just goes like that, people are always looking for something that’s unique.

If you’re in a group of people and they’re all taking pictures, and they’re all amazing, then you’re searching for a look that’s exciting to you. There are just so many damn cameras out there to use and there are some awesome ones, but I think the cameras that no-one gives a shit about today will be sought after tomorrow. It just goes like that, people are always looking for something that’s unique.

I think it’s fun, and if you’re putting a project together you probably want your project to be unique, and there’s so many cameras that people aren’t using that means you could be the first person to do your video in that way.

I have a friend named Matt Kennedy who does motion picture stills, and he’s my age, and his teenage son who skates is getting into skateboard film-making. I remember him asking me about what camera is the one to get him, but I think his son was more interested in the VX. Each camera has a look and it’s about whatever look excites you. The best camera is the one you have on you. You’re carrying it with you because you’re excited about using it so I don’t think it really matters what type of camera it is. I’ve seen some great photographs on iPhones. My friend Ivory Serra’s an amazing photographer and skateboarder, and one of his latest printed zines has a wild mustang horse rearing up on its back feet on the cover and it was lit by a flair, at night. It’s a beautiful black and white photograph but that’s an original colour image that he shot on his iPhone. It’s an amazing photograph, where it doesn’t matter what gear he used.

What’s the best way to get good at shooting photos? Shoot everything, right?

Yes. Shooting a ton. Shooting a lot of photographs is the best way to get better at being a photographer, for sure. Also looking at a lot of different images, and not just photographs. You might even get more inspiration from looking at painters than looking at photographers.

Shooting a lot of photographs is the best way to get better at being a photographer, for sure. Also looking at a lot of different images, and not just photographs. You might even get more inspiration from looking at painters than looking at photographers

I had some good advice from an Italian photographer I like called Lele Saveri, and his technique for getting inspiration is going to thrift stores and looking at old magazines or books that have a lot of photographs in them. He says that’s his favourite way to get inspired. He compared it to a photographer who only looks at contemporary books, because there is a certain amount of envy or excitement that you feel when you see someone make a great photo, but he thought that if you only look at contemporary images you’ll tend to make images that are similar just because that’s all you’re looking at.

I have another friend named Dave Carnie who was originally a photographer but who does all sorts of stuff, and he would be inspired by paintings of Greek tragedy and all those ancient themes. He would find those images in books and then recreate them in photographs, then he’d print them and dye the paper or work with charcoal on the print to make his own thing. I thought that was really cool.

Chris Carter stitches up fred gall in the UK. Photos: Tobin Yelland

I’d have thought there’d be a documentary about 90s West Coast skateboarding by now. The East has a couple, surely there’s movie waiting to be made.

I imagine there is. I think ‘90s skateboarding in general is the golden age of skateboarding. When Dogtown, and the Z-Boys, were around, that was a golden age too but in the ‘90s there was a big shift. The freshness, and the shift from vert skating to street skating just opened up the doors for so many kids to skate in their towns. So much happened.

So much of the best stuff is on film, and I think a lot of the people involved would be available to talk about it. It seems like something Deluxe would do, but I dunno.

I think Deluxe has their hands full. I think any skateboard company has their hands full just keeping the ball in the air, just keeping in business. There are so many ups and downs so a big documentary would be a huge endeavour. It’s expensive too. But someone has to do it, you’re right.

What are your plans for the rest of the year?

Right now my kids are starting school. I have an eight year-old daughter and a thirteen year-old son, and this is the first week of school so we’re all getting used to being on computers and having school at home. I haven’t really been shooting as much as I would like to, because of Covid, but I’ve done some portraits of friends. I’m on hold to see if I get some advertising jobs, but there aren’t many films that are shooting. I’m mostly working on my skate archive. I’ve got a new Instagram called @tobinshop, that’s just skate photos, and that connects to my shop. You don’t have to buy anything, you can just go check it out, it’s tobinshop.com and I have over 150 now, but my goal is to have at least 250 images because that’s how much the website will hold.

There’s a whole load of stuff on there that I’d never seen before.

That’s my goal. They’re not all cover shots and they’re not all names you’d recognise, but I like that. There’s a lot of people that I have great photographs of that weren’t pro skateboarders, and it’s really fun to share those images, because they were shot twenty or thirty years ago.

I just spoke to a woman who was looking for a photo of her husband, since I’d shot photos of his miniramp when he was just a teenager, and that was for a surprise birthday present. It took a long time to find the picture because I didn’t know his name at the time, but I’d written ‘Ramp Owner’ on the slide so I knew it was him. She got in touch because she saw a photo of her husband’s ramp on my Instagram so she wondered if there might be a photograph of her husband too.

I’m just excited to be able to share my photographs with anybody who’s interested in seeing something that they don’t see on my website. Please email me through tobinshop.com

You’re about to get a lot of emails.

Yeah! I hope so!

We massively appreciate Tobin taking time out of his busy family life to talk to us and share stories about his incredible contribution to our culture. We thank him for the photos he sent us and for being out there to capture golden moments imprinted on our brains. Additional mag scans courtesy of @ScienceVersusLife

Previous interviews by Neil Macdonald: Carl Shipman / Corey Duffel / Eli Morgan Gesner / Jeff Pang.

More photo stories: Andrew James Peters: Mentors, Heroes & Monster Children / LIGHTBOX: Gino Iannucci by Ben Colen / LIGHTBOX: Karl Watson by Mike Blabac / Seu Trinh: Creative Destruction