We are proud to bring you an exclusive Eli Morgan Gesner interview. This in-depth conversation is a trip back through New York skateboarding history…

Words and interview by Neil Macdonald (Science Vs.Life). Eli Morgan Gesner in NYC

While it’s one thing to be in the right place at the right time, it’s another thing all together to be part of establishing just why that place and time were so right. Eli Morgan Gesner was born in New York City to liberal, artistic parents and although he knew the Upper West Side as home, it was the decrepitude—and the artistic open mindedness—of the city’s Lower East Side that fuelled his enthusiasm for the graffiti he’d see on walls, doorways and eventually trains as mayor Ed Koch dragged the struggling city into the 1980s amidst genuine bankruptcy fears and an alarming heroin epidemic. As businesses closed and whole areas become no-go zones for regular people, the artistic underground could flourish, with punk rock, hip-hop, graffiti, and soon enough, skateboarding all taking over the crumbling district, and Eli immersed himself in it all.

From witnessing these changes first hand, and having the freedom to explore them and meet those involved, it’s understandable that Eli would end up making his mark, literally and figuratively, on skateboarding, clothing and art. Through skating and drawing for NYC OGs Shut, to being a vital part of the founding of Zoo York and the creator of its visual aesthetic, inadvertently helping start the idea of ‘streetwear’ via work with Shawn Stüssy and Def Jam’s Russell Simmons, to licensing confusions and global marketing meetings, cargo jorts and now, finally, a regained ownership of the skateboard brand that put the East Coast on the map, it’s obvious that Eli has a story to be told, so I called him up to hear it.

You’re born and bred New York City, right? How did you find skateboarding?

I was born here in 1970. The playground I grew up playing in, right across the street from where I was born, is the playground in the movie The Warriors, where the gangs all meet. I saw them shooting it. So things like that have taken on a significance of their own, but when you grow up there it’s just your neighbourhood.

As far as skateboarding, I saw people here and there but back then it was kind of ‘exotic’. I was into disco when I was six or seven years old, and in Central Park there’s this place called The Flats, where they had a rollerskating rink where all the kids my age would rollerskate around to disco music with all the rest of the people. There were guys there who’d been skateboarding since the ‘70s doing downhill slalom, so they had the course set up, with the cones, and the rollerskaters and the skateboarders would just do the slalom. Everybody would watch. You’d get a giant crowd and everybody would go faster and faster… Woosh woosh woosh through the cones. So that was the first time I saw skateboarding, but I wasn’t really taken with the idea of doing slalom. Haha!

It was the Pepsi TV commercials and the early movies that did it. I guess on the West Coast they’d started building concrete skateparks around then too, so that all kind of sparked my interest in skateboarding because it looked so cool. Even just the location of a skatepark, and all the weird concrete shapes; the banks, the waves, the bowls, all that was completely unlike anything we had in New York. And the sun was always out in the commercials, and they had palm trees, so there was that appeal, but where are you going to do that in New York?

As I got older I got into writing graffiti, because that was what was really cool. So when I was nine or ten years old, around 1979, 1980, I started doing tags.

So where did you live? Where were you hanging out?

I was living with my mom on the Upper West Side, on 95th and West End Avenue, off Broadway. That was where I kinda got into everything. The other thing that was going on at the time was the whole ‘Downtown’ scene, the punk rock, new-wave, kinda hip-hop thing was happening. So nowadays when you come to New York and go down to SoHo or TriBeCa, it’s an established location. When I was a kid everything south of about 14th Street was industrial units, warehouses and trade places. You’d go there to rent paint supplies, or rent a forklift.

It wasn’t a residential area but in the early ‘80s, all the artists moved down there and into the warehouses, so the Downtown ‘80s art scene started popping off, and all the music was down there. CBGB’s was down there, and all the cool nightclubs were down there, so even when I was a little kid my mom—who was a cool mom—would take me and my sister down to SoHo and we’d walk around 8th Street, and you could feel this energy. The ‘80s skate boom was about to happen, but again, I was in New York and operating under the idea that that was a Californian thing, it was a colloquial activity only for people in California, so it wasn’t something that I was really aware of.

In the ‘70s, in my neighbourhood, that’s where the Soul Artists of Zoo York were born and formed. That was Marc Edmonds who wrote ‘ALI’, Futura 2000, and a skater named Andy Kessler, so it was this graffiti crew that had a skateboarding component. The graffiti writers Haze and Zephyr were involved and used to skateboard, and Puppet Head too. So I would see those guys in my neighbourhood skating a quarterpipe, but I didn’t really know any of those guys well enough and they were so much older than me, I was just a child. I would have had to be friends with a younger brother of one of those guys to get into that circle, so that never really happened for me.

Were those guys just regular dudes at this point, or were you in awe of them?

Oh I was in awe of them. There’s nothing that’s even comparable nowadays. Nowadays if you want to get into skateboarding, it’s on the internet or you can go down to your local skatepark. It’s readily available. But this was a really rare, exotic activity. So the park I mentioned, where they shot that scene for Warriors, right behind that park is this asphalt runway that’s right next to the Westside Highway, and then the Westside Highway is adjacent to the Hudson River.

In the ‘70s they were doing construction work on the highway and they built these walls to keep people from going into the highway, and they were painted green. The skaters dismantled the plywood and built a quarterpipe on the roadway behind the park, and even before I saw people skating it, just from being a little kid running around, I would see this cobbled-together ten foot quarterpipe and be like, “What is this?! Is this a slide? Am I supposed to play on it?” and we just didn’t understand. It had early graffiti tags on it too.

Quarter Pipe on the Elevated Westside Highway

I’ve seen a picture of that thing, I know what you’re talking about.

Right. So we go over there with my mom and there’s a crew of guys just doing kickturns on the quarterpipe, like it was in the ‘70s. I must have been about six when I saw that going on, and I remember watching it, and not knowing what was going on. It was clearly not the circus, it was just a bunch of guys. Also at the time in New York, dudes would go out on the street and play bongos, or juggle. Shit like that, you know? So maybe you’d think that these guys are street performers or something, but what they’re doing is fascinating. I think I had a little board, a Zip Zinger type of thing back then, but I couldn’t stand on it and it really wasn’t my thing.

It was around 1981 or 1982 that I really got into skating, when I was writing graffiti. The original Zoo York crew had disbanded, or got real jobs, and the younger kids who were writing graffiti in the Upper West Side—who I hung out with—all skateboarded. They all had skateboards, so they kinda made me get a real skateboard. I saved up my money and went down to Dream Wheels in SoHo, which was right off of 8th Street, and in the ‘80s, in the new-wave ‘80s when Madonna and Run DMC were coming up, 8th Street was like the coolest place in New York City. Everyone in the whole city would come to go shopping there. The whole street was just a shopping street and you’d go there to buy cool shoes and cool clothes, and all the cool music was there.

All that stuff that made up a kind of ‘community shopping street’ of the sort that is dying out in America now because of things like Amazon. So I got my skateboard, and I was skating around with the crew as the young little kid who was just starting out. Another good thing about being a skateboarder back then was that nobody skateboarded. So if somebody saw you with a skateboard, and they knew about skateboarding, they would run up to you and strike up a conversation. That’s not something you thought about at the time, it was just, “I want a skateboard, and I’m going to learn to skate”. It wasn’t about making friends and meeting people, but lo and behold, if you’ve got a skateboard and you go skating with your buddy in Central Park you’ll run into another three kids skateboarding.

Of course.

So the first time I met the official ‘gang’ of local New York skaters was the day that I bought my first skateboard from Dream Wheels. I got a kind of entrée to Dream Wheels because I was a really good graffiti artist. I could draw really well from a young age, I had a lot of drawings and stuff with me, and when I went in there, they had graffiti art on the window. So I showed them my art, and they figured that I wasn’t just some regular kid going in to get a skateboard. They thought I was skilled I guess, so they took me under their wing.

What were you writing?

I was writing ‘NOST’. I had a little name for a little while, but it was only up in the Upper West Side. I wasn’t really bombing around the whole city. I was a little kid, but the thing I used to compensate for my inability to sneak out of my mom’s house and go bombing all the time was that I could draw really good, so I would hang out with the older graffiti writers and do letters for them, or characters for them. So that was my little ‘in’ with all the established graffiti writers, and in my head I didn’t think that graffiti was ever going to stop.

In my head graffiti was something I could train for when I was older because I grew up seeing graffiti on trains my whole life. Why would it end? Back in 1982 I was this tiny little kid, if I ever got caught or got into beef I would have to run or get my ass kicked, but I thought that if I just kept going, then by the time I was 18 or 19 I’d be doing trains, but I got distracted by skateboarding.

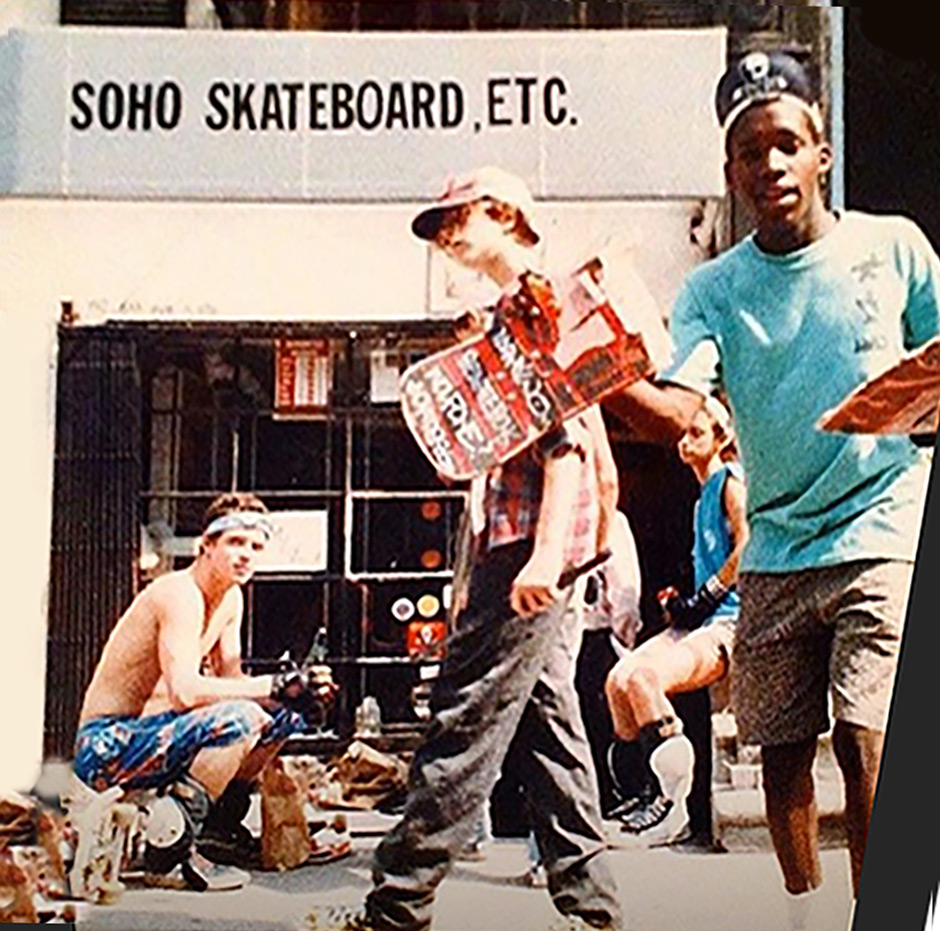

Ian Frahm outside Soho Skates

The best guy I saw on my first day out skateboarding was this guy Ian Frahm. He was a punk rock, new-wave graffiti-writer skateboarder. He wrote ‘THOR’ and IBM was his crew. He had fame, so I thought that because we were both into skateboarding as well, that he’d be my buddy, and he was just like, “Fuck you, kid”. Haha! He was part of the original group of New York downtown skaters from the ‘80s, with Bruno Musso who started Shut skateboards with Rodney Smith and Big Jim who’s a famous New York City presence, that whole era of guys who were kind of paving the way for me and the younger kids who were maybe just about to get into High School. To really succeed at graffiti you have to be out all night sneaking around, which I did, but it’s difficult, especially when you’re twelve and you live with your mom and have to get up for school the next morning. It’s a problem. With skateboarding, I could take my skateboard with me on the subway or to school, and I could skate around after school so skating just slowly seemed to take up more and more of my time. I started meeting more people who skateboarded and had all the same interests.

I vividly remember meeting Alyasha Owerka-Moore when I was a kid and he was just like me but from Brooklyn. He and I later went on to start Phat Farm, with Russell Simmons, but at the time we were just two kids who skateboarded and wrote graffiti. So I really took to skateboarding and got good at it pretty quickly. One of the funny things about humans, and our whole culture in general—especially around things like skateboarding and sports— is that there’s always this oneupmanship that happens when the new generation comes in and pushes it to a level you’d never have thought possible. When I first started skateboarding, all the older skateboarders were the ones who grew up in the ’70s doing slalom, so the idea of doing a skateboard trick, like a flat ground boneless, was advanced stuff for them. “Wait, you step off the board, then jump back on it?” They were doing Bertlemans, you know?

So when I started skating, they were all trying to learn how to do bonelesses. So they’re trying to expand on years and years of skate experience and trying to figure out how you take your foot off and where to grab the board, but that was day one for me. Day one for me was outside in the front of my building learning frontside 180 bonelesses, and then it was frontside 360 bonelesses within a week. So the next weekend I’m out and I’m doing these bonelesses and they’re like, “What the fuck?! You’re a skate prodigy!” So the dudes who showed me the 180 boneless saw what I was doing and they took me to the shop, to Larry and Jeff’s, a bike shop that sold skateboards. I think it was actually Bruno who was working there, so they told me to show him and I was just doing it down some steps. They thought it was amazing.

So I went from being a kid skating on my block to hanging out with all the best skaters in New York City because I learned how to do a frontside 360 boneless. This was before the ollie. We didn’t understand ollies. We would go to Washington Square Park and there were little benches that we’d do boneless onto, and jump off, or do sweepers, or a boneless to tail, but slowly the ollie started emerging. It was a whole process for everybody to learn. Everybody was trying to ollie a board on its side, and that was a whole year-long process of figuring out how to get the board in the air, how to get it over the board, and keep it straight.

So I went from being a kid skating on my block to hanging out with all the best skaters in New York City because I learned how to do a frontside 360 boneless

Where had you guys seen an ollie back then?

When the graffiti writers in my hood told me I had to get a skateboard. They were these black and Puerto Rican kids, and they had one ‘white kid’, although he was of Spanish heritage, and his name was Ben Alvarez. Ben Alvarez was immediately different from everybody when I first saw him because he wasn’t a hip-hop guy, he was a punk rock dude. Like a new-wave punk rock guy who had the full outfit of the overcoat, the chukkas, the Ramones t-shirt and the haircut, and when he talked he had a Southern accent because he was from North Carolina. Ben had to move from North Carolina to be in New York City with his mom, but back home he had a skateboard ramp in his back yard, so he was a vert skater. He showed up in the Upper West Side in 1980, this punk rock skateboard kid, so all the graffiti writers who skateboarded ended up hanging out with him.

There was this little concrete loading ramp going up to a door, this wheelchair slope thing, not even a bank, and I remember watching him borrow s omeone’s board and skate up it, and do this scooper 180 ollie to stop. And then just slowly roll back down. We were amazed and he was all, “Yeeeeah, it’s called an ollie pop, and it’s like doing a frontside air without grabbing the board”. That was the first one I saw but for the older guys it was so advanced that it didn’t even register. Like it was such advanced skateboarding that these graffiti/skateboard guys weren’t even going to talk to him about it, but I was a dumb little kid and I needed to know everything about it. That was almost like the one advantage I had over all the guys downtown.

I was going to the Elizabeth Irwin school, the Little Red School House down in SoHo, so every day I would take the subway down to SoHo, then after school I’d skate with all the Downtown kids, then get the train home at rush hour to have dinner with my mom and do my homework, and then I’d go skate with Ben. Ben was the first person in New York City to do an ollie. Ben and I would spend all night learning ollies, trying frontside 180 ollies because this was before boards had noses. Like a Natas board with a one inch nose.

Like pushing a powerslide through the air.

Exactly. Ben had the ramp skating skills, but he had to figure out how to skate New York. This ultimately led to Ben coming up to me one day and saying, “Dude, there’s this place under the Brooklyn Bridge… It’s like a giant wave!” So we made our first journey down to the Brooklyn Bridge banks, which I think was a bit of a well-kept secret. There was still territoriality, that kind of ‘locals only’ vibe, and even though I was skating with all these dudes in Washington Square Park, they were not going out of their way to tell me that there was this giant skatepark underneath the Brooklyn Bridge. Haha! So Ben found it on his own, on the off ramp of the Brooklyn Bridge. So it was like, “Oh my God, we have to run across the fuckin’ highway?!”

Obviously now it’s a legendary skate spot but when we first got there it was like this forgotten corner of New York. First of all, it was filthy. It was just covered in garbage and trash from people throwing things from their cars on the bridge. And it was new. The bricks were all laid out so perfectly, these square-edged bricks. They weren’t sculpted bricks, like when they’ve been moulded, it was more like they’d laid out a huge sheet of brick material and then cut it with blades, so the bricks were really sharp on the edges. It was really hard to skate. If you tried a powerslide, half the time the board would get ripped out from underneath you because the edges of the bricks were so sharp. It would take years and years and years of people skating the Brooklyn Bridge banks to wear down the bricks to where it was good for skateboarding.

That’s pretty East Coast. People don’t normally need to wear the ground in…

We were making it up as we were going along, so there was nobody there to say that the bricks were too sharp. We just kept skating, trying inverts because inverts were really popular. Another thing that people don’t know about the early days of the Brooklyn Bridge banks, is that the wall where everybody sets up to do their tricks? That background wall you’ve seen in videos a million times, actually used to be open. So underneath the Brooklyn Bridge, there used to be where they would store hotdog carts and things like that. The police would store stuff there too. And it was just an old wooden barn door; it was almost like one of the last things left in the city from the early 1900s. You could open up the door and get in, and it was just this homeless shit show. It was so gnarly.

There was this gang of homeless black guys who lived in there and they had tapped into the streetlights outside and had wires running into this giant cavernous space back there. It was scary and they didn’t like us. Their wires would be going across the banks, and we’d rip the wires out to skate so they’d come running out and throw bottles at us because we fucked up their house. There was also this huge infestation of rats. The rat problem in New York City’s gone down a lot but back then there were these giant, foot-long rats running everywhere. So it wasn’t just the skaters at the Brooklyn banks, there were the homeless people who hated us, then there was the rats, and there was also a gang of Puerto Rican and black BMXers who lived over on the projects and they hated us too, so it meant that when you wanted to skate the banks you’d have to get as many people together as you could to head down with. It wasn’t always like that, sometimes it was mad chill, but there was definitely a problem with the homeless guys. What was that Bones Brigade video..?

Future Primitive.

Yeah, where they come to New York. You can see some of the old barn doors in that. Ian is in that video doing an ollie up onto the small wall. And Dante Ross! This huge multi-Grammy-award-winning music producer and legendary New York City thug sitting watching the Bones Brigade. Haha!

By the time this video came out the city had kicked out all the homeless guys, and they’d realised that by leaving these giant halls underneath Brooklyn Bridge banks they’d just attract unwanted people and shit like that, so the city closed it all off. They bricked it up so you couldn’t get inside. Once that happened it made it much easier to go skateboarding at the banks, and the whole crew would start to meet there.

This huge multi-Grammy-award-winning music producer and legendary New York City thug sitting watching the Bones Brigade

Brooklyn Banks session in progress. Photo: Carolyn Owerka

How many of the crew were natives and how many were travelling in from elsewhere?

It was a small crew. I think in total there was maybe around 30-40 of us who all lived across Manhattan and in some parts of Brooklyn, and we would all hang out in Washington Square Park. That was kind of our headquarters. Before the internet and before cellphones you would get up, get on the subway, and go down to Washington Square Park and hope you would run into somebody. There was usually always someone there to skate with, but if there wasn’t sooner or later someone would show up. So we all knew each other.

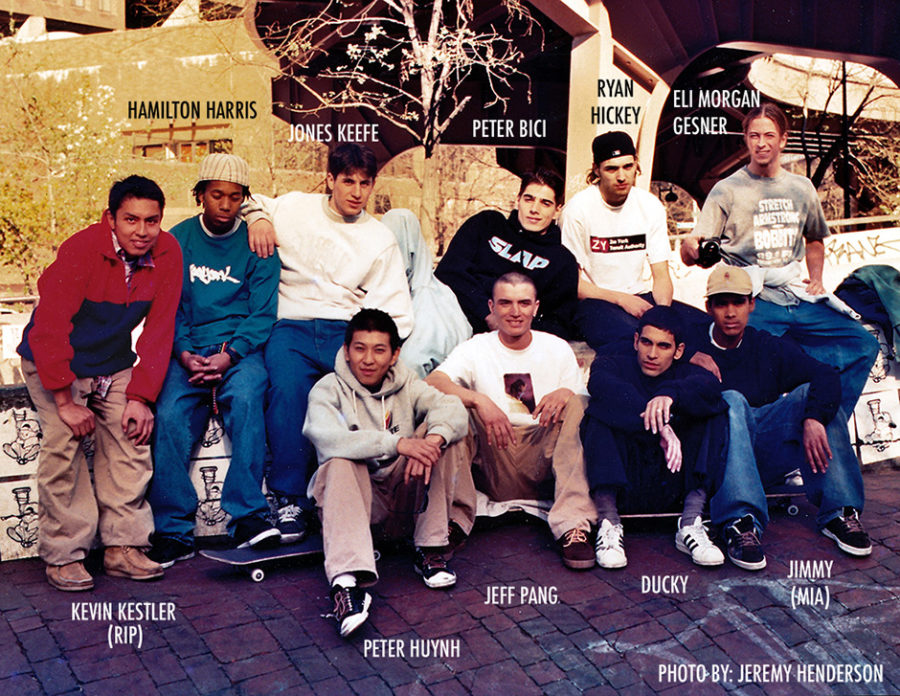

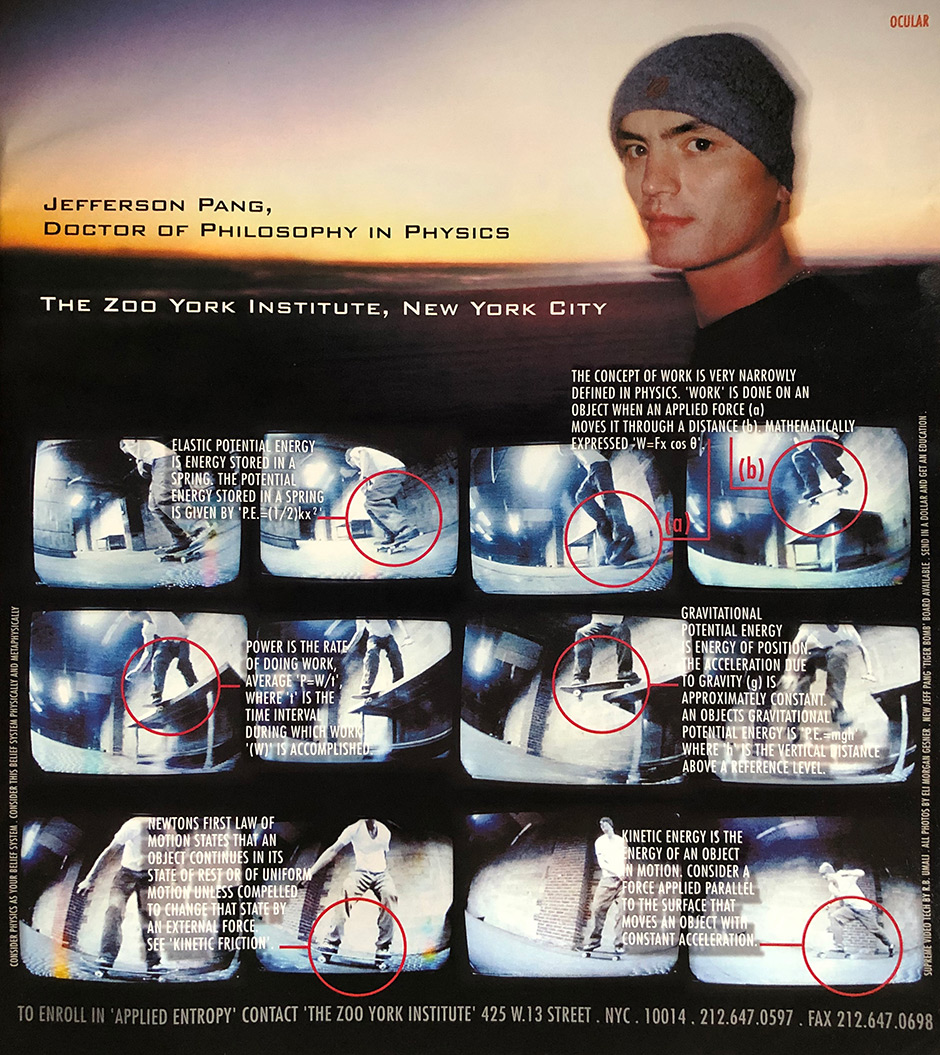

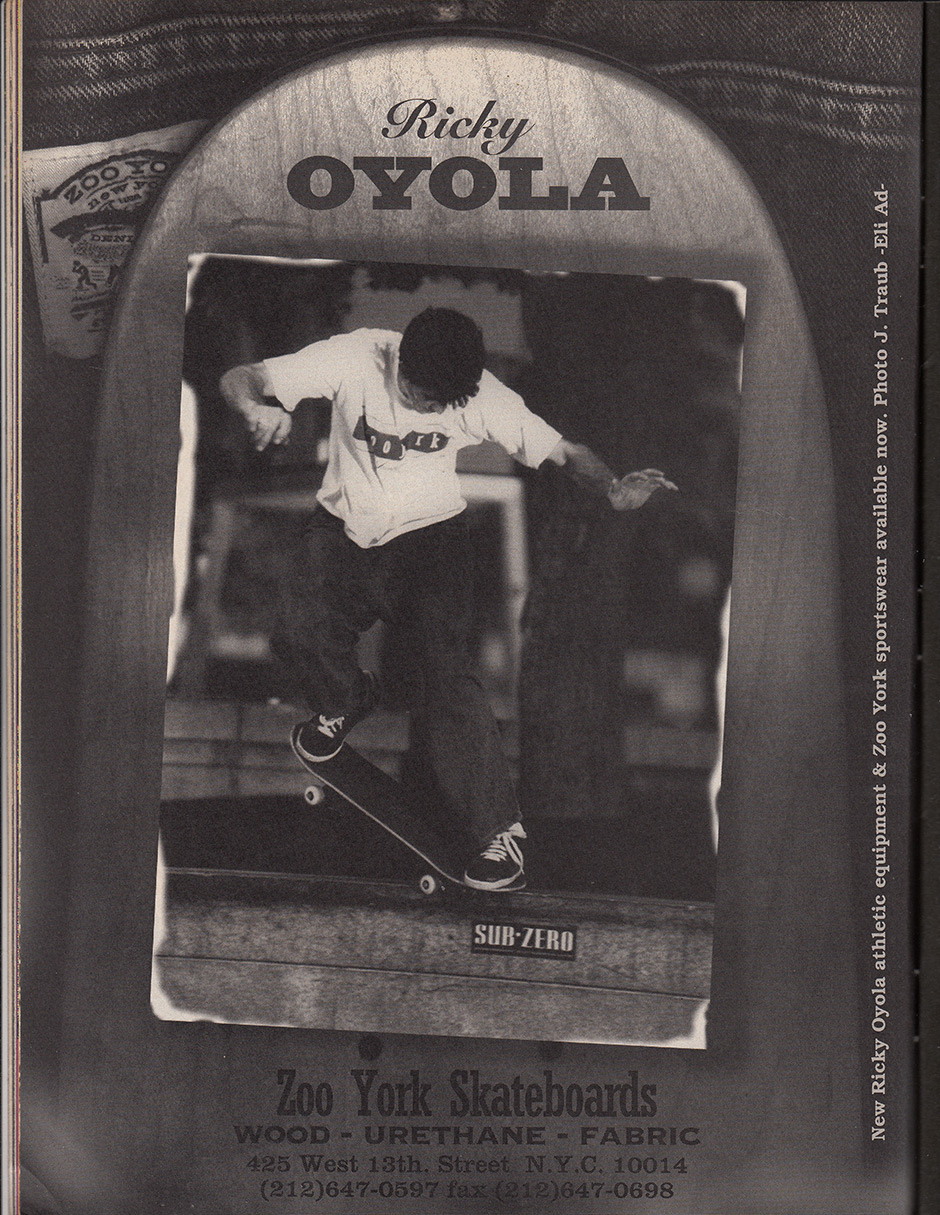

Did people come in from new Jersey and from other parts of the city to skate? Yeah, for sure. But we were the crew. Like an informal skateboard gang who all knew each other. I’m sure it was like all over the world. It was a weird thing how if a group of kids came in from Queens or somewhere, they would just sit and watch instead of skating. Later on, by the end of the ‘80s, I was skating more and more with Jeff Pang and Peter Huynh and those kinda guys and they’d always say how they’d come into New York City to watch us skate. Maybe they thought they’d embarrass themselves, or maybe we were just being too cocky and loud, I don’t know.

Did the Banks being in the Powell videos draw people in?

Oh for sure. That’s a funny side note… When they were filming Future Primitive down there, we were all skating at Washington Square Park. Ian appears and is all, “Dude! The Bones Brigade was here! We shot a video!” so it was like, “Well why didn’t you call us?!” According to Dante Ross, he randomly ran into the Bones Brigade in Washington Square and was like “I’m taking you to The Banks.” Then he called up Ian and told him to meet them there. Just Ian. On the sneak tip. Hahaha! The Bones Brigade were the most famous thing in skateboarding then. Well, the Bones Brigade and Hosoi. When Hosoi came to town he came by himself and basically just hung out with all of us, with the locals. So that was the first time we got to hang out with a pro skateboarder, to see how he worked and to watch him skate.

Was that when he ollied the wall at the Banks?

Yep. I was there that very day.

He was the first, right?

Yeah. That was the first time anyone ollied the wall. Dream Wheels had closed down, and they opened up this other skateboard shop called SoHo Skates which was literally across the street from my school. Ha! How great is that? Next to SoHo Skates was a defunct gas station, with this open area, and Ian Frahm had built a quarterpipe made out of stolen plywood there. It was about four feet high, super tight and just so small. One piece of plywood.

Eight feet by four.

That’s all it was. But it was a quarterpipe and that was the first transition we got to skate. There was this early crew of local New York City kids that was me, Jim Kerr, Aaron Lennox, Spencer Weisbond, Mario Sorrenti the photographer, Beasley, Bruno, all of us local kids and we would all skate this little quarterpipe. The best transition skater was Aaron Lennox because he could do frontside ollies and inverts on the edge… There was no coping. But we were mostly just yanking airs, and lo and behold, here comes Christian fuckin’ Hosoi with Jef Hartsel ready to skate. The fuckin’ first thing Hosoi does is he starts pushing down the hill, going about 100mph, then hits the quarterpipe and does a six or seven foot backside ollie. Hahaha! I can’t even express to you what that was like. A backside ollie twice the height of the ramp, and it was perfect, first try. He was like a total rockstar and we were following him around everywhere, and we ended up at the Brooklyn Bridge banks.

Now the reason that he knew how to huck off a transition was that he came from skateparks, while we were all just street kids doing this form of proto-street skating. Nobody was doing kickflips—I mean maybe Rodney Mullen was doing them, but nobody normal—and we were just figuring out ollies. The main component of every trick was still a boneless, you know? Even Hosoi was doing all sorts of bonelesses, frontside and backside, with the nunchuck-spinning stuff, and wall-climbing stuff. I’d figured out this trick where I’d do a boneless to axle stall on the wall, and then I’d yank it out. Pop the tail and pull it up, and go back into the bank. I was a stupid kid and we were always trying to think up names for tricks because everything needed a name, so that was the Spiderman. Anyway I did one, and rolled away, and heard somebody go, “What the fuck?!”, and it was Hosoi. He was stoked on it! He skated over to me and wanted to know how I did it. I was geeked.

So, at this time, we were starting to do little ollies, but of course the wall is in the way. You can see in the Future Primitive video that Ian Frahm invented the kind of ‘ollie to board rest’ on the wall, where you just yank it back in. So Hosoi was doing that. But then he got off his board and he’s just looking at the bricks, trying to find the last brick that was pointing up before it started bending back away. Then he’s like, “This is the brick!” and he put a Hosoi sticker on that brick. We asked him what he was doing and he said he was going to ollie the wall… On the big side! The sticker was the exact place he needed to ollie. We watched him try it over and over and when he finally did it he cleared the wall by about two feet or something, it was amazing. This guy showed up to our spot and just shit on us. Haha!

Christian Hosoi ollies the wall again on a return visit in 1989. Photo:Kevin Thatcher

I think it was one of those key moments in skateboarding, although we didn’t realise it at the time. A vert skater from California coming into the realest of street skate worlds. We were in our little ghetto trying bonelesses and he brought his vert skating ability, his hucking ability, into street skating and it was the acknowledgement that yes, you can launch like this. That was right at the beginning of the jump ramp era. That was my favourite time in skateboarding.

Was Jeremy Henderson around then? How did Shut come about?

One of the problems about not living in California in the ‘80s, was that when you got Thrasher in April it’d have stuff in it from February, so we’d always be behind whatever anyone else was doing, and that was when things were changing so fast. You’d see a picture of Jesse Martinez doing a judo air off a jump ramp and just be like, “What the fuck? What is that?!” You’d see weird jump ramp variations in street comp articles, up to picnic tables or something, but the idea of just going right over it suddenly popped off. We were in Washington Square Park and Ian Frahm decided we needed a jump ramp, so went off and stole some plywood. We would flip a trashcan on its side, stick a brick under it to stop it rolling away, put the wood against it and we would try jump ramp things off it. Early grabbing, not landing anything, falling around, just a complete disaster. And then this guy showed up, skateboarding, whom I had never seen before and he didn’t look like a kid or a teenager, he looked like a grown ass man. He was physically well-formed, he had a beard, he had a girlfriend who was a woman, you know? So he started skating with us and he was doing ollies. Little scooped ollies without grabbing, and trying backside 180 ollies. And that was Jeremy Henderson.

We couldn’t figure this guy out, I mean he was old, he’d obviously been skating for a long time, but we’ve never seen him before and how is he doing this stuff? He just appeared and was this kind of legendary guy so we started hanging out with him. At the time, me and Alyasha were skating all the time but still trying to write graffiti, little pieces here and there or writing on our skateboards, or drawing on t-shirts for our friends. One day at school, I was drawing in my notebook and I drew a guy doing an invert on the ground, a streetplant. It kinda looked like Ian so I did it in Ian’s full signature outfit, put the planet Earth in and put ‘THOR’ because that was Ian’s tag. I went across the road to SoHo skates and Ian was there skating outside, so I gave him the picture I’d drawn and he just lost it, he thought it was really fucking cool.

One day they took me out for a bagel and told me there were going to start a New York City skateboard company and that it was gonna be called Shut

I’d drawn it in pencil and drew over it in sharp black pen ink, so it had really thick lines and looked like a professional piece of artwork, but it was literally on lined school paper. Then we went skating and I never thought of it again. Two months later, I go into SoHo Skates and Ann, the manager showed me what they’d done. They’d taken that drawing and made t-shirts out of it, the first t-shirts that SoHo Skates made. She gave me two and said that I was now their official artist, which I thought was cool but I didn’t really think anything of it because I was 14 years old or something. People thought Ian drew it, but the people who knew knew what was up, Bruno and Rodney, knew that I drew it, and so one day they took me out for a bagel and told me they were going to start a New York City skateboard company and that it was gonna be called Shut. It was hard to believe because even at this point, skateboarding seemed to just be about California. Zorlac was from Texas but if any other skateboard companies were from outside California, they weren’t announcing it.

At that age you wouldn’t be thinking about how something could affect the rest of your life anyway.

Of course not. Your friends ask you to draw a picture so you draw something for them. But even then I was thinking that it was never going to work, and I was quizzing them about how they were going to get boards made. “Oh, we’ve got a guy, it’s cool” kinda thing. It just seemed like a bunch of people starting a punk rock band or something, it was a complete mess. But still, I went and drew them a logo, the original Shut crest with the two boards crossed, and the city and the barbed wire.

Nowadays everybody skateboards in New York City sooner or later, and there are all these companies around, and riders get stolen and it’s a huge competition, but back when Shut started—and even when Zoo York started—no-one was skateboarding here. So you’d be hanging out with these people all the time, and of course they’re gonna skate for your company. What else are they gonna do? You’re the only game in town, you know? That was part of the genius of what Rodney and Bruno did with the original Shut skateboards team, which was all these kids who could never get a plane ticket to go to California but kill it, they were all in our backyard. Instead of them going out to California, let’s just do it here. So they got their warehouse, and then there’s the famous story of going up on Alyasha’s roof with the jigsaw and cutting out the Shut shark shape.

You went from artist in residence to team rider.

Well that was funny. You see, I was really obsessed with Natas when I was a kid. He was my favourite skater and I loved wallrides. There was a guy at the time, Tony Converse, who was a local Santa Monica jump ramp guy, and in the ’80s he rode for Santa Monica Airlines while he worked in the film industry. A movie he was working on was filming in New York, right when the jump ramp thing was popping off, and I think he ended up living close to Alyasha. Meeting a guy from California was big-deal stuff back then; this guy from California, who skates and is sponsored by Santa Monica Airlines, Natas’s company. So this guy built a proper jump ramp, all out of wood, not some wood and a garbage can thing. He knew how to make it so it had a little kick, and he sprayed ‘V13’ on it, for the Venice street gang, which was so fucking cool to us, and when he would go to work I would look after the ramp.

He had the full Santa Monica Airlines kit, the custom sweater with the airplanes down the arm and all this cool stuff you couldn’t buy. On top of that, he’s ollieing off the jump ramp rather than yanking, and just killing wallrides. So we’re all hanging out, and he’s kinda coaching me, him and Jeremy Henderson, who had broken his ankle. They taught me what I was doing wrong, which was a lot of stuff, because I would just try to go high, by grabbing stinkbug, between my legs, and looking really terrible. So over a few weeks, they explained how to grab, that you should grab around your leg and not through, and how when you’re spinning you need to look in the direction you’re turning. All the stuff that’s important for getting good at jump ramps. I ended up getting good, and had a good rapport with Tony, so he offered to send me a box of boards. A box of boards from Santa Monica Airlines? Fuck yeah! That was a personal highlight of my life, because it was before Shut started and it was who I wanted to skate for.

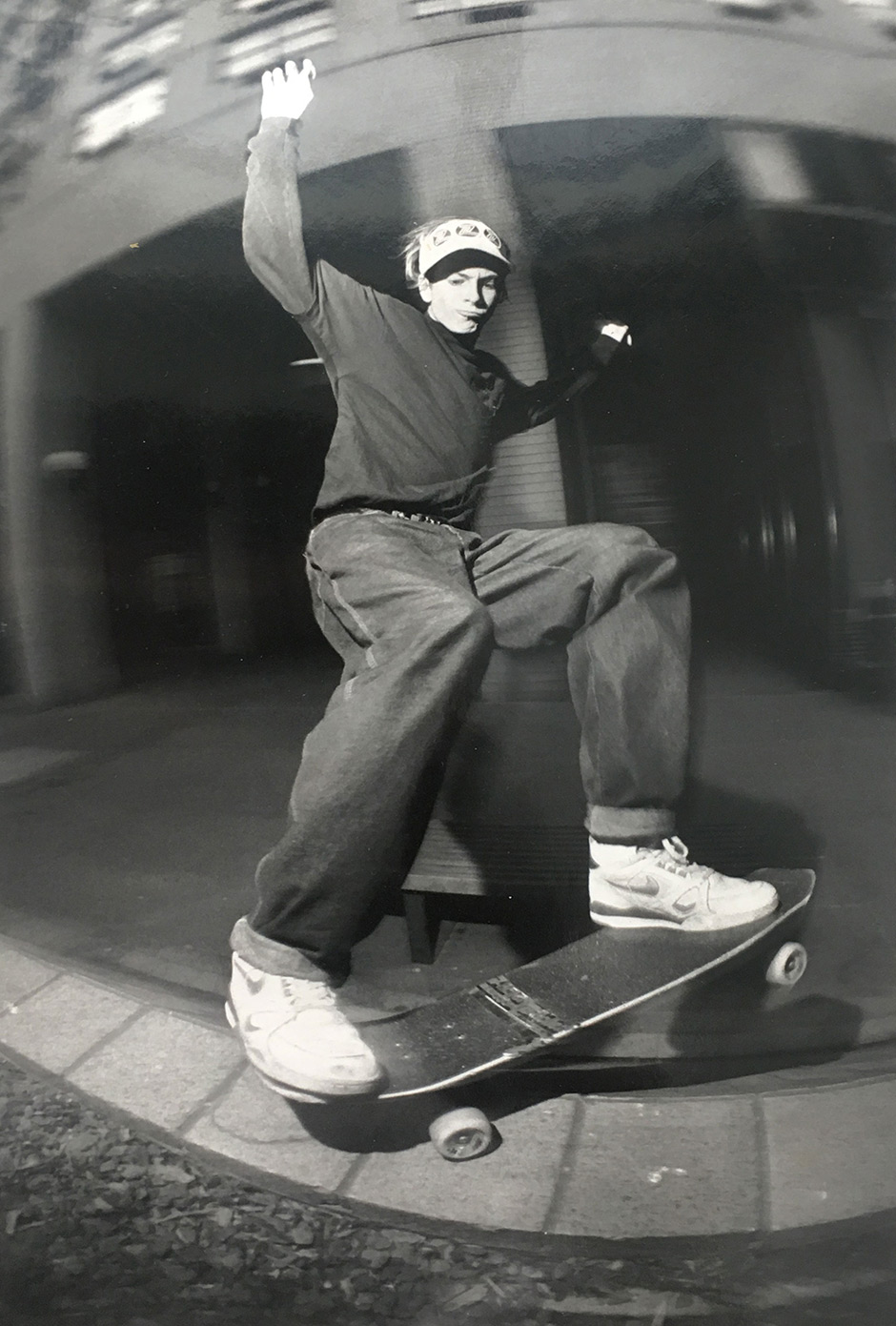

Eli frontside ollies to truck bash at the ASCAP Banks in 1989. Photo: Bill Thomas

Did they send any Natas boards?

Yeah, but the only Natas boards I got were yellow. There was this whole lineage with the Natas boards where they could only afford to make one screen at a time, so the further back you go, the more basic it is. The first Natas board, by Kevin Ancell, was just the triangle, then they added the palm leaves, and slowly all the other elements. But at the time, I didn’t realise how amazing it was to be getting these boards from Skip Engblom through Tony.

At that time, all I knew about skating was what I’d read in Thrasher from 1981 onwards, so I don’t know about Tony Alva or the Z-Boys or Skip Engblom’s lineage or any of that. And here I am in New York City, getting Skip Engblom hand-cut, hand-painted experimental skateboards. He was experimenting with all sorts of new ideas. One of the big problems was how to keep your foot on the board when you ollie, and one of the boards he sent me was this kind of fishtail, with a blunt, flat Natas nose, and he’d used a grinder to carve out wheel wells so the board could turn more. But then he started cutting into the top of the board too, like little shark gills into the front of the board over the front truck, like three or four little wheel wells in a line, and the idea was that when you ollied the edge of your shoe would get caught in these little wheel wells.

Here I am in New York City, getting Skip Engblom hand-cut, hand-painted experimental skateboards

He’d do the graphics too, this custom pinstriping with tape, and all this cool shit. It was interesting because in the graffiti world that I came from, using a stencil was really frowned upon. People were vehemently opposed to masking, or any kind of tape. You had to have the chops to do everything you did by hand, freestyle, and make everything look as sharp as possible by only using your hand. So these spray painted skateboards that had come more from California car culture had pinstripes and waves and fades and ripped up pieces of masking tape, and then he’d put the Santa Monica Airlines airplane stickers on them. These things were works of art!

If I knew then what I know know I’d have kept them so they could be in the Smithsonian, but I would skate them. One time he sent me a bigger Natas board that they were trying to do, with no graphics and the bottom spray painted, but the top had stickers on it, covered by a layer of resin into which he had sprinkled chunks of broken glass, which I think in hindsight came from a shattered car window. So I had this really heavy big board covered in chunks of glass, but it would keep your foot from sliding off when you tried to ollie!

You’re not getting into a nightclub with that.

Yeah exactly. But it was amazing for me to be connected to that company and get those boards from those guys, and when Shut started I was still getting boards from Santa Monica Airlines. With Shut, I mean talk about making it up as you go along! So there was the famous Shut shark logo, and the assault vehicle one that I drew, and various other different things, but before even that we were spray painting on boards and using silk screens and stencils. We’d make a bunch of boards and give them out to Chris Pastras or Coco Santiago or Felix Arguelles or Sean Sheffey or Jeff Pang or whoever. So that was how Shut began, but still the major problem that we were dealing with, was the front foot coming off the board.

You can see on the original Shut boards that we tried making the nose longer; all those first boards had big concave and big scooped-out noses. When Shut started it felt like the end of 1980s skateboarding, so the business model that Rodney and Bruno used, which ultimately led to their downfall, was to take an inventory position. So they were renting a huge warehouse and instead of getting sixty of a board for ten bucks each from the factory, they would get 500 boards for five bucks each, to get the price down and make a bigger profit. Up until that point companies were making 1,000 of something like a Rob Roskopp board, then another 1,000 of the same exact board because the shops wanted to reorder it.

Another 1,000 of the same graphic but in a slightly different colour.

Exactly. You know Mike Vallely skateboards specifically because of Rodney Smith?

Go on.

Rodney Smith is from New Jersey, and his little brother is Chris Pastras who started Stereo skateboards.

Wait, what?

Not biologically, but Chris’s mom was a single mom and she was too busy, so she let Chris stay with Rodney’s family because Rodney had a big house with skateboard ramps. So Chris basically lived and grew up with Rodney’s family. One day Rodney was skating around and this young skinhead punk dude starts glaring at Rodney, vibing him, but Rodney takes the time to talk to this kid, and invites him round to his house to give him a skateboard. And that was Mike Vallely. So Mike Vallely and Chris Pastras and Rodney basically grew up together in Edison, New Jersey. Mike was supposed to skate for Shut but he was so good that he immediately got picked up by Powell. Who could say no to that?

So Mike goes off to skate for Powell and he becomes this huge star, just as Shut starts, and skateboarding starts fizzling out late ‘80s, and although the cool thing is street skating, nobody has yet resolved how to keep the front foot on doing an ollie. So at this point, Mike Vallely, who only skates because of Rodney Smith, goes to World Industries and they do a board with two tails. The famous double tail Barnyard board. And that just changes everything. Now you can do ollies, nollies, everything. And when that happened, back in New York City, Rodney Smith and Bruno Musso are sitting in a warehouse with 2,000 Shut scoop-noses that no-one’s gonna buy now, so that whole company completely fell apart. It was so bad. Their whole skateboard team all got stolen by Californian companies and they all moved out there. So that was around 1990, when Shut just fell apart.

It was in the late ‘80s that you managed to get beta copies of the first versions of Photoshop and Illustrator. Tell me about that.

Here’s what happened. I was never a good student at school, I was always kind of a screw up, but I’ve always had a good relationship with computers. I’ve never told anybody about this, but when I was a kid, my neighbour’s dad was an astrophysicist for Columbia University, and in his house, around 1975, he had a computer. In his house! It was about the size of a refrigerator, and it was just brackets, just the metal box and circuit boards, motherboards, all wired together taking up all these shelves. At the very top, six feet off the ground, is this 10” x 10” green and black screen and a keyboard. One day he asked if I wanted to play a game, and at the time there was maybe Pong, but games were not in arcades yet. This was the first video game I played and it was a Star Trek game. You were the Starship Enterprise and you were fighting a Klingon, so the screen was completely black expect for the Enterprise, which kinda looked maybe a little bit how the Enterprise looked from above, like two lines and a circle, and then the Klingon ship was a little triangle.

So he’d sit there and tell me, “You’re going north-west at four parsecs, and they’re going south-east at five parsecs, so where do you want to go?” and I’d point on the screen where I wanted to go and he would type it in. Nothing was moving, it was just a still screen with a circle and a triangle, so he’d type in the co-ordinates and press return and the computer would calculate the movement and draw the screen again. It was like turning a page in a book. So I already thought that kind of thing was futuristic and cool when video games started happening, Pac-Man and all that.

Around that time I went to York Prep., which is a fancy preparatory school on the Upper East Side, which was a complete disaster because I was a complete failure as a student. I didn’t do homework, I didn’t do class work, I was just getting into writing graffiti, my dad had just died and I was a complete mess, but they had a computer department that had this early computer called a PET.

We did very basic code writing, very basic BASIC, but I was into it and I kinda understood it. This was the future. Period. I had a good rapport with the computer teacher, and they had this school-wide computing test that I got 100% on, and all the bonus questions, so I thought I would be rewarded for that but because I was such a bad student they accused me of cheating. Haha! So I got mad at them, like, “Don’t you think that if I was going to cheat on a test I might cheat on one that would affect my grade rather than a computer literacy test?! And if I did cheat, do you think I would intentionally get every fucking question right?”, so they kicked me out of the school. Then I got kicked out of every other school in New York and I got sent away to boarding school for my last three years of High School. That was 1985 or ’86, when the Apple Macintosh came out, and my school had an entire Macintosh computer lab with an amazing instructor from Apple. Suddenly, I could finally draw and animate stuff. I did a little video of a kid skateboarding and ollieing over a trashcan and doing a backside 360 off a jump ramp. Haha!

Where was that?

It’s called Forman, and it’s in Litchfield, Connecticut.

So far away from everything you’d always been around.

I think, ultimately, that helped me. I needed that because I was just running around crazy because I had this heavy reputation in New York City at such a young age. I could get away with murder.

But wasn’t it heartbreaking to have that taken away?

Of course. I couldn’t go anywhere else, no school in the city would take me. Thank god for my family, because even though I was a complete fuck-up and a maniac, they still supported me and would be hard on me, telling me I needed to get my act together and I can’t make a career out of skateboarding. Part of that was also because my dad was an artist—he was a Fulbright scholar and one of the guys who helped create the School of Visual Arts—and my uncle was a Broadway playwright, so I just grew up around artists. Every one of our friends were artists, and I was a really good artist because I grew up with professional artists teaching me how to do artwork. Haha! It wasn’t like, “Here’s a colouring book”, it was more, “Here’s some graph paper, here’s how you use a Rapidograph, here’s how you sharpen a pencil with an X-Acto knife”.

I was always the best artist in the school, and with everybody telling me how good an artist I was, and telling me that I was going to be an artist, I didn’t know why I was even in school. What do I need to know Math and History for? So that advantage backfired on me, and it fucked everything up for me. That was how I ended up in the boarding school. So I’m this New York City kid out in the country, walking around this school trying to find skate spots, and lo and behold, behind the dining hall, there’s a six foot quarterpipe, already built. And I wasn’t the only kid there that decided to go there because they saw the ramp. There were two other guys that skated, so even though I’d been taken away from New York City, me and these guys had a skateboard ramp to ourselves.

I’m this New York City kid out in the country, walking around this school trying to find skate spots, and lo and behold, behind the dining hall, there’s a six foot quarterpipe, already built

Having that thing there must have been pivotal, in terms of the rest of your life. You could have had everything wrung out of you there. As the intention might have been.

I can’t say enough good things about that school. Forman is designed to help kids with learning problems, or fuck-ups and screw-ups, or kids who have dyslexia or ADHD so it was a really good place for me to go and they were super supportive of all things creative that I was into. They had a really amazing arts program, they taught me how to make films and gave me access to movie cameras, and they had their computer lab. When the Macintosh came out it was still so early that all the programs were made by Apple. So MacPaint, and MacWrite, and MacAnimation… Computers seemed cool but it was still 16-bit, crappy black and white stuff, which might be cool for a part of a graphic that I might put into a Xerox machine, but there I didn’t see a future in it.

When I graduated, in 1988, the last month I was there, Apple came to the school to do a presentation in the computer lab, and they had the Apple II, which was the first full-colour, photo-realistic computer they were going to offer. They probably had an early version of Photoshop but I didn’t know what it was, I just saw this 3D graphic—a still image of a reflective silver sphere on a checkerboard floor. I can make that on this in my room? So when I graduated, my family—because they’re so awesome—asked me what I wanted as a graduation present, and I wanted an Apple II. I got it, but it was so new that there was nothing for it, no programs, so I basically sat there and looked at the preferences, just seeing how it might work, you know? There was a writing program where you could write stuff, but no way of drawing.

My mom was an art director, she moved away from that to become New York City’s pre-eminent headhunter for computer graphics, but at this point she’s still art directing so I ask her to ask her colleagues what I need to do to make this computer work. It turns out one guy she works with is beta-testing Illustrator and Photoshop, and so behind Adobe’s back he made copies of the programs and sold them to me and my mom illegally. Hahaha! We met him in a McDonald’s, he gave us an envelope and my mom gave him $100 or something. Everything’s on floppy disk, so you’re loading installer disk one, installer disk two, installer disk three and so on forever. Then you load up Illustrator and learn how to draw a square, and then colour the square. Then you learn how to draw a circle, and colour the circle. But nothing was in colour in real-time because the computers were still so weak.

So I was using the pen tool to draw graffiti letters, to write something like ‘Fresh’ or whatever, but it would just be points and lines so I’d fill it with a fade but you’d have to do it all in your head. Like, the ‘F’ is going to be red, the ‘R’ is going to be orange, the ‘E’ is going to be yellow, the ’S’ is going to be baby blue and the ‘H’ is going to be dark blue and then you’d press CMD+R to render and just sit there while it would draw what you wanted. It took forever. Anyway at this time I’d got into film school, at the School of Visual Arts, and I was just skating, working out Photoshop and Illustrator, and going out to nightclubs. I wasn’t into partying or getting wasted, drink or drugs, but I think after being at boarding school I just wanted to be around people.

To see what’s going on.

Yeah, so I was going out to nightclubs, and listening to a lot of hip-hop. Hip-hop was moving away from the ‘hippity-hoppity’ thing and evolving into the newer, early-‘90s stuff. That was pretty much my life and everybody in New York had pretty much stopped skateboarding. All the guys that were good enough to do it for a living, the Jeff Pangs of the world, the Chris Pastrases, the Sean Sheffeys, they all left the city and went to California, so everyone who stayed in New York and went on to do other stuff, like Mario Sorrenti who went on to become a very famous fashion photographer or Dante Ross who went on to make music. So everybody I had skateboarded with had vanished and I was skateboarding by myself.

What had happened at Shut by this point?

Well Shut was trying to keep it going, and they had Jeremy Henderson, but the whole original Shut mega-team of Coco and Barker Barrett and Sheffey was over. All those guys left, and the only people around weren’t making any noise. Manufacturing had become a problem but they were still trying to keep it going. And they had a warehouse full of old decks they couldn’t sell. I was still skateboarding for the fun of it but that core group who’d grown up skating in the ‘80s had all moved on to surfing.

Andy Kessler and Bruno too?

This is no diss to Andy Kessler, and it’s public knowledge, but at this point he was in a really dark place, he had a drug problem. I knew Andy and I grew up with Andy but at this point he was just keeping to himself. I think he was the manager of a pool hall but I didn’t know he had a drug problem so I’d be asking him to come skate but he’d just be doing his pool thing. So anyway around 1990, or ’91, I’m going to college and I’m living with my mom and sister on the Upper West Side in this three bedroom apartment and my mom decides that she wants to move. She’d been wanting to move for about a year, looking for a place downtown that she loved, and she found it, but the problem was that it only had two bedrooms, so she came to me when I was 19 and said, “Eli, I’m moving out and I’m taking your sister. You’re going to have to live here by yourself”. Woah.

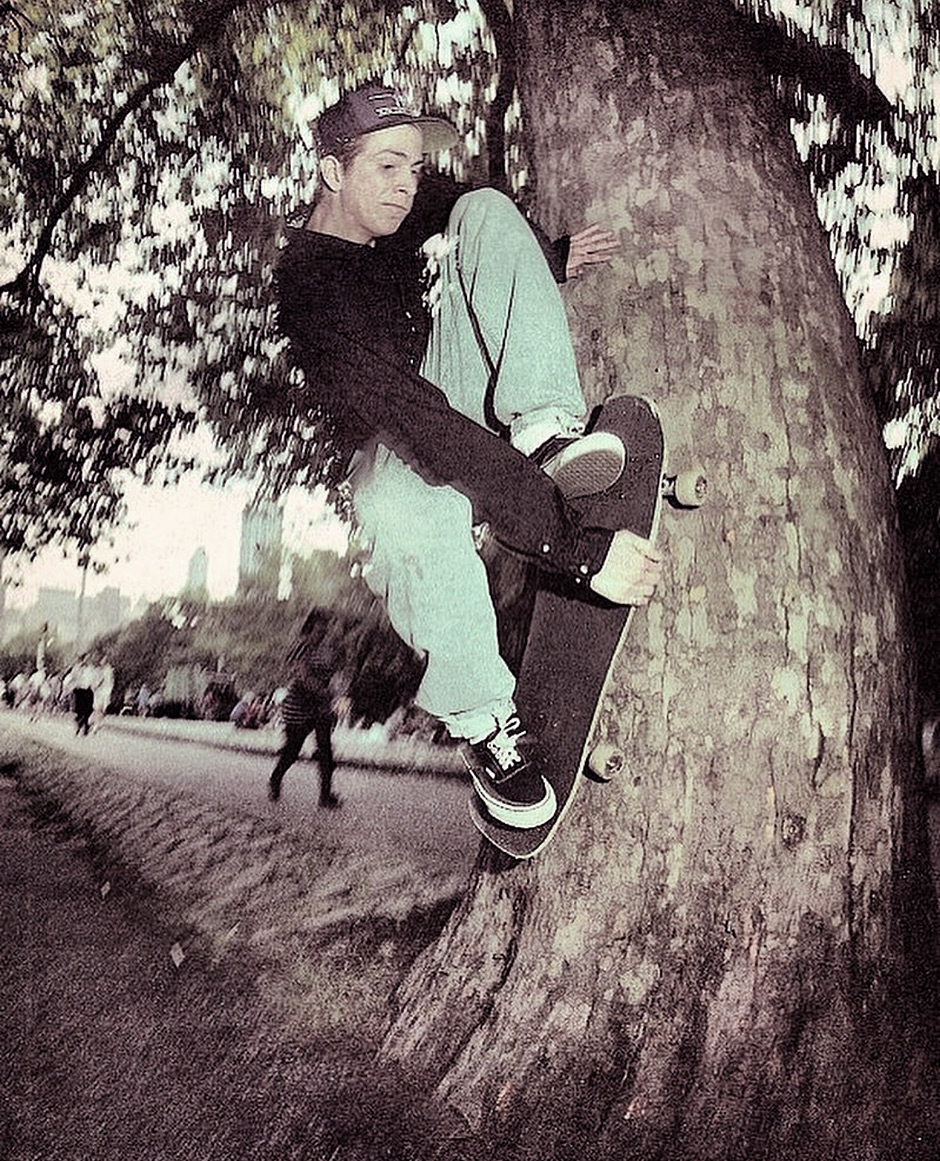

Eli blasts up a tree in central park

I was just like, “Fuck yeah!” That was a big win. It meant I could let people crash there, all the skaters that would come through would have a room. It was while this was all going on that the Shut thing collapsed. They lost all their money, Bruno took off and they just left all their skateboards in the warehouse.

Big changes.

All my friends had basically left New York City, I was going to film school, I had my mom’s apartment and I had computer skills in Illustrator. I’d been working as a hired gun for big design firms who needed Adobe Illustrator mercenaries, and from going out to nightclubs I’d been making connections there. A new nightclub called Mars opened and they needed promoters, so a friend of mine, Carter Smith, told me that I could get $100 a night to go around with a knapsack full of flyers and hand them out. I was at the tip of the cutting edge in terms of working with computer graphics and I was learning the craft of design and printing from working as ‘the computer kid’ for all these senior graphic designers.

I was in this little happy place, making all this stuff. One of the other things that comes into play here is that I had sort of skated for Stüssy in the mid-‘80s. My friend Paul Mittleman, who was a local kid, had a family who had a clothing shop that sold new-wave clothing in the ‘80s, the fluorescent and checkerboard stuff, and Paul had built a relationship with Shawn Stüssy when he was still just a surfboard shaper. One of the first places that Stüssy t-shirts were ever sold was at Paul’s family’s clothing store on Broadway.

What was Paul’s shop?

It was called Pandemonium.

It wasn’t ever called Paul’s Boutique, was it?

Haha! No. That’s just coincidental. Now because Paul had connections with the real New York City fashion lines, him and Shawn kinda partnered up. They got a showroom and Paul was kinda second-in-charge there, under Shawn Stüssy, and they would give me shirts, and stickers for my Santa Monica Airlines boards, but it was a weird time because it wasn’t like it is today, where you need to represent for your sponsors and deliver clips and photos. It was more just, “Oh, you hang out with all the cool people, here’s some stuff to wear”.

Did you acknowledge at the time that these were the ‘cool’ people?

One hundred percent. The idea of ‘cool’… This is something I’ve considered writing a book about. The word ‘cool’… The idea of what ‘cool’ is comes from originally comes from American jazz musicians during prohibition in the 1920s.

Yeah.

When they’d ask if someone was cool, it meant, “Is this guy cool? Can we smoke weed around him? Is he a cop? Can we go to a speakeasy and drink, or go to a whorehouse? Is this guy cool?”, but that changed as it continued on. Being cool used to mean that a select group of people would sign off on you. It was almost like chivalry, like how your ‘reputation precedes you’.

Cool used to mean ‘counter culture’. Against what everyone else was doing. What normal people were doing. Now, what it’s turned into, which me and my contemporaries are sort of at fault for, is that ‘cool’ means that you’re doing something on some predetermined checklist, like you’ve got the right pants on and the right pair of shoes and you bought it all from a specific company.

‘You’ve spent the most money on the right stuff, you’re cool’.

Exactly. What it’s turned into is a consumer culture. What’s tragic about it, and I see it all the time, is people dressed head-to-toe in Yeezy or Supreme, and it’s really just an announcement that they have money. You can even see from these guys that they’ve never been in a fight, they’ve never been to a museum, they’ve never read a book, all they care about is collecting. Their skill set is that they are able to pay for cool stuff.

People who have never seen Skypager.

Exactly. I mean cool people do still exist, But they are not people who just purchase ‘cool items’. To me you could be dressed head to toe in the right thrift shop clothes and shit on any Off White anything. If you’re somebody like Jason Dill and you’re selling Fucking Awesome in Supreme, you’re still a cool guy because you know what good music is and good art, but you can tell somebody who has stood in line for twelve hours to get the drip.

Don’t wear the same brand head to toe. That’s the worst.

It’s all been so abused now that it has no meaning anymore. The actual ‘cool kids’ here in New York might have one or two Stüssy or Supreme shirts, but the kids in High School who are gonna be the future are almost exclusively all thrift shopping; they all want clothes that no-one else has. I mean, you know you can get those limited edition sneakers if you’ve got enough money, but if I put the effort in and go thrift shopping and find a 1989 World Series t-shirt with Michael Jordan on it, then you could be the only one in the world with that.

Current companies are making that stuff now, making clothes that look like they’ve come from a thrift store. It looks cool and interesting but it’s got a skateboard company label inside it.

I don’t really know where this is all going, but it’s a fad that’s really blowing up in the States.

Those people can feel more secure buying something for $50 if it’s got a label they know inside it. They’d ignore the same thing for $1 in a thrift store because they wouldn’t know if it was safe to wear or not.

Right. That’s the trick. I have, on the record in various places, been saying that Supreme—and those guys are my friends and I love them all and they’re great designers who do a great job—to a large part of their consumer base, what they are selling is a false sense of security because the kids who are buying it, if they get dissed for what they’re wearing they can always say “These are Supreme and they cost $1,000, so fuck you!” and that is the corniest thing ever.

It’s almost like they’re cowards; they’re scared of taking a risk or being ridiculed. All those companies are selling security blankets for cowards. I think people are aware of it now because a lot of the kids who are Supreme-heads or sneaker-heads or whatever the fuck it is, are just the saddest kind of people. They’re almost the same as what computer nerds were in the ‘70s, that kind of level of dork. The ‘I live in my mom’s basement and collect action figures’ type guy. I feel that there’s a component of that nowadays in people who are ‘hypebeasting’.

People accumulating all these clothes then hardly even wearing them.

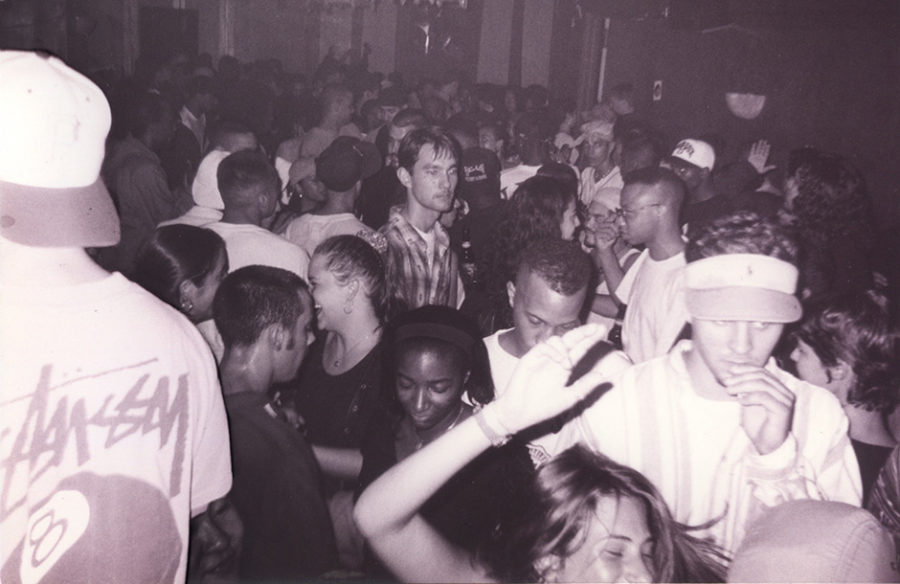

Ha! Exactly. So to go back, I was getting Stüssy clothes and I had a connection with Paul, so when I started doing the nightclub and it started doing really good we got the idea of doing a Stüssy night. That was right when Stüssy was blowing up and everybody loved it, and streetwear was still mysterious and nobody knew how anything was made. It was a new frontier.

That was right when Stüssy was blowing up and everybody loved it, and streetwear was still mysterious and nobody knew how anything was made. It was a new frontier

You were putting your own club night on?

Yeah, and to make a long story short, I was the guy who saw that you could bring hip-hop into nightclubs. I would stay at home and listen to hip-hop, and then I’d go out to nightclubs but it would all be house music. They would never play hip-hop because the hip-hop parties always got shot up and they got shot up because there were so few places to hear it! It would always bring in a criminal element, and people who had beef with each other. So me and my friends Beasley, Yuki and the Duke of Denmark started the hip-hop party at Mars on Friday nights called Trip, and it blew up. It was the first time you could go to an established nightclub and actually hear hip-hop music.

So we do this Stüssy night, and everybody who is anybody in hip-hop in New York City is coming to our party every week and everybody knows that we’re the promoters. My buddy Beasley passed away; he was a black guy who also used to skate for Shut, so I was the white guy and he was the black guy, we were two cool guys in New York City who skateboarded and wrote graffiti and everybody from Washington Square Park, and all the rappers and graffiti writers in New York City, would come to our party.

The Stüssy party wasn’t going to be a promotional thing, it was just that every week we would try to come up with a different theme just to keep it interesting, so I pitched the idea to Paul and right away Shawn went a drew a pass that said ‘The International Stüssy Tribe party’ in his handwriting. It was great, so we sent it to the printer and I was really proud of it because I was such a fan of Shawn’s, and here was my party being advertised in his handwriting.

What was the tie-in there, beyond getting the people from the shop down?

People would come to the parties anyway. One of the things I hated about going out to parties was that, because I went to every nightclub every night, I knew everything at the clubs and I always hated when somebody would be like, “Oh, come to my party, we’re doing this different thing” and I’d go along and it would be the same as it always was. I felt conned. So we always tried to try something that was unique, and that really started with the holidays. We’d do a Halloween party, a Christmas party, those kinds of things. So there was always at least an attempt to make it something interesting. We did a Shut night once, and invited all the skaters. Stuff like that. We did a reggae Christmas party!

There’s some great Christmas reggae! This is an important part of New York City’s nightclub lineage though, how things were curated and created by the actual people.

Exactly. One of my heroes, although I didn’t realise it at the time, was Eric Goode. Eric Goode and a guy called Rudolph. Before I could start going out to clubs, when I was a little kid, the cool club in the city was called Danceteria, and Danceteria was famous for its multi-levels with different kinds of music. All the graffiti writers would go there, Dondi and Futura, and that’s where Madonna’s career started. So Rudolph, this blonde German guy, was the head promoter for Mars, so when I first got there I knew there was good lineage there because I loved everything that came out of Danceteria. At the same time there was the rave thing going on, at the other end of the club world. The crazy drug-using, dressed-up-like-a-cartoon-character shit. But I knew all those guys too, and I’d see them and think how it must take them five hours to get ready to go out. Michael Tron and Michael Alig. He’s the club kid who killed his drug dealer.

All these crazy, creative people were in this night life scene. But a lot of the time, there was not a lot of effort put in to the parties. So when when we had this Stüssy party, we really made a push. People wondered how we got the coolest clothing company to represent and stand behind our party and I was very proud of that. The Friday night comes and I show up early to set up as usual, and the guys at the club told me a load of boxes had showed up for me… Without telling me, Stüssy had made 500 t-shirts for the party. I couldn’t believe it, I was so stoked that they went and spent the money on that. That they thought that the club I was doing had enough impact that it was worth Stüssy making all these tee shirts to give away. I was making a tangible effect. I could just give these things away to everybody. Throw them into the crowd. That was even before cross-branding stuff. So while this is going on, Russell Simmons… You know who Russell Simmons is, right?

He’s my next question.

Haha! Right. So at this point in his life Russell Simmons is making a lot of money with Def Jam, he’s like the big man on campus, and he’s spending time at a fancy, high-end clothing boutique in SoHo called Bagutta, who had the exclusive contract for Dolce & Gabbana in New York City. For whatever reason, Russell had become infatuated with fashion models, and he’s taking fashion models to Bagutta so that they’ll ‘like’ him. Now, around the corner from Bagutta was the Union Stüssy store. It was called Union but they had the exclusive for Stüssy, and it was owned by James Jebbia.

So James Jebbia had this little boutique around the corner from Bagutta, and Mark Bagutta, the owner of it, notices that all the cool kids are hanging out there. He sees that they’re all listening to hip-hop music, wearing baggy pants and buying Stüssy, so he gets Russell and brings him round the corner to the Union store and tells him that because he’s the king of hip-hop, he needs to start a clothing line like Stüssy. He agrees, and ends up coming to my party where I’m throwing all this Stüssy stuff out, giving it away, and figures that I know how to make clothes. Which I do not.

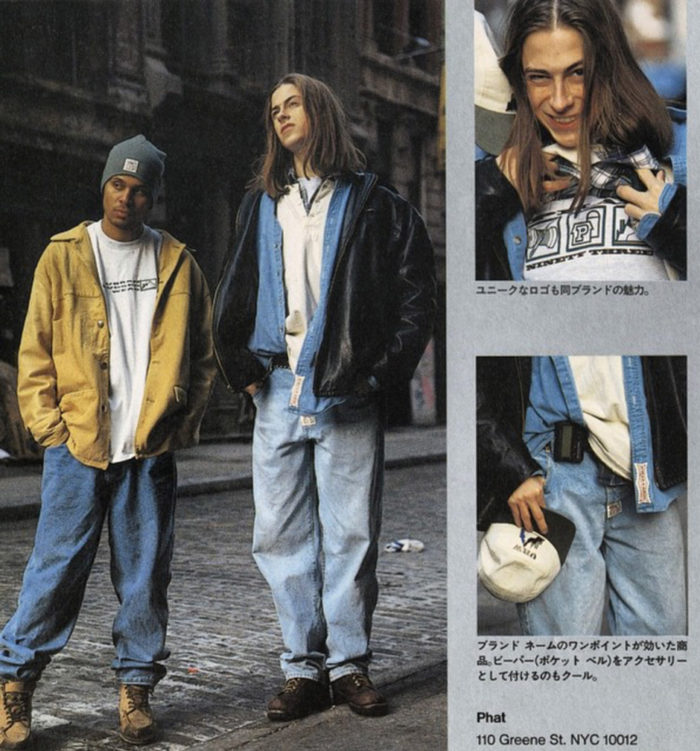

We also had a friend in common, Dominic Treniere—who also passed away—who wasn’t really a skater but was into high fashion and hip-hop. Dominic basically made the careers of Maxwell and D’Angleo. So Russell is asking Dominic who I am, who my crew is, and he says that Paul Mittleman does the Stüssy thing, Eli and Alyasha do graphics and they all skateboard together. So we get this phone call from Dominic telling us that Russell Simmons wants to hire the three of us to start a clothing line, similar to Stüssy but more hip-hop. Like the Def Jam version of Stüssy.

So we get this phone call from Dominic telling us that Russell Simmons wants to hire the three of us to start a clothing line, similar to Stüssy but more hip-hop. Like the Def Jam version of Stüssy.

The guy that put out all those Public Enemy and Run DMC records hiring a skinny white kid with glasses from the Upper West to do his clothing line was pretty interesting.

Oh for sure. I think we all know that hip-hop is a black thing, but Russell’s partner was Rick Rubin, who was a white heavy metal guy, and they ran Def Jam out of their NYU dorm, and the Beastie Boys were down with them. There’s always been the thought that if you can get white kids involved in it, you’re going to make more money. That’s the whole reason why Walk This Way even happened for Run DMC and Aerosmith. To cross over, unity. To make the suggestion that we’re all in this together.

I guess that’s also why 3rd Bass happened.

Oh for sure! So ultimately when it came time to start this, Paul Mittleman did not want to start it with us, he wanted to go do his own thing, so the whole Phat Farm thing was me and Alyasha, and Russell loved it. Alyasha’s a light-skinned black guy and I’m a white dude, and he loved that dynamic of, “We’re from the streets and were making clothes”, but this was also unproven territory! People were wearing Tommy Hilfiger and Polo and Nautica and North Face, and no-one’s wearing any kind of culturally-related brand or anything like that, so this was a big risk for him and he put a lot of faith in me and Alyasha. It’s a whole crazy story about how that all came to pass but I was a lucky, lucky kid.

Polo and Tommy were the shit though, and skateboard companies weren’t making good clothes. It was hard to get but it was worth it.

When I was a kid growing up you had to get the Dickies pants from the construction supplies place, you had to get the Champion sweater from the sporting goods store and there was only one place in New York City that sold Vans. If you wanted North Face you had to go to some outdoorsman shop. We had no Supreme or Diamond Supply Co. or Billionaire Boys Club. I think it’s Pratt, the art school, who are offering an entire curriculum on streetwear now… When I talk to people that tell me they have a clothing brand nowadays I find it hard to wrap my head around that because I suppose there’s traditional fashion design where you have the idea of a silhouette and then you go find the fabric and then you earnestly go and design clothes, but where I’m from it’s more about cobbling together a look because there was nothing available.

That was what made you cool, because you knew the ‘cool guy look’ and you somehow knew people who could hit you with where to get everything. Once you had that outfit on, with stuff from all those different places, and you walked into Washington Square Park or walked into the club, people would know you knew what was up, because you knew where to go to get those things. Nowadays you don’t need to know that. You can be the biggest idiot in the world and just go online and tap ‘buy’ and as long as you’ve got a pay cheque you can fake it like you know what’s up, but you don’t know what’s up. You’re just buying stuff.

Wearing the shit that was hard to get, the stuff you had to travel for and ask around for, was so much more rewarding than going into a skate shop and buying whatever’s on the shelf.

That’s the big difference between the culture then and what’s happening now. It’s like with music, you’d be listening to the radio or watching MTV and then be like, “Devo? Who are these guys?! How do I get their music?” and the only way you’d get those answers was to get on a train and drag your ass to the record store, then get vibed out by all the guys who work there but eventually spend enough time there that one of them talks to you and explains who Devo are and where they’re from and what records you should buy. It was a trial by fire but it was an education, and then you were master of that knowledge and could go back to your friends and explain to them what Devo are all about.

I think there’s justifiable gatekeeping in certain parts of certain cultures. Having all the right kit doesn’t mean you win.

A lot of the young guys who skate for us now are still in High School, and I asked them what they were even learning. Every paper they could possibly write has already been written and you can just download it now, and if that’s the case, why do you need to know anything? If you want to know who Devo is you just need to Google it. And those guys, universally, were all, “Man, it’s crazy how much stuff you guys remember!” They’re amazed that their parents and me can remember songs and scenes from movies. It’s like people don’t want to have a memory anymore. What’s the point? All the information is readily available.

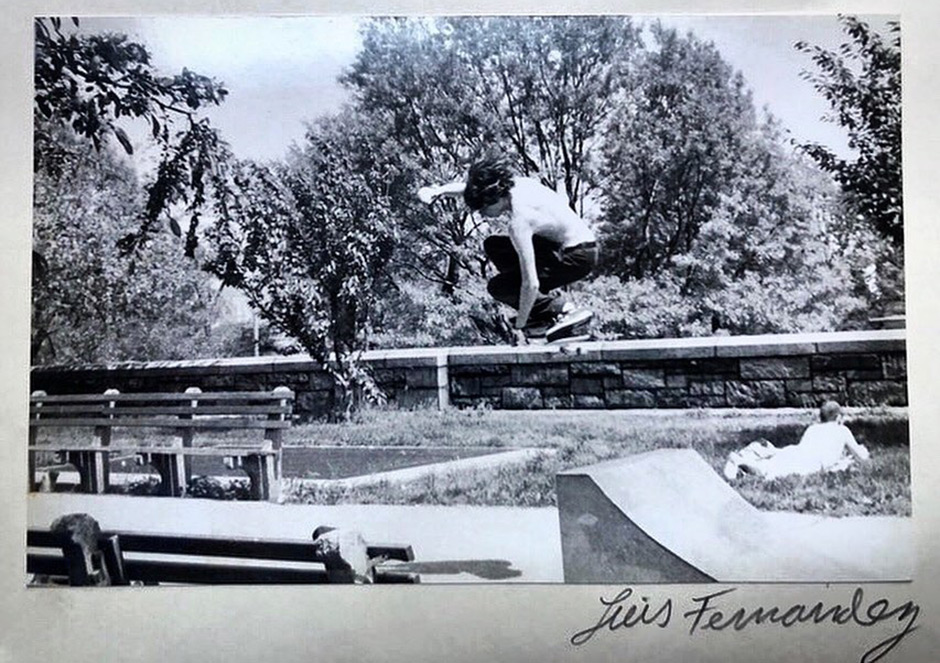

Eli flies out of a jump ramp in Riverside Park. Photo: Luis Fernandez

That’s something I think about a lot. I realise now that when I was a little kid, watching the first New York guys skate on the quarterpipe in Riverside Park? Those guys still had to go through the same shit that I had to go through. They still had to learn to how to put a skateboard together, and if they’re listening to, say, It’s Just Begun, how do you get that record? Who is that?

The Jimmy Castor Bunch.

Jimmy Castor! So how do you learn about that song, where do you go to get it, all that stuff. I’m 50 years old and for 40 years of my life, I felt like I had a very firm grasp of everything culturally. I knew where the music was coming from, I knew where the clothing was coming from and everybody who was making that stuff was referencing stuff that I understood.

I loved going out to clubs since I was 13 or 14 years old, seeing what people were doing, see what was going on and hearing the different music, but recently when trap-rap took over, when mumble-rap came out, Soundcloud, stuff like Migos and Lil Yachty, I couldn’t get behind it. I don’t like how it sounds and I feel like it doesn’t reference anything. It’s not hip-hop. It’s something else. I wish they, the creators of that style, made up their own name for it… ‘Lazy Phaze’, or something unique to them. Something not ‘rap’. I know it’s now the most listened to music, but it’s not hip-hop.

I think people’s insecurity led to that homogenisation of pop music. Nobody’s going to be the person to say, “Hang on, isn’t this total shit?” to their friends.

When I was listening to punk rock and my grandfather would ask what the fuck this terrible music was, I could explain that it’s meant to sound like that because the music industry had become so commercialised so this was a reaction to that, so when the younger guys I was skating with were listening to mumble rap I asked them why, and they’d tell me it was ‘cool’—there’s that fucking word again—I’d ask them to explain why it was cool but they don’t have anything.

It just seems that because of some magical Soundcloud algorithm, this sound sort of randomly percolated to the top—barrel of crabs—and kids, not wanting to be ostracised by seeming like they weren’t into it, just went along with it. ’Robots tell me this is cool’. And everyone just agreed that this is dope. But maybe I’m just out out touch, I don’t know, I would love for someone intellectual to prove me wrong.

Alright, so Phat Farm.

Right. So that was kind of a mess, we really didn’t know what we were doing, but it worked out in the end. A lot of bad blood got boiled up because, on one hand, Russell had this fame and recognition, but these guys had been my friends all my life. We ended up turning on one another, and it got really dark. On top of that, no-one knew if it was going to work, if people were even going to buy this stuff and be into it, but it 110% totally worked.

People were queuing up at the stores to buy it, but at the end of the day me and Alyasha didn’t have any ownership, it was entirely owned by Russell Simmons and we were his employees. There was no upside to it and I felt a bit cheated, because it was a brand identity that I made with my friend and a lot of the stuff we made, we had to fight for, because Russell wanted to go in another stupid fuckin’ direction that would never have worked.

Alyasha Moore and Eli Gesner. Phat Farm Days

You saved his credibility. I think if he’d blown it with Phat Farm, at that time, he’d have been fucked.

Exactly. That’s part of being an artist. If you’re fortunate to have the money and be able to go do what you want, there’s no guarantee you’re going to make something awesome, and there’s a huge argument for the thought that there needs to be somebody involved who’s only interested in making money to keep you in line because, whether it’s a clothing line a skateboard company or anything else, you could make a pile of shit that nobody wants to look at and only has meaning to you and your friends. If you’re a painter and you’re hanging up paintings that people want to see, then that’s the purest form of art that you can do, but once you start investing money and manufacturing you have to be sure that people will want it.

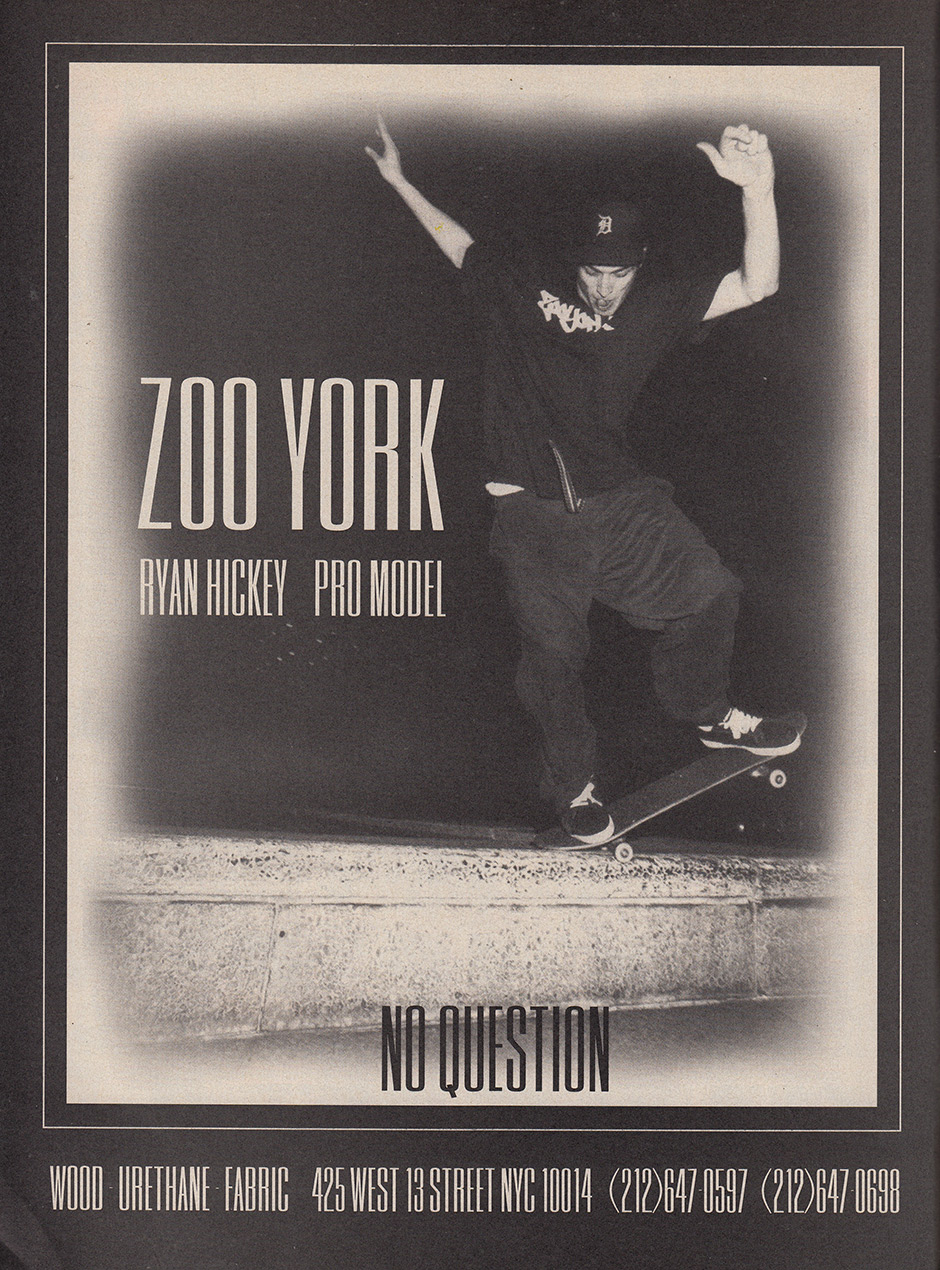

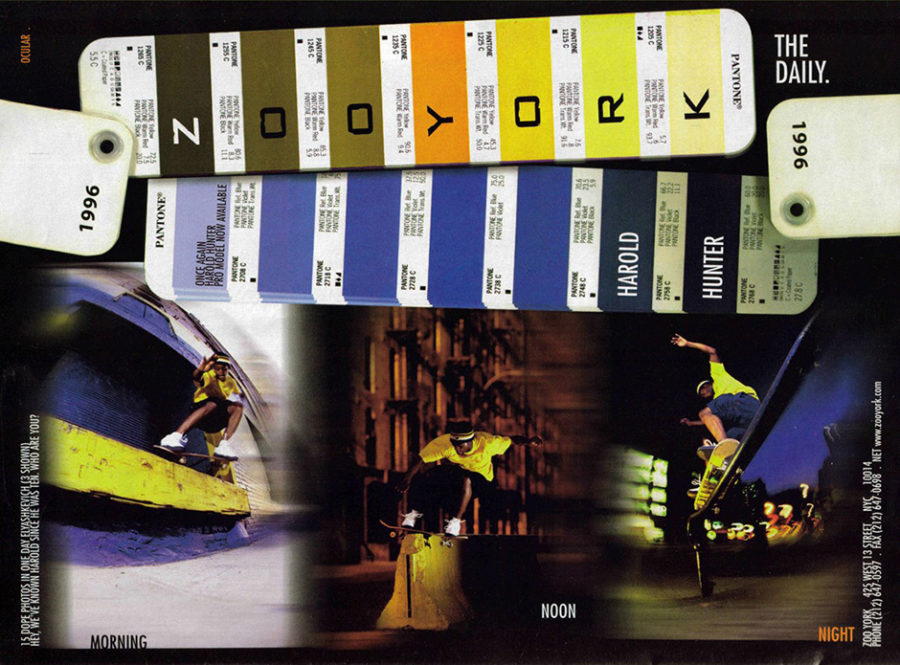

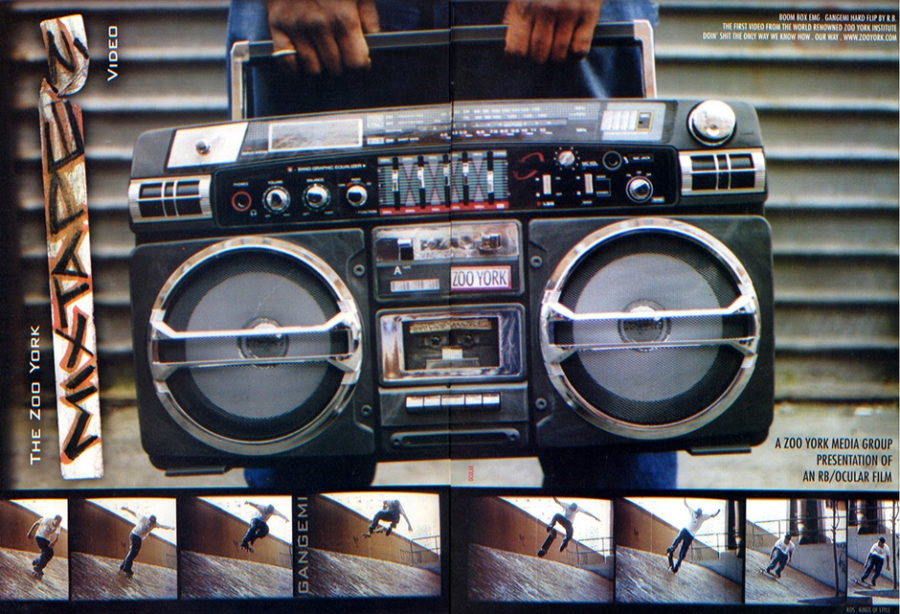

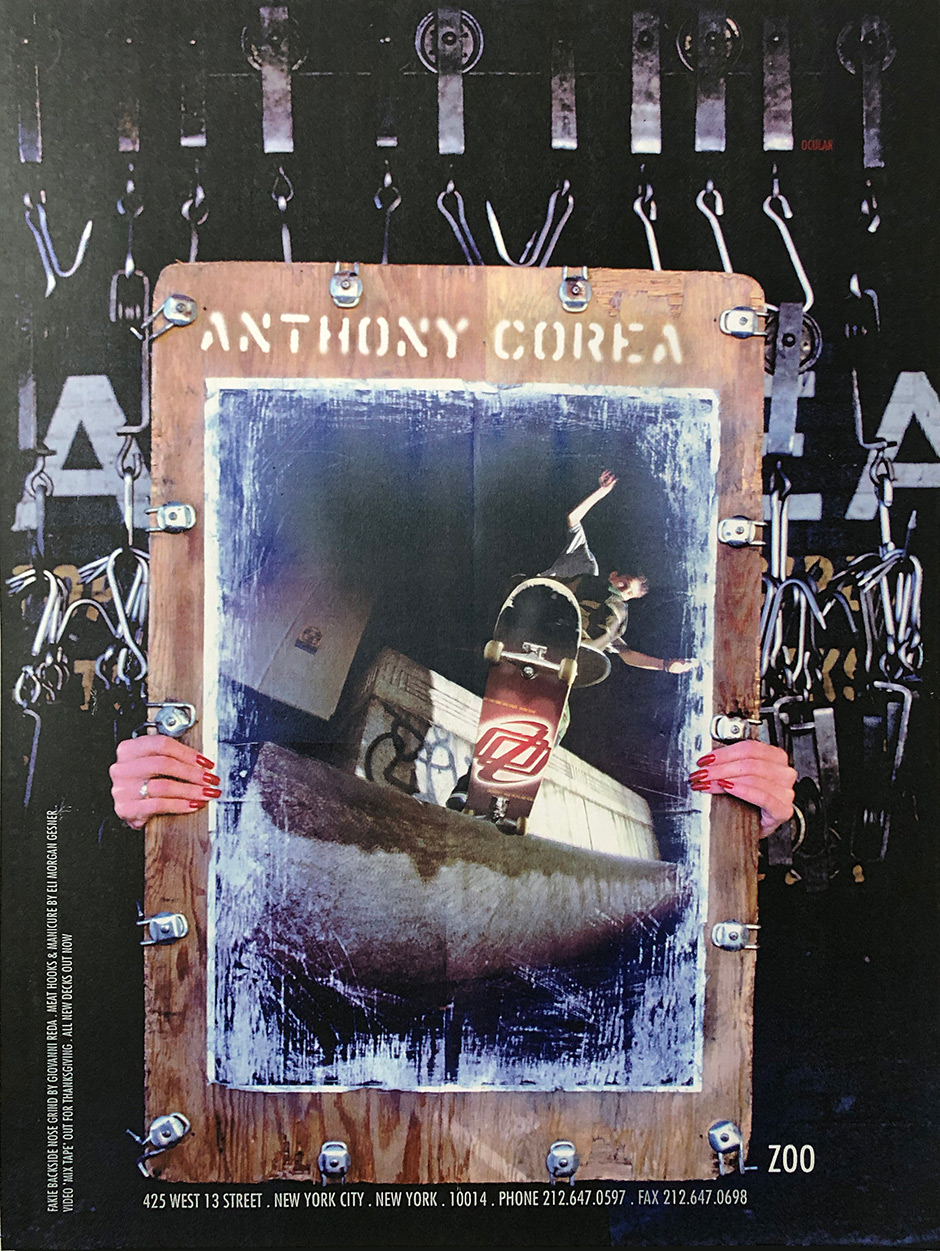

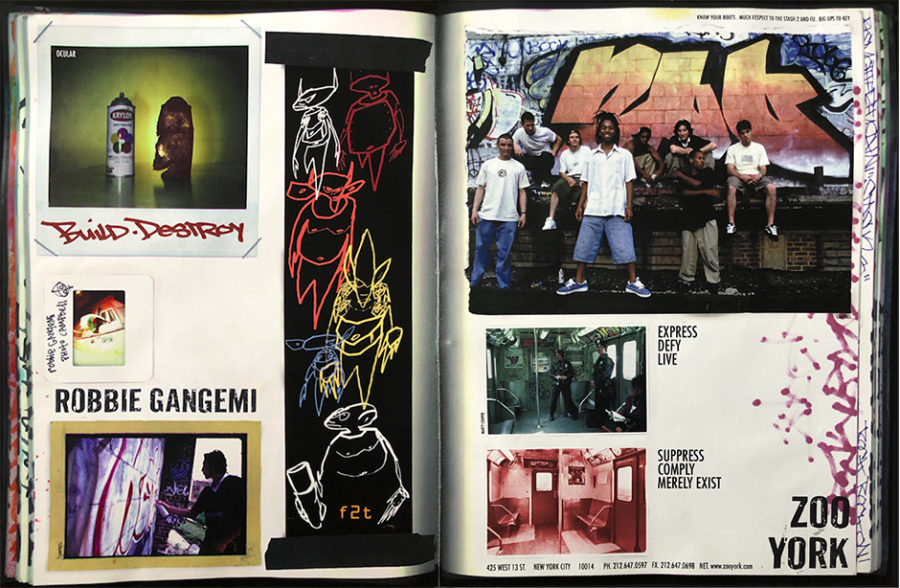

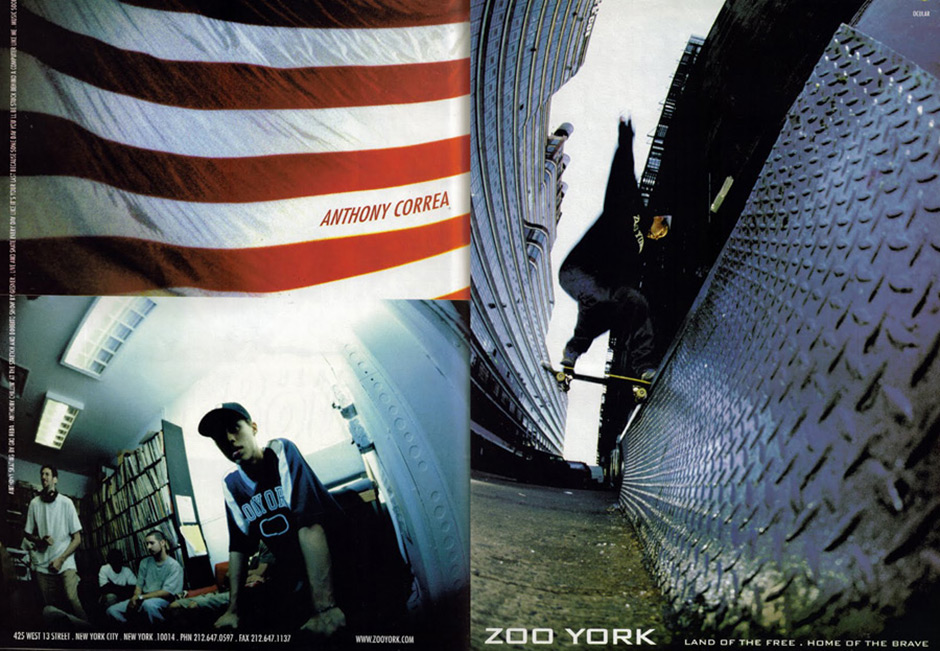

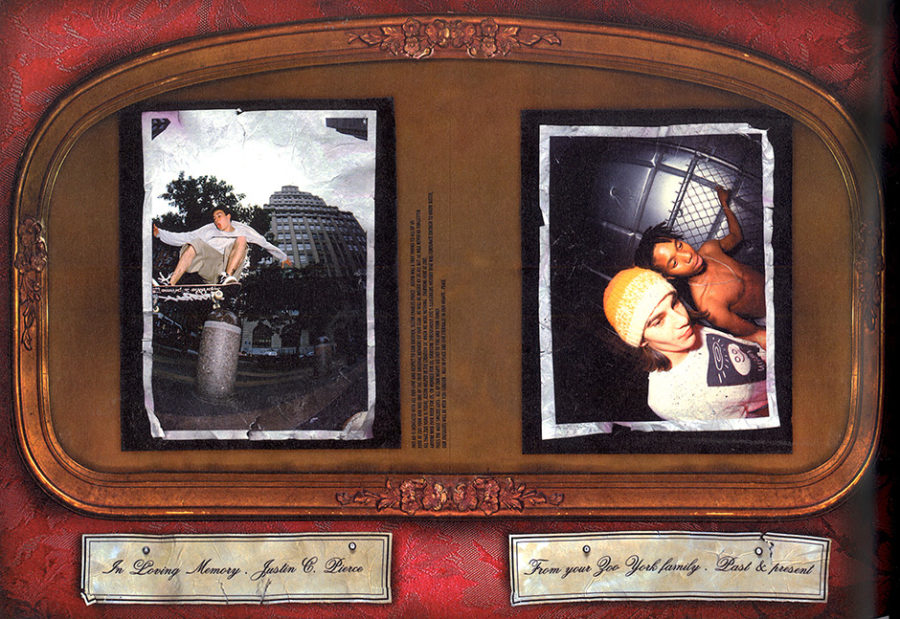

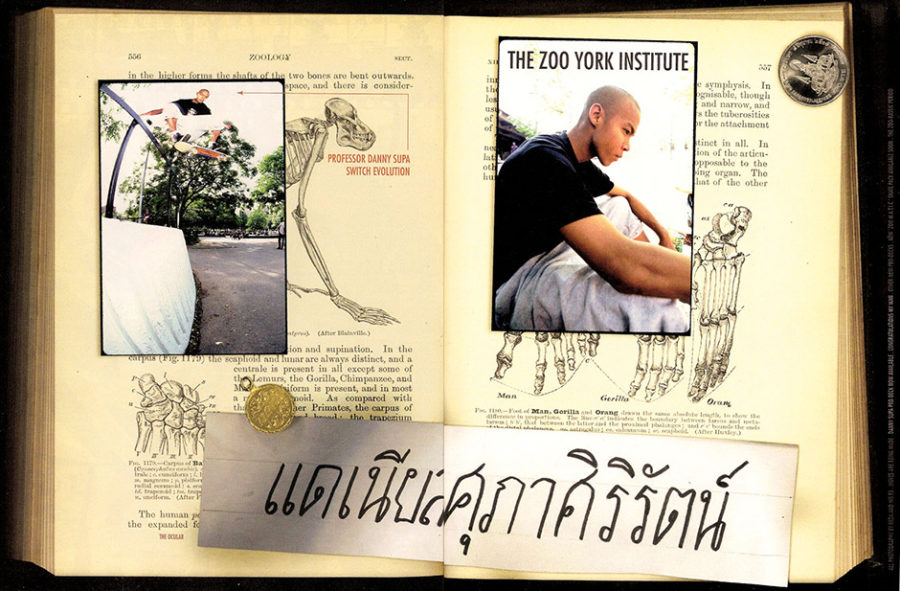

When Shut went out of business, Rodney got evicted, and I had that three bedroom apartment uptown so I let him come and live with me for a while. I was blessed with that apartment and always wanted to hook up my people. Around then Rodney told me he wanted to do another skateboard company, because skateboarding was going to make a comeback. This is at the point where nobody’s skateboarding. Rodney told me that Zoo York was the name that would put New York skateboarding forever on the map. I was 100% behind that. Rodney talked to Marc Edmonds and the original Zoo York crew, and asked if we could use the Zoo York name. Marc Edmonds gave us his blessing as long as we stayed true to Zoo York and got the name up. Very graffiti.

Rodney talked to Marc Edmonds and the original Zoo York crew, and asked if we could use the Zoo York name. Marc Edmonds gave us his blessing as long as we stayed true to Zoo York and got the name up

At this time computers were $60,000, so once I was part of Zoo York I used Russell Simmons by using the computers I made him get for me against himself. Photoshop and Illustrator, printers, everything I would need to start a company. He just left me to my own devices. I’d be in Def Jam Records or Rush Communications all night long doing Phat Farm stuff anyway, so when we started Zoo I would wait until everybody had left the office and call Rodney up and he’d come by and we’d stay up all night making Zoo York stuff.

Around that time, I still had some cache in the nightclub world, and there was a club called the Tunnel which was really popular in the ‘80s, that was being reopened, and Eric Goode—one of my design heroes—was doing the new interior design. I’d be excited to work with Eric Goode on anything he’d want to do…

Did Eric decide it needed a miniramp?

Ha, that’s what I’m getting to. Hahaha! So yeah, he wanted to put a miniramp in the nightclub, he wanted kids skateboarding in there and he wanted them skating in silver jumpsuits. Haha! To make a long story short, I got him to make a bigger skateboard ramp, one that would require installation, into the fuckin’ wall.

I knew he was always trying to mix it up and do things differently, so I knew if they made a little ramp they would just move it the fuck out of there, but if I could convince him to invest in this giant fuckin’ miniramp then we were good to go because they wouldn’t be able to get rid of it. It also had to be four feet off the ground because of architectural constraints, so he went for it because I showed him it could be used as a stage as well.

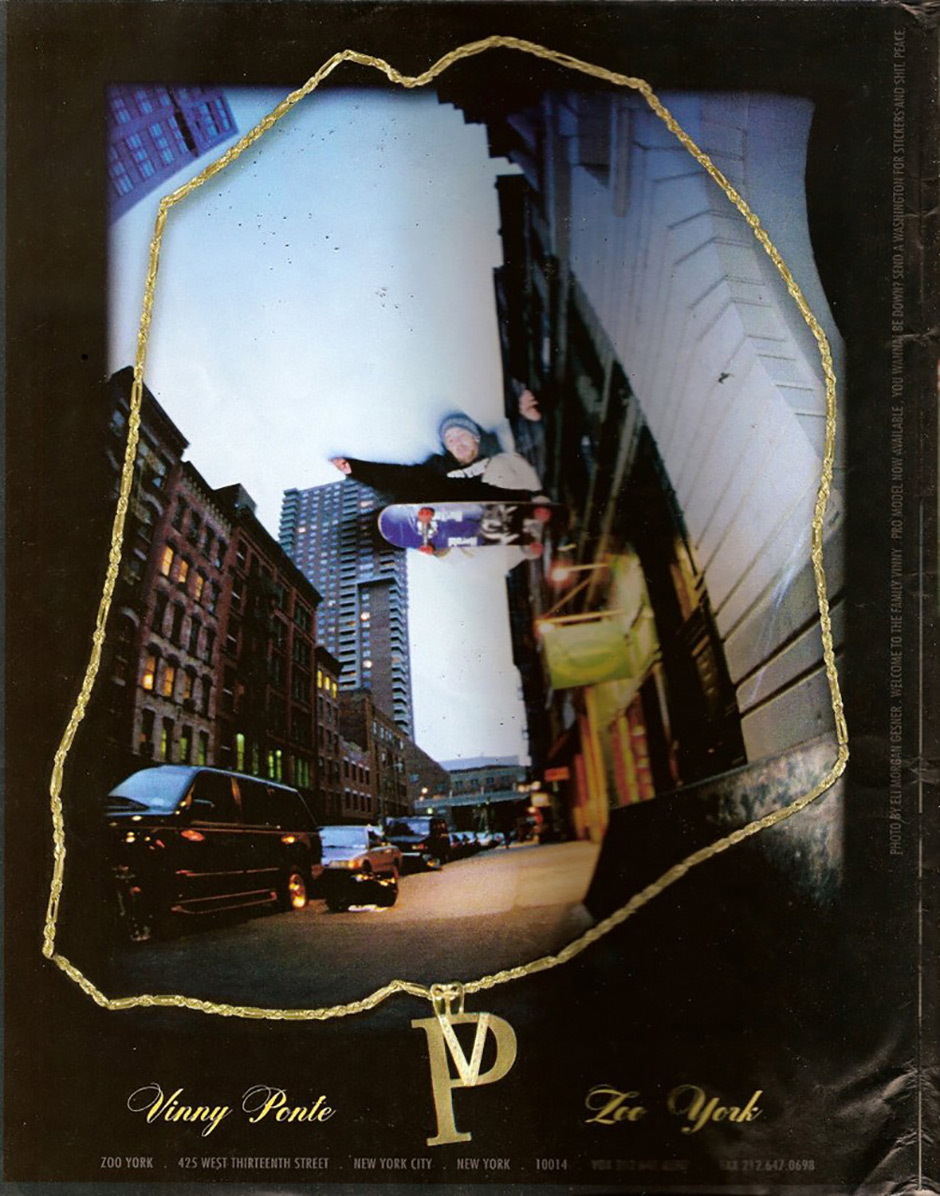

Eli backside ollies at the tunnel. Photo: Tobin Yelland

It was this magical time, still getting money from Phat Farm, staying up all night doing Zoo York stuff with Rodney and Adam Schatz and then we got ourselves a little warehouse in the Meatpacking District when it was still a shithole and the rent was dirt cheap. It was a wild time. The Tunnel thing happened so I got to build the ramp, and then all the skaters got hooked up at the nightclub, for years and years you could just walk in there and get free drinks and skate all night. It was like a dream.

And then I ran into James Jebbia who told me he was going to open a skate shop. Now, at this point there were no skate shops in New York City because nobody really skateboarded so I was stoked to hear he was going to make one. Then he said it wasn’t going to be a normal skate shop; he was going to open it in SoHo and it was going be like a White Box gallery, where the board graphics would be the artwork. So instead of going into a white gallery and there are paintings, you’re gonna go into a white gallery and there’ll be skateboards, and I thought that was fuckin’ awesome.

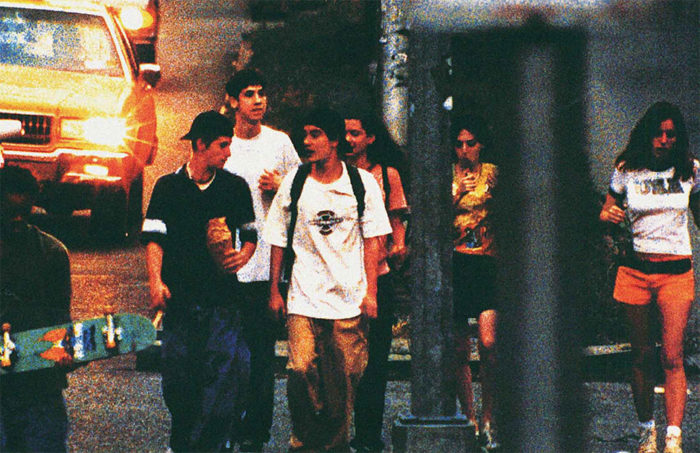

So Supreme happened, and everybody who skated for Zoo York would hang out there. Then we’d all go to the Tunnel to skate the ramp. Eventually Gus Van Sant, and Larry Clark, and Harmony showed up, and then Kids happened which ended up being this massive advertising blitz for Zoo York. Everything just led to the next thing, it was like a once-in-a-lifetime perfect storm of creativity and youthful energy.

then Kids happened which ended up being this massive advertising blitz for Zoo York. Everything just led to the next thing, it was like a once-in-a-lifetime perfect storm of creativity and youthful energy

Did you think that movie would be a big deal? There was a lot of good stuff going on then, so did it just seem like another fun thing to do and move on from?

No-one in it thought it was going to be what it ended up being. We just thought it was Gus Van Sant giving Harmony and Larry a chance to make a movie about everybody and we’d make some money from being in a movie. Fuck it, let’s do it, you know? No-one knew it was going to set everyone’s career off.

How true was it?

It’s kind of weird; the story about the person having AIDS and then running around having sex with people and infecting them without knowing it apparently comes from a real story. Before he made films Larry would document juvenile delinquents and their social groups, and in the ‘80s he was apparently hanging out with these gay Puerto Rican hustler prostitute boys on 42nd Street, and there are books about that, but I think that that really happened to one of those guys.