INTERVIEW BY NEIL MACDONALD (@SCIENCEVERSUSLIFE) / JEREMY ELKIN IN NEW YORK. PHOTO: Zander Taketomo

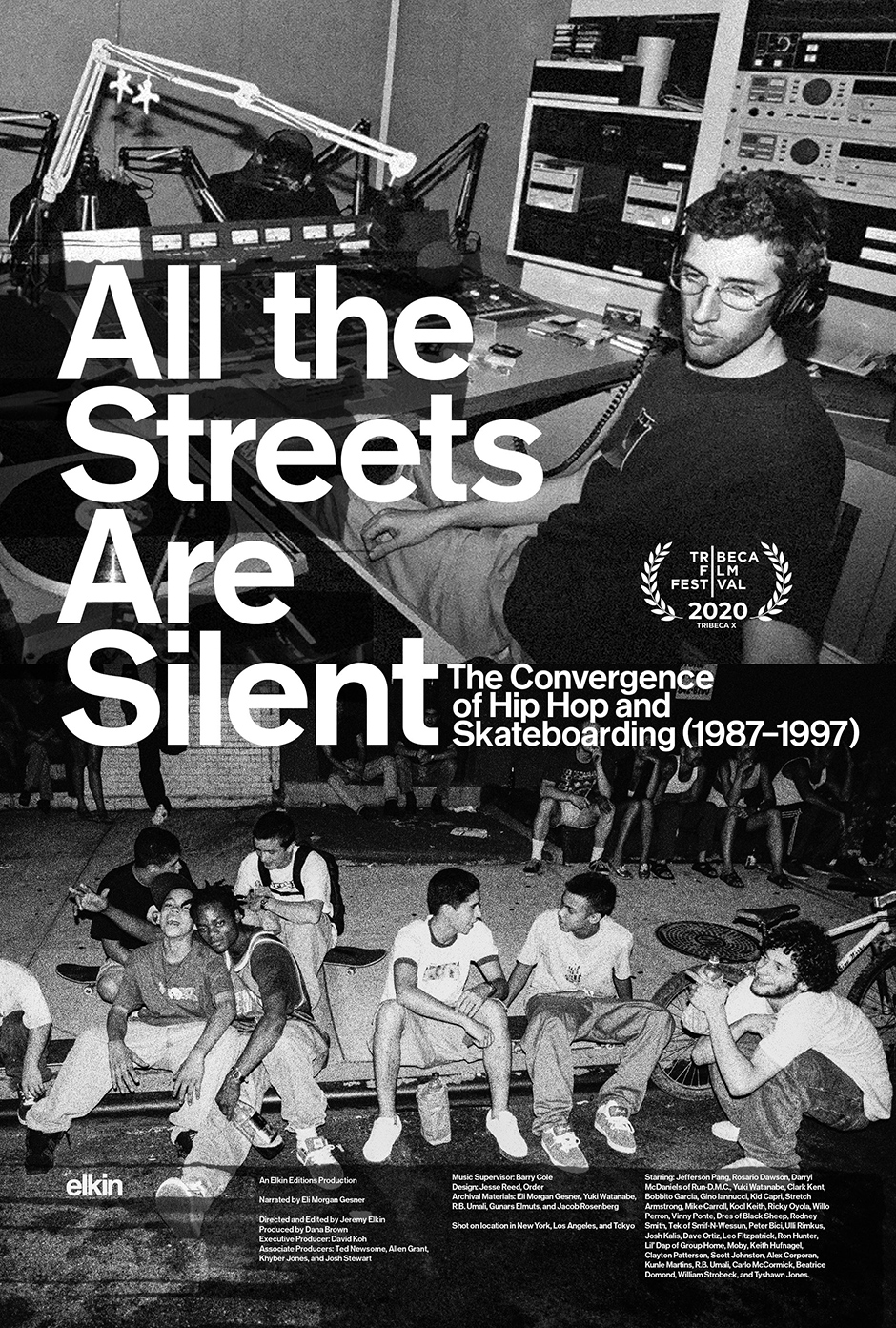

“Being at the right place at the right time has a lot to do with success”, Eli Morgan Gesner tells us in his opening narration of Jeremy Elkin’s All the Streets Are Silent: The Convergence of Hip Hop and Skateboarding (1987-1997), a CinemaScope documentary masterpiece that tells the story of one of the most important periods in modern history for New York—and therefore global—culture. It’s an observation that undoubtably applies to himself, as the skateboarder/artist/filmmaker who went on to co-found seminal NYC skateboard company Zoo York, establish Phat Farm for Russell Simmons and help introduce the notion of ‘streetwear’ (skate clothes for people who don’t skate) to the mainstream, but one that most certainly applies to Montreal-born skateboard filmer Elkin, who’s just completed what might be the finest piece of skateboard documentary filmmaking ever.

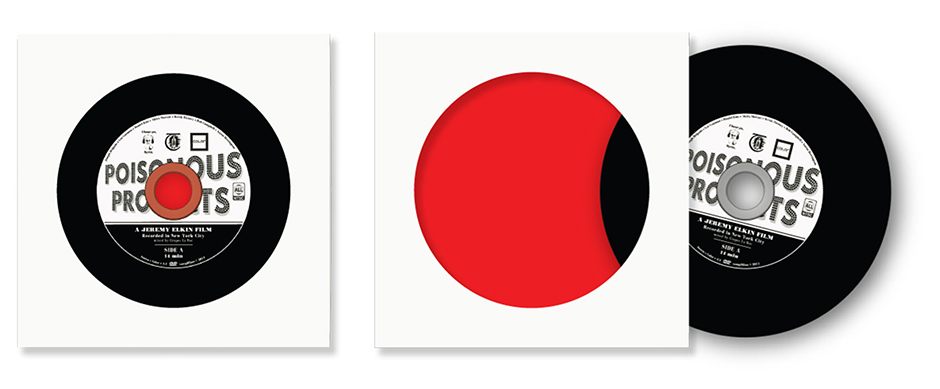

From shooting his friends skating in Canada and making the Lo-Def, Elephant Direct, Poisonous Products and The Brodies videos to working on Entertainment Tonight and for Vanity Fair, to directing this incredible film detailing the global significance of NYC’s skateboarding and hip hop culture, Elkin’s cultural contributions in his 33 years already outweigh those of many people’s lifetimes.

All The Streets Are Silent isn’t just an essential history lesson, it’s not just a trip through everything that happened over that decade, it’s the story of how skateboarding and hip hop met, progressed and evolved as told by the people who were actually there skating, making music, making clothes, changing things for ever. Creating a scene—and a sound, and a look—that would go on to influence what still plays on the radio and sells on the High Street across the world today.

Every bit as important to where skateboarding finds itself today as anything that happened in California, All the Streets Are Silent takes us from the crack-infested gang-run streets of Ed Koch’s late-80s Manhattan to Grammy awards, household names and a billion-dollar skate shop via a nightclub, a radio show, a Larry Clark movie, the Mixtape video, good clothes, real street skating and the skateboarders, rappers and DJs who made it all happen.

When some friends took the opportunity to play some hip hop at the downtown Mars nightclub, where sweaty skateboarders shared dancefloor space with models, movie stars and Madonna, everything changed forever. All The Streets Are Silent is the story, as told by narrator Eli, Kid Capri, Jeff Pang, Stretch Armstrong, Keith Hufnagel, Rosario Dawson, DJ Clark Kent, Rodney Smith, Moby, Yuki Watanabe, Gino Iannucci and Kool Keith amongst many, many others. It’s vital viewing.

You’ll be able to see the movie next year, so I called up Jeremy to find out how it happened…

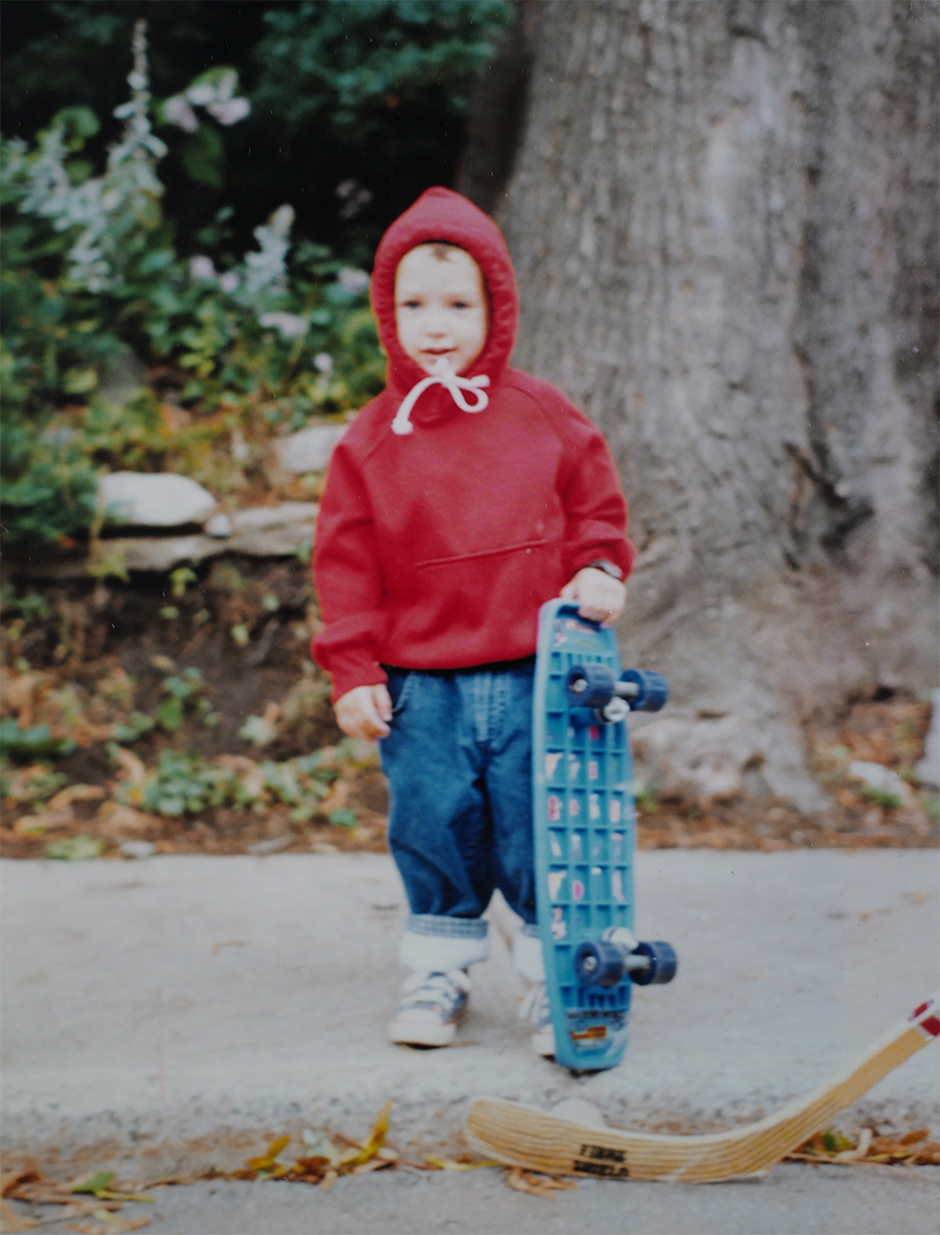

“There were always skateboards around thanks to my brother, Josh” Jeremy in 1989. Photo: Marilyn Elkin

What’s going on man?

We were just celebrating one year of successfully saving Tompkins Square Park from becoming Astroturf. Adam Zhu organised it, and got everybody together to hang out, raise some money for a good cause and help support local businesses that are struggling during the pandemic. I shot some moments for All the Streets Are Silent there.

How has it been for you during the pandemic? You’ve got a movie to get out there.

It’s been tough to get the film made during Covid. We’ve been taking our time and it’s been nice to look at the doc with fresh eyes, make necessary tweaks and try to keep pushing forward, even though we’re in really different times relative to how it was six months ago.

The movie was meant to premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 19th, and we had this party planned with adidas Originals featuring an all-star lineup of MCs and DJs. That was months of planning, so to all of a sudden have that not to be the case was pretty heartbreaking for everybody involved.

What videos got you into filming skateboarding in the first place? What got you hyped back then in Montreal?

There were always skateboards around thanks to my brother, Josh. He’s fourteen years older than me, and he’s an artist, DJ, etcetera, and in the ’80s he was really connected to the microscopic Montreal skate scene. Him and my sisters—and their crew of friends—were going to clubs, skating, listening to the latest records and going back and forth to New York, and because I’m so much younger than my siblings I just took that for granted and thought it was normal because that’s what I was surrounded by. It wasn’t until I was way older when I realised that was actually unique.

Jeremy’s siblings Sarah, Josh and Lisa in 1998

My brother skated but he wasn’t really watching skate videos. It wasn’t until I was over at one of his friends’ house, in what must have been 1997 or ’98, and they were watching Rodney vs. Daewon. That’s the first video I remember. I’d seen videos before, but they were vert and snowboard videos, which didn’t interest me. I wasn’t skating much, I mean I could get up a kerb, but some of your falls are really memorable when you’re young and I’m a really cautious person so I wasn’t jumping down stairs at that age, like a lot of kids do now. Montreal winters are gruelling and there were no skateparks where I grew up, so I didn’t skate a park until I was about 16, I think.

But you were in amongst it.

I grew up skating street downtown and traveling back and forth to New York, however we could, but I wasn’t really watching skate videos and I wasn’t really interested in film, but I’d always skated at this spot called The Pond, on the west side of Montreal after school. Lucas Wisenthal was a local; he’s at Complex now and was/is a true skate nerd. Tyler Maher too, who was in the North videos, and all these other locals who were super good, but video-wise it was a bit of a blur for me until Menikmati came out.

I’d been filming skating since about 1999, since I was 12-ish, but I was filming people with no end goal. I was shooting because I thought what they were doing was amazing, but I didn’t know what a pro skater was. I didn’t know the difference between a lipslide and a boardslide, you know? We didn’t care because we weren’t concerned with the details.

For my grandmother’s 100th birthday, she wanted to get each of her four grandchildren a digital video camera

But you had a video camera around. Were you doing that at school or something?

I definitely wasn’t doing it at school… For my grandmother’s 100th birthday, she wanted to get each of her four grandchildren a digital video camera. This was when digital technology was brand new, and these were some of the first consumer ‘digital’ video cameras, even though it was still tape stock. So she got me a little digital Nikon 775 point-and-shoot, which had a video mode with no sound, so I got a little sound recorder and would record sound separately, and then match it in post. But, I mean, the videos were like 200 x 100 pixels. That was my first experience of making skate videos, on that thing, and I thought that was normal because no-one had video cameras.

I always loved how happy we were when we would finally landed tricks, so I was collecting footage, then Menikmati must have come out. What year was that?

2000.

Right, so when Menikmati came out it was this revelation, like if you collect enough footage you can produce a video. I was really into collecting; I was collecting everything like cards, stickers, stamps or things I’d find, so I thought if I collected enough tricks of friends I could make a skate video. I had no idea who any of the skaters in the éS video were, it was all brand new and I wasn’t interested in the industry side of things, I just liked the skateboarding.

As was the custom, back then.

Yeah! So that was a really big moment. I wound up getting a better video camera and making my first actual video, which I think came out in ’03. I say “came out”, I mean I burned a bunch of DVDs—which at the time was futuristic—for the people who appeared in the video and for some friends. I think I made fifty of them before I damaged the DVD burner.

I’d never been good at making ‘objects’, so it was interesting to me that if I collected enough footage and if it was good enough, then I could make this object that I could then give to people. I thought it was a fun thing to do, and nobody was doing it in my neighbourhood. I wanted to do something that no-one was doing. I did another short video that came out in ’04, and kept filming.

A skate shop opened up in the west side of Montreal called Alena, which was awesome. It kind of had the Supreme aesthetic at the time. I remember coming back from New York as a little kid, after having been to Supreme, and had people asking why I was wearing the shirt of a New York skate shop. Supreme was the only place in SoHo like that, I think. Air conditioning, crazy music you’ve never heard before that was so loud that you can’t hear the person working there, limited stock, no carpet… This weird, futuristic version of a skate shop that looked like a gallery, and Alena was that for the west end of Montreal.

Supreme ad from 1994. Photo David “Shadi” Perez

When did you realise you could make videos and get paid for it?

So we had the shop, Alena, but the scene in Montreal was tiny. There was Temple Skate Supply and Underworld downtown, but those seemed like they were super far away. We were only familiar with our little pocket of the city. So I kept making videos, I kept taking photos, and eventually met people outside our friend group. It blew my mind when Jeremy Pettit came to my neighbourhood to film for North 2. He was shooting 16mm, and filming with a VX, and which was crazy to me.

Another person who was around and helped me out when I was a kid was Raj Mehra, who does Mehrathon distribution now. He was distributing Zoo York in Canada at the time, and he said how we should get Zoo to sponsor a video I was making at the time. The thought of getting paid to make a video was crazy, and when they asked how much I’d need I remember saying something around $1,000, because I didn’t know what to ask for. I don’t know what the number was but it was low for a two-year project! Haha! It was really weird getting that money because I was a little kid making a skate video. That moment shifted my perspective.

To one where you realised that you were doing this well enough that people were attaching a financial value to it?

Yeah. I think that project that Raj helped with, Floorwork, was released in ’06 or ’07. It was a Montreal video, but we would come down to New York to film as well. A lot of the guys in it went on to start Dime. They were called Dimestore at the time, although they didn’t have a store, then they renamed it Dime, and now have a store.

Who were you filming in New York?

N.Y. was a bigger, shinier version of Montreal that had fresher music, different style and everything was in-your-face, which is all really impressive when you’re a kid, but the environment is a similar vibe to Montreal which made it familiar. The style of the cities are the same.

I’d come down with friends from Montreal and we’d skate the Banks, or we’d go to Tompkins Square Park or whatever. Discovering Tompkins was a big moment. I knew about it from R.B. Umali’s Vicious Cycle video but I hadn’t been there until right after that video came out. Everything was new and it represented the future to me.

Discovering Tompkins was a big moment. I knew about it from R.B. Umali’s Vicious Cycle video but I hadn’t been there until right after that video came out.

It’s interesting you mention going to the Banks, and then how stoked you were to get to Tompkins. Were the Banks not a big deal?

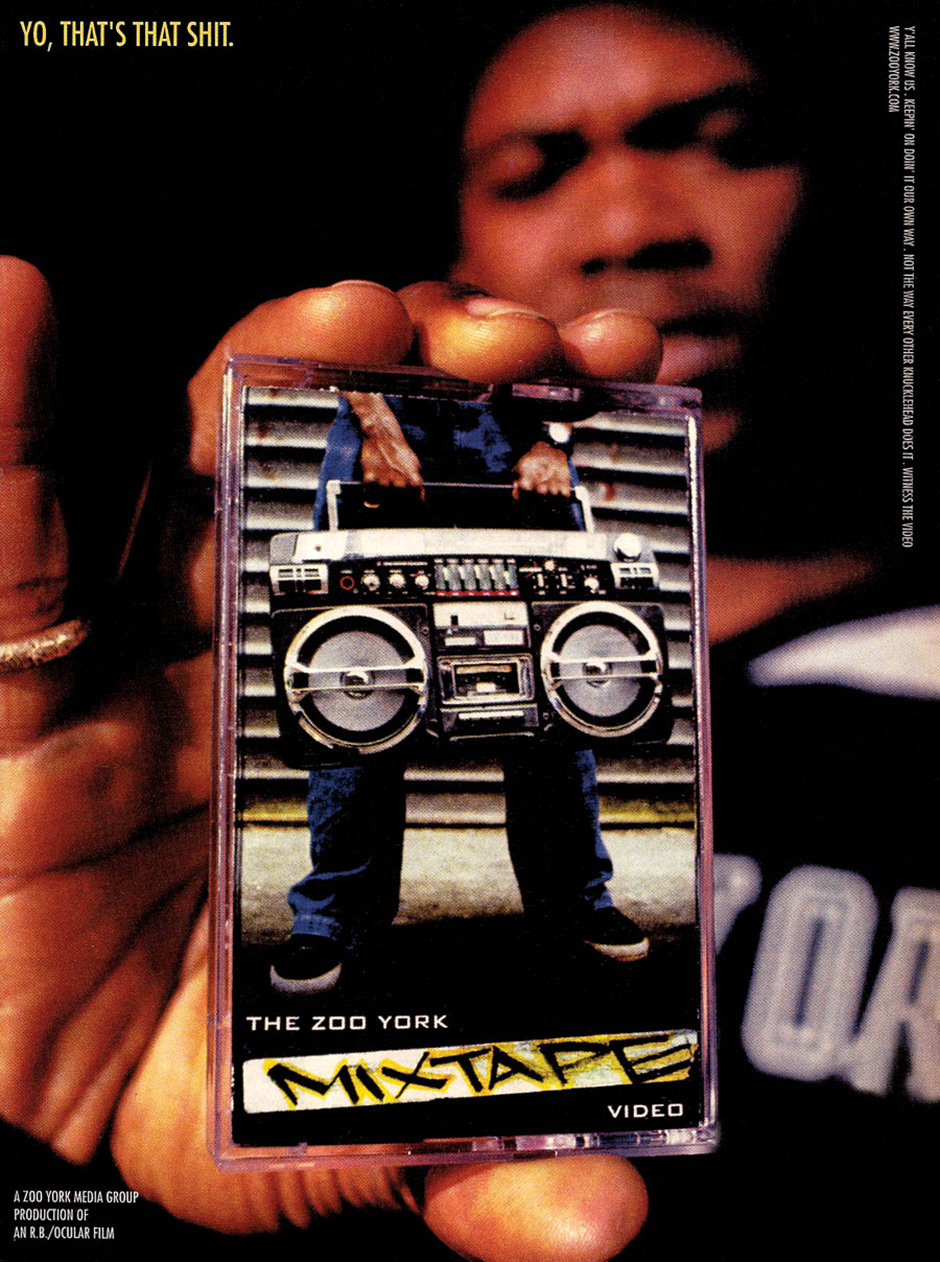

I didn’t grow up skating transition, so it wasn’t that appealing to me, and the Banks weren’t the focal point of the videos that I liked. At that time the golden era of Banks skating had passed. Even the first Zoo York video that I was exposed to wasn’t Mixtape. I didn’t see Mixtape until way later because there was no access to it. There was no YouTube, and you’d ask in a skate shop and get told they had sold out years ago. Videos were really inaccessible and in Montreal they were expensive, so if you’re only making a little bit of money you had to judge the video by its cover because the cool guy in the skate shop isn’t going to rip open the plastic and put it in for you.

Jeremy didn’t get to see this video till years later. One of the best covers of all time. Mixtape ad from 1998

Nostalgia is pretty new in skateboarding. Nobody in, say, 2003 was wanting a video from a couple of years ago because it was pretty much all about new stuff then. I’d guess that an EST would have been the first New York video you saw, since the Zoo videos weren’t anywhere you could see them.

I think I remember seeing EST 2 or 3, but I guess that would have been my first New York video I saw. Around the time Vicious Cycle came out, so ’03.

It’s funny because at the time I wasn’t really into skate videos, because the ones I owned were all really bad. But then Yeah Right! came out and I got hooked on them. That was a huge eye-opener. Those skaters looked way cooler than the skaters I was used to watching in videos, and the way it was put together was amazing… The whole vibe of it was also less serious than what I had seen.

From a technical point of view it pushed what skate videos could look like too. That must have been inspiring.

Yeah. I watched that tape a billion times. It had a huge impact on me and my friends. Accessibility was a big issue then. Even when YouTube started in ’05, ‘90s videos weren’t on there. There was no way to see those old videos, even though I knew there was a huge catalogue of skate videos in the ‘90s because Transworld, etcetera would reference old videos in their magazines, but they were like these lost artefacts.

Lo-Def filming squad. Phil Knechtel, Ryan Decenzo, Andrew McGraw, Jeremy Elkin. Photo: Geoff Clifford

So in 2007 you made Lo-Def.

I was making skate videos but I wasn’t happy with what I was making, up until, I guess, ’06. It was kind of like my film school I suppose, because there was a lot of trial and error involved and I wasn’t ever happy with the result. I changed my approach for the Lo-Def video. YouTube was out by then, and skate videos at the time were all somewhere between about thirty-five minutes and an hour plus, so for the Lo-Def video I made it about fourteen minutes and I put it online rather than selling it or getting a distributor, even though I had Sandro Grison and Color Magazine to help promote it.

Having those Vancouver guys backing what I was doing was mind-blowing to me. Lo-Def found an audience right away—the comments on Vimeo and on Slap at the time were positive. I made a website for it, and called it ‘Xamplfilms’ because you’d hear fables about record labels coming after skate brands for money, and I wanted some made-up name that wasn’t attributed to me, so I could try to get away with it, I suppose.

Slam has a lot of love for Kevin Lowry. Downtown ollie for Lo-Def. Photo: Geoff Clifford

How did you end up getting footage in the Static videos?

I sent some copies of Lo-Def down to Josh Stewart, because I was obsessed with his Static videos. Static II, especially. He gave the copies out to people who ordered from his site. I could kinda tell that he was genuinely psyched and he wasn’t just gassing me up, so when I wrote him back I told him that if he ever needed anybody to film in Montreal, I’ve got it, which of course never happened.

You basically sent a filmer your filmer sponsor-me tape.

Ha. I guess so. Haven’t really thought about it like that, but I basically learned how to film because of, I would say, Jason Hernandez, Ty Evans, French Fred, Eric Lebeau and Josh Stewart. Those were the guys I looked up to as a little kid, and I’m now somehow friends with all of them. It’s very weird but that’s how it works, I guess. The skate world is tiny, especially 15 years ago.

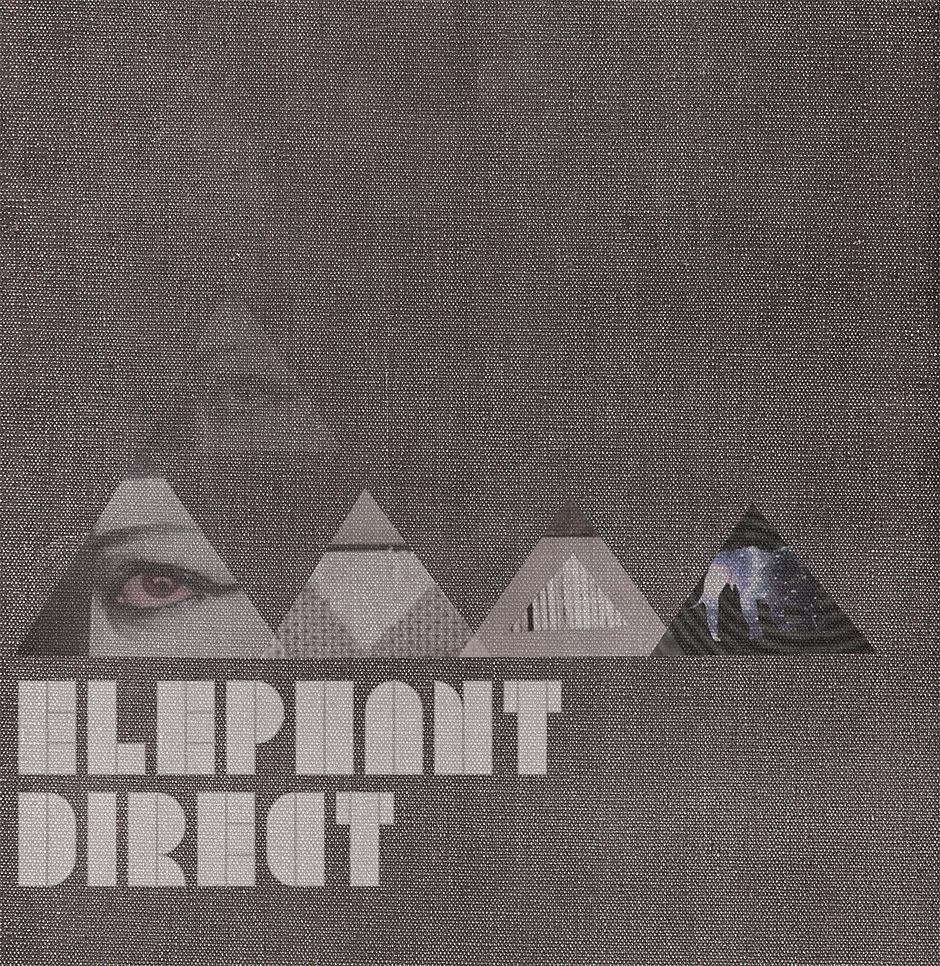

After that I made another video called Elephant Direct, a two-year project that came out in 2010 and that was received better than I could ever have expected. Super good times working with Jason Auger and everyone else who contributed footage. People still take photos outside the Montreal store that it was named after, and it’s cool that Canadian skaters gravitated towards that video. It was an honour that people I look up to liked it. We premiered that video while I was sort of already in the process of moving down to New York.

Torey Goodall outside elephant direct in 2009. Photo: Kasey Andrews

Were you moving to New York City to film skateboarding? Was it a big enough deal by then that it was worth relocating?

I wasn’t making any money and it costs a fortune to live in New York, so I was still just doing it for fun, really. I was living on my brother’s couch, but then randomly got a place with a VICE video producer, which at the time was called VBS. Liz was super cool, we had mutual friends and I’d met her in Montreal once or twice. She lived in Greenpoint and needed a roommate. During my first week living there, I didn’t really know Josh, we would just send each other mail, or email—I randomly ran into Josh. He lived a couple short blocks away from that apartment.

VICE is from Montreal too, but that’s a pretty fortuitous living arrangement… Staying with somebody from VBS and then your favourite filmer down the street.

Yeah, Josh asked what I was doing there, and I said, “Nothing”. Which in hindsight was so true. I should say that at this point I’d already filmed with Leo Gutman, Taji Ameen, German Nieves, Rodney Torres, Billy Rohan and all those dudes in the early/mid 2000s, and a lot of them had appeared in past Static videos, so I figured that if I filmed with those guys I could give Josh the footage. I was already used to the routine of filming long days. Unless you were physically unable to go outside, then we were filming because I wanted to get better at it.

Static IV filming equipment. Jeremy’s VX1000’s. Photo: Jeremy Elkin

I think skaters saw that I was down to film all the time, so I ended up getting three, four or five useable clips every single day because that’s what I was used to doing in Montreal

The filmers in New York at the time weren’t filming like that, they would go to Tompkins and chill, then maybe get a sandwich, then skate for a bit, then maybe grabbing a camera to film Jake Johnson or whoever, but they weren’t really filming how I was used to filming but they were infinitely more skilled at it… I think skaters saw that I was down to film all the time, so I ended up getting three, four or five useable clips every single day because that’s what I was used to doing in Montreal. If the skater got too tired I would just go meet up with someone else until they got too tired, then I’d go meet up with another crew at another spot and skate all night. It was an organic thing, which I thought was normal.

A lot of people move to a new place and decide they’re going to make a video around that place, but you’re not really a local, you’re a tourist. And the conversation behind your back is always like, “Is he going to stay, or is he just here for a year or two?”, but I was always clear that I wanted to live in New York…

So you’re giving Josh the footage that you’re getting.

Yeah. And I was filming a lot with Aaron Herrington, who had just moved here from San Francisco, and I knew through Brian Delatorre, and Josh was like, “Who is this guy?!”, because I wasn’t labelling the skaters, so I told him he’d just moved from SF, but all that footage ended up in what became Static IV.

What were you doing for money?

I was living in a six-storey walk-up, with Paul Seaholm, paying almost no rent. It had a communal Chinese bathroom in the main hallway of the building. I was working at a café a couple days a week called ‘sNice. Bobby Puleo, Josh, Aaron, Delatorre, Yaje [Popson], Jack Sabback and Rob Harris all worked there at some point, pretty much every skater in New York at some point worked for Mike and Deb, who are amazing people. Big props to them for helping so many skaters out.

For about two years, one or two days a week I was working as an assistant camera/lighting tech at Entertainment Tonight, I was doing two days a week at the café and I was filming for Static as well as my own independent videos, Poisonous Products and The Brodies.

Did you study film, at some point?

No, I didn’t go to university or anything like that. I moved to New York instead.

Right on. You’ve done a lot, considering.

During the two years I was working on Entertainment Tonight, working at ‘sNice and filming skating, I was doing freelance jobs for Nike and VICE, through R.B. Umali and others. It was freelance production, but I was transitioning a little bit into more elaborate forms of it where it wasn’t just me sitting in a gutter in Queens, it was going to a studio, which was a massive change from the field.

I was still very much doing the Static thing, when I got a call from Greg Weinstein, a downtown N.Y. character, to help start a video department at Thrillist—and the talent working with them was an up-and-coming comedian called The Fat Jew. He now has millions of Instagram followers, but then he was just a local comedian, basically ‘on-air talent’ for Thrillist.

We’d interview a different rapper every week, and it was kind of a weird job because we kinda did whatever we wanted, thanks to Josh, The Fat Jew. It was really loose. So it was cool, it was like a fake ‘first corporate job’ for me because it was a corporate job, but it was very un-corporate. I made a ton of videos in a short time with quick turn around and sort of learned how to direct and manage a bigger production. We’d shoot an interview one day and it’d be out the next morning.

Jeremy job juggling to film Jason Spivey for the brodies. Photo: Pep Kim

Sounds perfect. What came next?

Well I quit that job after being there for about six months or so, when the parent company started to change, but I met some really good people there who I’m still friends with. It was a full-time job, so I’d be working nine-to-five, then meeting Akira Mowatt or whoever out the back to go film. It was actually right behind Supreme, so when I was filming for The Brodies and Static I was meeting up with skaters outside of my workplace.

But yeah, it wasn’t chill anymore and Fat Jew was trying to leave. Instagram was just starting, and I remember thinking it was crazy that he had five thousand followers. Right away he was posting crazy, dark web content and getting tonnes of followers. Posting memes before we knew what memes were. I think he was the first actual ‘influencer’, he was the first person getting sent product to post on Instagram.

Akira Mowatt filming for the brodies. Photo: Jeremy Elkin

And then how did you come to work at Vanity Fair?

I applied online and was given the job after a month of video sample tests but I had no idea what I was about to walk into. That was a mind-blowing experience. From the start I was on set with celebrities and in charge of the future of video production for a well known magazine.

I worked under my boss Dana Brown’s direction who is actually now my producer for my documentary. With Graydon Carter in charge, there were editorial legends from the New York publishing world everywhere, and the level of precision and detail everyone put into it… I was working on projects with crazy perfectionists whose production values were through the roof, and craft-driven. It was super inspiring to be around all these incredible people, which was the complete opposite of Thrillist or Entertainment Tonight. At Vanity Fair it was more like, “We’ve been working here for thirty years and we’re not gonna sleep until the story is done”.

That first year was so eye-opening. Even in the first week, sitting in the office and seeing Jony Ive walk past my desk… It was like being in a spaceship.

view from the spaceship. Vanity Fair office New York. Photo: Jeremy Elkin

That’s a big difference from sitting in a gutter in Queens.

I should say that I totally abandoned skate filming after Thrillist and releasing The Brodies, because when I accepted the Vanity Fair gig I realised I couldn’t just show up during the day, work for ten hours then go film skating, I had to basically sleep there for the first year or two. I was 27, coming into a place where I’m surrounded by people in their 40s, 50s and 60s who had been there for decades. It was a family.

It was a seismic shift in my mentality. This beautiful, slow, methodical production versus a rat-race tech company

There’s a huge level of secrecy, of confidentiality, involved that was lightyears beyond anything I had ever worked with before. At Thrillist and Entertainment Tonight we were chasing the news, and at Vanity Fair we were creating the news, through each editor’s relationships. It was a seismic shift in my mentality. This beautiful, slow, methodical production versus a rat-race tech company. I had the freedom and the trust from Dana, Graydon and all my colleagues there but for the first year I was the only video department employee.

From making the Brodies to an Amy Schumer shoot for Vanity Fair. Photo: Jeremy Elkin

What did you actually do there?

Each month we would make a documentary, or a behind the scenes cover video, or an interview or a feature on a subject in the upcoming issue of the magazine. The deadlines seemed really spread out, where I’d have three weeks to work on one thing, so I could make things I was actually really proud of and really focus on the craft like I had done making skate videos. I definitely owe everything I’ve achieved to Raj Mehra, Sandro Grison from Color Magazine, Josh Stewart and Dana Brown.

Do you think it was being able to work capably at that level that inspired you to make All The Streets Are Silent?

When V.F. started going in a different direction at the end of 2016—when I quit—I took a break then started my own business, Elkin Editions, which is the label the film is being made under…Commercial video production, editorial, etcetera.

So that stuff is going on while you’re making the documentary?

Yeah. There’s a lot on our plate right now.

Eli Morgan Gesner interview for All The Streets Are Silent. Photo: Jeremy Elkin

How did you meet Eli?

I met Eli Gesner when he did the hand style for The Brodies in 2013.

He’s a good dude.

Eli’s super dope and an amazing artist. It takes a certain person to develop a brand like Zoo and make those videos… And music! It’s really remarkable what he’s accomplished. I knew most of his background, but there were missing components to it that I couldn’t believe, which led to the early days developing the film with his archive.

I normally do things pretty quickly, but when it’s a large scale project I tend to approach it with extreme caution. I’ll usually play it safe, so when the idea to make a Mixtape documentary came up, I wanted to ease into it over months and months and really learn how it happened, before I could get comfortable with making it.

I’m surprised you’ve got the space in your life to be able to slow anything down.

If you keep pushing hard at something, you might get somewhere, but there’s also a level of luck and serendipity associated with that persistence. It’s who you know but it’s mixed with luck, and what you’ve made. I’ve gotten pretty lucky in my life. That’s what it comes down to. And Eli was another one of those moments.

When did you finally see Mixtape?

Yeah, I think I saw Mixtape for the first time on Vimeo or on YouTube in 2007, or ’08. I only watched it because Sandro had said Lo-Def was “sort of like Mixtape”. I didn’t agree, but thats because I was thinking of the first EST. He sent me the link, and I was in awe. Along with Static II, those were the two coolest skate videos ever, you know? At least to me.

So to rewind, in summer 2017 Leland Ware who did 48blocks hit me up. We were on the roof of the 169 Bar on Canal Street with a bunch of people, and Leland told me he was working with Ben Oleynik—who was brand manager for Zoo in the 2010s—because the 20th anniversary of Mixtape was coming up and Zoo wanted to hire us to make a short documentary on it… I could be getting this story slightly wrong, but anyhow…

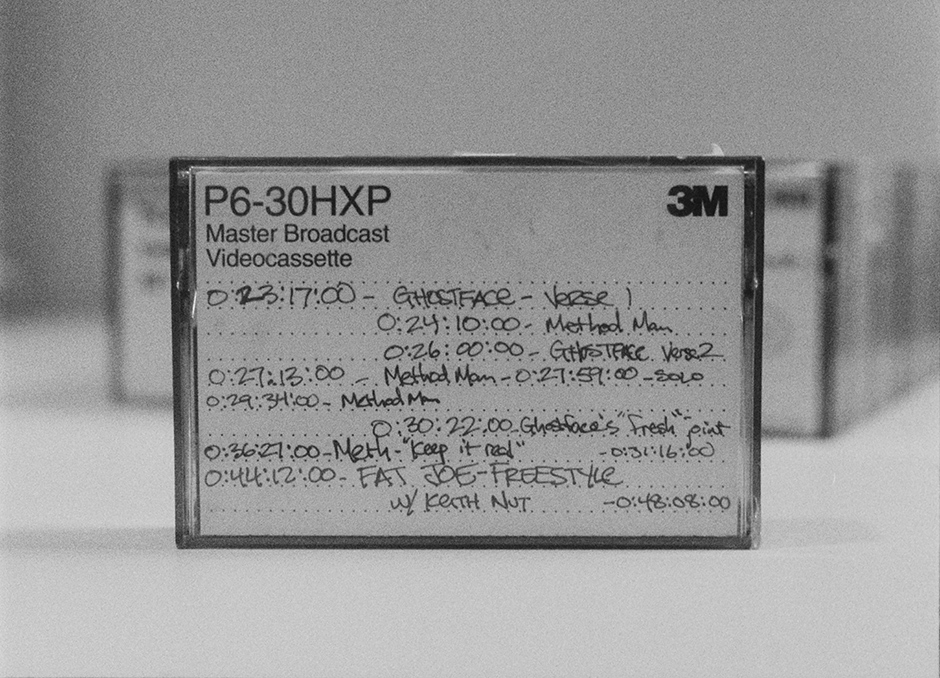

My first thoughts were that R.B. Umali had just left Zoo and Eli had left Zoo after 9/11, so that’s already not a good first step in terms of relationships with the new owners. A lot of the riders from back then were over what Zoo had become, and I had a feeling that the rappers would want a lot of money to be in it! So I didn’t know if it would even be possible. And also, in the time I had, how was I going to go through thousands of tapes?! They had the hi-res version of the video, and they had wanted me to put some interviews in there and make a retrospective, which I thought sounded terrible.

Life changing Hi-8 tape. Photo: Zander Taketomo

Those are some pretty significant reservations.

Those were my first thoughts, but I kept an open mind and asked Eli and R.B. I remember suggesting that me and Leland—who’s a producer anyway—just make it together. I’d talked with Eli and R.B. about maybe doing it independently, and they were cool with that, as long as the holding/licensing company of Zoo was not involved. So I outlined what I wanted to do, if we were going to do it properly.

I’d need a couple of years, I’d need all the original footage and we’d need to sit down with him and do a full interview before we actually interview him, and he thought I was crazy. Haha! He said that if he and R.B. gave me all their footage, they’d want me to digitise all the best clips on those tapes, which was no problem, but I didn’t realise what I was walking into, because that eventually became All The Streets Are Silent.

He said that if he and R.B. gave me all their footage, they’d want me to digitise all the best clips on those tapes…but I didn’t realise what I was walking into, because that eventually became All The Streets Are Silent.

So that’s where it started.

Yeah, we started doing interviews fall 2017. The first ones were Alex Corporan and Spencer Fujimoto, on the same day. We did 53 interviews for the movie, and I think I used 24. I wanted to do one interview a week until we were finished. We knew a lot of the interviews would be cut but we went down that rabbit hole; I wanted to interview everybody or I thought the story would suffer and lack depth.

I actually have a list of interviews that were refused, and then a list of people that I never heard back from, a list of cut interviews and a list of dream interviews where it was people I was probably too scared to ever email! Haha!

dream interview territory right here. Kool Keith. Photo: Jeremy Elkin

I wanted to ask you about this. It seems to me that pretty much everybody you’d hope to see in that film, is in that film. Who did you speak to that didn’t go in?

Some of the cut interviews that we did not use are Taji Ameen, Bowery Bob, Spencer Fujimoto, [Gio] Reda, Ian Reid, Rodney Torres, Zered Bassett, Danny Supa, Anthony Correa, Jim Power, Adam Schatz and Akira Mowatt.

That’s a heavy list. Were they left out because of time constraints? Is there gonna be a DVD with extras?

It gets really confusing for the viewer if there’s more than X amount of people to keep track of, and I didn’t want someone to only have one quote in the film, unless there was a reason, but all of those interviews were necessary to make it what it became. It made it stronger getting tons of perspectives.

Gino Iannucci contributes to the heavy list Jeremy interviewed. Photo: Brendan Burdzinski

OK. Who refused to be in it?

These are kinda funny. A bunch of skate characters, whose names I’ll leave out. Haha! Bob Colacello, who I worked with at V.F. and was tight with Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd, Zac and Lucien from Lucien which is a downtown restaurant… Lucien actually passed away six months after we almost interviewed him. We showed up to do the interview, then once he was mic’d up he decided not to do it. There were a few others like that who flaked on the day. Large Professor was another one who was on the fence, but now he’s gonna help with the soundtrack, which is insane. That was thanks to Vinny Ponte.

How do you even begin with Eli and R.B.’s footage? Where did you start? Was that stuff well labelled?

It was hit or miss. I’d say the film is more split between Yuki Watanabe—who founded Club Mars—and Eli’s footage. R.B. only moved to New York in 1995, and the film is set from 1987 to ’97, so it’s really from around the time of KIDS that R.B.’s footage starts to appear frequently. It’s the Mixtape and KIDS areas of the film that have the R.B. footage.

The cataloguing was actually mellow, I had a team of a few people helping with it. Khyber Jones is an amazing assistant editor who helped a lot with the quality control and the labelling of the archive, and was on nearly every shoot we did. It really wouldn’t have been possible without him. The original labelling wasn’t as good as I’d have liked, but I can’t really say anything because my labelling on my MiniDV tapes was always horrible.

Harold Hunter’s brother Ron breaks out a photo album for the documentary. Photo: Jeremy Elkin

I never knew R.B. wasn’t from New York.

He’s from Texas, I believe. He moved to New York in ’95 to go to film school and got a dorm room near Astor Place. But yeah, R.B. had tons of tapes but they weren’t as mind blowing as Eli’s or Yuki’s because he wasn’t really filming anything other than skate tricks— Eli had mad Stretch and Bobbito tapes and club footage, and R.B.’s skate footage for that era is so good, though, as everyone knows. Each filmer has their strengths/interests.

Alright, so you’ve got all this footage, from the people who shot it, and it’s up to you to arrange it into a very important documentary that a lot of people are going to want to see. Were you nervous about making sure the right stuff went in, in the eyes of the people who were there at the time?

I’ve known R.B. for awhile, and Eli knew my Vanity Fair projects, so I thought I’d be O.K., you know? I had their intentions in mind when I was making it. The first three months of going through R.B. and Eli’s stuff, while getting the interviews, was super fun. It was a really exciting time, we were like little kids getting inspired by these old tapes and all the history.

The hardest part of making it was convincing the interview subjects to be in it. It was hard convincing someone like Clayton Patterson, especially. It was hard at first when I didn’t really know what the movie was fully about, it was more just, ‘Let’s talk about back then’. It changed, as any documentary does. It morphs as you shape it.

What about somebody like Rosario Dawson? She’s vital to the story but she’s a household name now.

Rosario was easy because she’s friends with Eli. Kid Capri was a lucky one to get. I made a project for the Brooklyn Museum on JR, the French artist, which was very organic… We interviewed 1,200 New Yorkers off the street from different boroughs. That was one of the other things I was creating while I was in production on the doc.

Jeremy Elkin on the streets with JR. Photo: Khyber Jones

So me and Khyber would be out in the street filming for JR for the Brooklyn Museum, but we’d be way up in the Bronx, which is obviously where hip-hop was born. I would pull someone aside if they mentioned hip-hop in their JR interview… There was this one dude, I asked him how he wanted to be credited, and he’s like, “They call me The Bronx Blesser”. After the interview I told him about the film I was making and asked if he might be able to help procure some interviews, and it was a little sketchy because I didn’t want JR to know that I was doing that at the time.

JR Brooklyn Museum posters on the New York Subway. Photo: Scott Furkay

So The Bronx Blesser takes me up to the next corner, where there’s this barber shop where the dude cuts Fat Joe’s hair every Monday, and all these other rappers’ hair. Or every Monday and Thursday. Something ridiculous. Right away I was thinking of who was born and raised right around there and I immediately thought of Kid Capri. I asked if they knew Kid Capri, and they were like, “Kid?! Kid owes me a favour. Lemme call his manager”. And then it was, “Right, you gotta be at Kid’s house tomorrow night”.

So The Bronx Blesser takes me up to the next corner, where there’s this barber shop where the dude cuts Fat Joe’s hair every Monday

Hell yes.

We got in Khyber’s car and drove to his hood in Jersey. Pulled up to Kid Capri’s basement studio where we ended up waiting for him for like an hour in this smoke-filled studio with all the Grammys, plaques and instruments everywhere.

I thought you were being humble when you said how lucky you’d got sometimes, but that’s some amazing luck there.

The serendipity is there, but if you think about that Kid Capri incident… I was already shooting the JR doc for Brooklyn Museum which was in itself kind of luck, but then asking The Bronx Blesser how he could potentially help, and having the thought of saying Kid Capri… If I hadn’t done the research or didn’t know the story, I probably wouldn’t have gotten that interview.

There was also the matter of coming up with the interview in just a few hours, and being sure we got enough out of him to contribute to the movie.

How do you even make something like this? I mean, from thinking of it to getting it done… How does a person do that?

I guess it wasn’t really that hard. Haha! It’s just a lot of work. It’s like, ‘Alright then, I’m gonna be doing this for a couple of years’. The hardest part was figuring out how to get people to agree to do the interviews. Jeff Pang was through Eli, Eli was through Michael Cohen at Shut originally, all this lineage, they’re all connected. Pang got us to Kalis, who recently sent the film to Virgil Abloh, and Virgil loved it. There are some crazy connections in skateboarding because its roots are so cultured.

Connecting with Jeff Pang for All The Streets Are Silent. Photo: Jeremy Elkin

There are a lot of people doing the right shit.

Yeah. And it’s about asking the right questions and being ready to work an insane amount of hours. I should say that when I make a project like this movie, I put it before everyday life things like holidays or family time or a dinner or seeing friends. Missing meetings with clients to go interview someone an hour away.. It’s a priority. It’s not going to be successful otherwise. I learned that the hard way… The reason my early skate videos were trash.

From that to a feature-length documentary movie.

The connective tissue and the story are thanks to Vanity Fair. Without having Dana from Vanity Fair to help produce the story and help with the narrative, I would not have been able to make this the way I wanted it.

Stay tuned for All The Streets Are Silent which will be released in 2021

You’re 33 and you’ve hired your old boss from Vanity Fair to work for you.

We work together, and he’s a terrific producer.

When are people going to be able to see the movie?

We’re actively trying to get finishing funds in order to release it digitally during the first half of 2021. Primarily to cover the samples, pay the labels and any other music-related fees. Large Professor has been coming by weekly. It’s such an honour to work with him these days. But yeah, thanks to everyone who’s helped me along the way. Hopefully it’ll be out in March 2021.

Thanks to Jeremy for taking the time out of his busy schedule for this interview. Find out more about Jeremy at Elkin Editions. Make sure you follow @allthestreetsaresilent to keep up to speed about the film. Trust us you need to see this one!

Jeremy has made some T-Shirts in collaboration with Yuki Watanabe dedicated to his infamous nightclub Mars (1989-1992), a pivotal location in the documentary. If you DM @jeremyelkin he is down to ship these internationally.

Previous interviews by Neil Macdonald (@scienceveruslife): Steve Kane / Pete Thompson / Tobin Yelland / Carl Shipman / Corey Duffel / Eli Morgan Gesner / Jeff Pang