Words by Farran Golding. Portrait by Zander Taketomo. Stills from Verso by Justin Albert.

There isn’t another skateboarder who has bookended the last decade with their presence in the way Mark Suciu has. In 2011, he pioneered the standalone video part with Cross Continental and, in 2019’s final stretch, he redefined the medium with Verso.

The shift from full-length videos to standalones is one of, if not the, most duly noted aspects of contemporary skateboarding. If we take the Quartersnacks Readers Survey as a voice of authority, we can see that the earliest adopters of the standalone remain some of the most influential, namely: Mark’s Cross Continental, Dylan Rieder’s Gravis section (2010) and Habitat’s Austyn Unlimited (2012). Arguably, standalones didn’t become ubiquitous until 2014 so in retrospect those case studies feel like predecessors as much as instigators of the format. With distinctive aesthetics curated across an intro, body and credits structure, perhaps their initial appeal stemmed from embracing the characteristics of full-length videos at a time when the full-length’s relevance was unclear. Familiar yet new, longform in production but short in length; these parts were welcome anomalies at the dawn of the decade. Now, they’re worlds away from the disposable advertisements or footage dumps which standalone parts have mostly become.

Despite the heavy anticipation and resulting fanfare, it was inevitable Verso would be at the mercy of a digital shelf life which didn’t exist when Mark’s career-making Cross Continental appeared. With that in mind, Mark’s indifference to the ephemeral nature of his efforts is surprising, to say the least.

“If you’re worried about a video getting lost then you’re probably not focusing enough on what you’re doing next,” Mark says, when asked if he was daunted at the prospect of Verso disappearing into the endless media stream. He accepts that videos do get lost nowadays but because they’re so widely seen, first, he still feels acknowledged in his output. However, he wasn’t always this confident. After Cross Continental, Mark didn’t know where to go next with skateboarding, so he took a pause. “That was a stupid thing to do because it made me totally demoralised,” he says. “‘How do I top this?” “Do people care?” “What does it mean to be acknowledged as this type of skater?”” It’s hard to keep a straight face as these doubts are reeled off. Mark’s impact since Cross Continental goes without saying. Although, now it’s obvious why he’s constantly moving forward. “I was looking too much on the outside, you know?”

Mark speaks with a sense of candid self-awareness and self-assurance which, maybe, could be mistaken for arrogance, if you were inclined to take it that way. His articulate tone gives diplomacy to his answers which, as lengthy as they can be, always return to the original subject with a well-reasoned conclusion. “Now Verso is out I’ve accomplished what I wanted to do. I’m older than I was when I started filming it, so now I have to do something new.”

Humble Origins

If I’ve got my facts straight, your connection to Habitat came about through Josh Kalis sending you Alien Workshop boards. How did you and Josh get in touch in the first place?

Yep, that’s true. I had quit riding for Powell when they offered to turn me am. I wanted to keep my options open, I was 16 and I really wanted to ride for Alien Workshop. I was skating in L.A. a bunch and word got out that I was trying to get on Alien. It was probably thanks to PJ Ladd. I don’t know for sure, but PJ shouted me out on The Berrics. Kalis definitely has an ear to the streets so he probably saw some of my footage too and thought, “Oh, this kid is trying to ride for the Workshop? Let’s reach out to him.” It was Kalis hooking me up and not the team manager sending me boards, I don’t think he shared Kalis’ hype for me, but Brennan Conroy, the Habitat team manager, he was stoked so he was like, “If you guys aren’t doing anything with this kid then give him to us.”

What springs to mind about your early Habitat trips and being on the road filming for Origin?

I wouldn’t call it being “on the road” because I wasn’t really filming for the video with them. Sometimes the people who skated together would go out filming together. It was fun hanging out with Stefan [Janoski]. I was very green. I knew I was green and I was okay with it so I was comfortable just listening and having people tell me what to do, basically, [laughs]. I remember Stefan telling me, “Maybe you’re just not a hat guy.” That was the day I back tail’d the kinked rail at S.F. State. Brennan had tried to get Stefan to do that and Stefan was there for it, I believe. Stefan gave me his blessing, I did the trick, then he told me I should never wear a hat again and I basically kept to it. I wear beanies now and then but I took the lesson, [laughs].

Joe Castrucci is an amazing designer, Danny Garcia is a musician, Silas Baxter-Neal is into the outdoors and he’s a family man… Do you think being surrounded by older peers with other things going on inspired you to find your own focus separate to skateboarding?

If it’s true that they influenced me in that way, it was unconscious. It was a very conscious decision to try and invest myself in other things and what I invested myself in was very personal, and always there, so it didn’t feel like it was influenced by anybody else.

So studying was a natural progression for you?

Yeah, and it was a natural fear too. The fear of, “Wait. I’m going to get sponsored and I’m going to skate for the rest of my life? What the hell else am I going to do? At 30 years old is my body going to be able to handle much more? Am I going to do something else afterwards?” Just that fear looking forward, as any skater feels if they’re honest with themselves. I don’t know, some people are less prone to that fear of the future.

Maybe they unconsciously influenced me to have the belief that… Everybody else was into other things so [Habitat] were looking for a way to market me in that same way. It’s a facet of their brand that they put things on their boards that are meaningful to the skaters rather than picking a design and running with it for the whole team. I guess I noticed that and it opened up a window for me. When I had my first colourway of a Habitat shoe they put a little ink pot and a quill on there to symbolise my writing interest.

When you’re in a video you’re happy to be in a video. You’re stoked for your friends but you’re very critical of your own part so it already feels like it’s a separate thing. You watch through it at the premiere and that’s the point where you get the most nervous so I think it’s very natural to film for a standalone part.

Cross Continental really solidified your place in skateboarding. But was it strange to put as much, if not more, effort into a solo project rather than a full-length where your footage sits cohesively alongside everyone else – like with Origin?

No. First of all, I was very used to filming parts in larger videos. I started filming for my first video part when I was 12, it came out a year later and that was a 50 minute long video. Almost every year after that I had a video part in a larger video. The first solo thing I did was probably a ‘throwaway part’ when they became popular. That was around 2009. I would constantly be on YouTube and not watching entire videos. I wonder if there was some sort of time constraint? Because I remember watching Tilt Mode, on YouTube, but watching the sections separately. So, filming for a full-length video never felt like something where you had to match other skaters. You were picked for a reason so you do your thing, go out with a filmer as you have to and then your part comes out. Obviously, when you’re in a video you’re happy to be in a video. You’re stoked for your friends but you’re very critical of your own part so it already feels like it’s a separate thing. You watch through it at the premiere and that’s the point where you get the most nervous so I think it’s very natural to film for a standalone part.

After Origin you had a part in Sabotage 3. Skating to Jay-Z’s ‘On To The Next One’ was way out of character but that juxtaposition is why it works so well. It conveys some recklessness to your skating, in contrast to how considered you usually come across. Were you into it?

I like it a lot. I wasn’t told about it. I was happy to be filming with those guys and they’re awesome people to be around. It was already a crew so I wasn’t going to tell them, “I want my footage to look like this.” They edited it really well and with their own style so I was hyped from the beginning. It’s something different, it doesn’t feel like I’m reaching because I didn’t do anything. If I tried to do that now, which I would love to do, I wouldn’t be able to do it. These days, I’m the one thinking through how I want my video parts to come out next. Everybody I work with is excited to be hands on together and the music is, to a large extent, up to me. So, if I were to choose ‘Onto The Next One’ it would just feel forced, weird and if I picked something similar it would come off so strange.

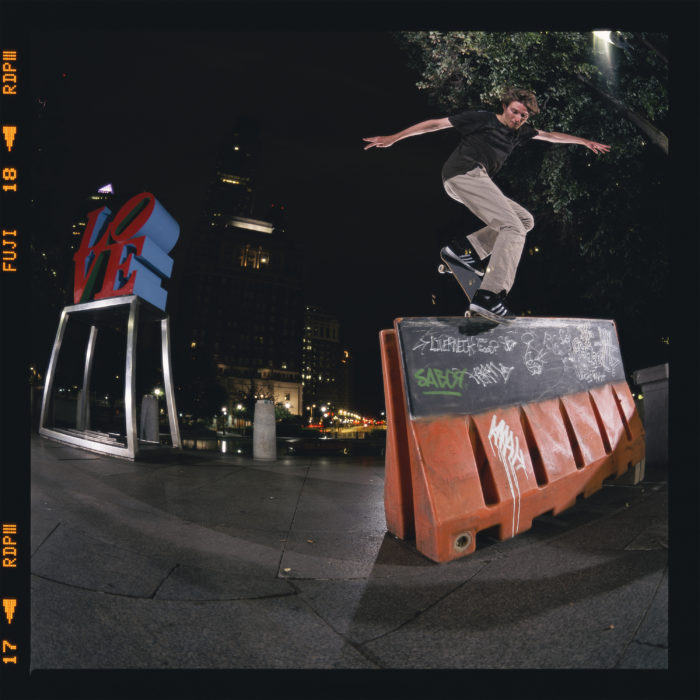

photo: Jonathan Rentschler (LOVE, 2017)

It was almost like a militaristic advantage in Love Park. You felt like you owned the place.

Temple University via John F Kennedy Plaza

Shortly after turning pro, Mark moved to Philadelphia to study literature at Temple University. Higher education isn’t out of the ordinary for skateboarders in the UK, sponsored or not, but it seems less common in the US – especially for career skaters.

Enquiring why this might be, Mark digresses that the hierarchy of US universities makes simply deciding where to study a degree daunting: “It sounds like there’s less stratification [in the UK] so maybe that leads to less stress on going to college.” Furthermore, because US skaters get sponsored earlier as a result of being closer to the centre of the skateboarding industry, “Quickly, they realise school poses a ‘threat’ to their skate career,” Marks says. He concludes that sponsorship in the UK is less demanding and therefore easier to juggle around studying (although he’s uncomfortable with generalising).

For Mark, however, being sponsored never clashed with his high school studies and the reason he didn’t immediately continue his education wasn’t out of a desire to become a professional skateboarder. Rather, he was held back by a fear that he could have got into a better institution if studying had commanded his full attention. “That’s a silly way to think,” Mark says, like he’s reprimanding his younger self. “It’s vain and you have to start trying at some point, so I’ll try now,” he recalls.

Backside nosebluntslide, Love Park. photo: Taketomo

Any fan of East Coast skating is going to have a romanticised idea of Love Park and the Philly scene. Although you’d been visiting the city for a few years before moving there, did living in Philly match your expectations?

Definitely. While Love Park was still there it was so easy for everyone to band around it and for that plaza to shape the scene. Back in the day, I think it was a little different, there were people who only skated Love Park and people who skated elsewhere. In the years I lived there, yeah, there were people who only skated at Love because they were more the chiller types but the people who were skating all the time, because there were limited hours you could go there, we’d skate everywhere else and then everybody would go to Love together.

The city is a perfect size for a skate scene. Now, living in New York there are so many little factions and cliques. In Philly there’s only so much space so everybody knew each other and skated together. It’s cool that Muni is still there, and Muni kind of still does that, but so many people have moved away from Philly now. And it’s funny, because when I left I felt exiled because I’d gone.

Brian Panebianco [Sabotage filmer] has said he doesn’t feel the same connection to Muni like he did for Love Park. You’ve had a fairly equal amount of footage at both, so did one spot resonate more than the other?

Honestly, maybe it’s an architectural thing but Love felt like it was totally yours when you were there. You could go anywhere in the park but with Muni you have to stay on the back side of the building. It’s stupid to skate right in front of the door where the security guard can see you and the plaza is laid out around the building so you can’t get to the centre of it. It was almost like a militaristic advantage in Love Park. You felt like you owned the place and the centre thing is the Love sign and you can chill so close to it.

Skating-wise, Muni is fucking amazing and it looks so cool. I like that spot a little bit better but it’s harder to skate because the ground is a little more fucked up. There are gaps in between the tiles and they pop up a lot. I was just skating there with the Habitat guys. Brian Delatorre was just pushing across the flatground and a tile popped up and he ate shit. At Love the ledges were fun if you knew how to skate them and gradually I learned how to. Mostly, when I’d cruise around, grind some ledges, skate a bunch of flat and when the fountain was empty you could skate The Levels without fear of your board going in the water; those were my favourite sessions at Love. The days where you could skate there in the daytime. But I think I like Muni more for footage and filming.

photo: Rentschler (LOVE, 2017)

There are people integral to Love’s folklore like Kalis and so on, from back in the day, then there’s the Sabotage guys, Ishod Wair and yourself who are tied to the final years of Love’s existence. Is it humbling to be a part of Love Park’s history in that way?

I haven’t given much thought to it. If it isn’t humbling, maybe it’s because I don’t see it as a big deal since Kalis and those dudes already paved the way. Also, if we’re a part of the history that’s because we were excited about the place. Everybody in the Sabotage videos; it’s not like we were doing anything, in my eyes, which was crazier than other people at the time. We were just skating well and documenting it and happened to be there at Love Park. If anything, being a part of it makes you realise it’s not that crazy. It’s just what happened.

You wrote a poignant introduction to Jonathan Rentschler’s photobook, LOVE, which reads very much like a eulogy. Was that difficult to write?

It was. I don’t know if it was difficult for the emotional content or just because everything is difficult to write [laughs]. When I accept a project of that kind I have to rationalise it in my mind. “Look, you’re a pro skater who is skating at Love all the time. You can also write and for those two things you’re being selected to write a little introduction. Whatever you write is going to be what they want. As long as you fucking proof read it and don’t come across like an idiot – you, yourself, will be proud of it.” I wasn’t stressed about it being this document that will live forever.

You’ve written other pieces about skateboarding since then. Do you approach it the same way as how you’d write a short story?

It’s kind of the same. I do think about the audience a little differently and try to be more direct than I normally would when it’s skate writing. In a short story you might leave in allusions that are connected to other issues you’re barely mentioning because you want those things to be on the outskirts of a piece. For skating, I want it all to be on the page so every ounce of it can be engaged with right then when you read it. Which doesn’t stop me from throwing in little Easter eggs, now and then, but I always make sure you can either read it unknowingly, and don’t notice the lack of meaning, or you read it knowing and you get it.

I remember when I was a kid and reading John Rattray’s writing about Paul Rodriguez warming up one morning. He sets up a board then goes to skate over a handrail. He kickflips it, tre flips it, switch kickflips it, then switch tre flips it and Rattray wrote about his feelings of utter disbelief. I’ve never been able to find that footage but it didn’t matter because it lived as its own separate event, so those are the things I like to write in. In a Free [Skate Mag] piece I wrote about figuring out how to skate this spot where you had to push and hippie jump at the same time in order to get more space. That kind of thing, a little bit of backstory, but also [exploring] a skater working out the problems of skateboarding, I feel that deserves to be in a skate mag.

What John Rattray wrote about was the feeling of watching skating but, to me, he was also saying that it’s dope when you work up to a trick, when you land tricks that are easier, and do them well, then finally end with a great trick on a spot. In Verso, I have four tricks that end with a switch tre so it’s almost like an unconscious reliving of that piece.

Getting back on track, although your familiarity with Philly’s skate scene influenced your decision to study at Temple, after you became disillusioned with skating were you frustrated that you’d let it influence your academic life?

I was really happy to be at Temple and I knew I had to step into these things slowly. It was a big life decision. Maybe I was romanticising it and wouldn’t love it so much when I gave it a try. Temple was a great place to start figuring that out. It made me feel comfortable because I knew that if I realised school is hard, and I didn’t want to do it, I could keep skating in the city that I loved. If I wanted to keep studying I would transfer somewhere that I wanted to be just for school and not for skateboarding. I wasn’t too frustrated about the whole thing but there was a kind of underlying frustration that kept me moving. I always wanted to study full-time in France and I know I would have had a better opportunity of doing that if I had gone straight into college from high school.

Nosebonk, nollie frontside 180 to switch crook, switch frontside blunt at Muni. photo: Taketomo

Novel Ideas

The development of the novel as an artform is of great interest to Mark, and something he’s drawn to out of curiosity about what it takes to write one. “On that, a larger question is, “What is a novel?” If you asked, “What’s it like to make a novel?” then you’d have to ask, “What can a novel do?” and “What is it best at doing?”” Mark says these are common questions students faced in his literature and creative writing classes as they slipped into “writing exactly as the camera sees.”

“I don’t think anybody in a contemporary novel would try to dazzle you just by the sheer description of an object. They’re not going to wax poetic about a setting sun these days whereas an author might have done that before film.” Therefore, it’s important to recognise what has already been done and the other reasons people are attracted to books.

With no exception here, many of Mark’s interviews hinge on his educated persona and love of literature. However, I can’t help but wonder if Mark feels people often pander to that aspect of his personality without having much to say? An amused chuckle follows. “I really don’t know,” Mark says. “I feel whenever people bring up the thing about books it’s mostly, “How do you feel about your image as a skater who reads?” Which is maybe closer to what people see everyday and further from wanting to know what you actually read.” On that note, here’s a taste of who Mark actually likes to read.

Virginia Woolf (English, 1882 – 1941)

Recommended reading: To The Lighthouse

“Virginia Woolf, I’ve been reading since before I went to university. There’s an element to her fiction that’s completely incomprehensible but she’s the most elegant writer,” begins Mark. “Being drawn along mainly by the prose itself into these incomprehensible moments gives you such a clear vision of the wild workings of not only the characters’ minds but also Virginia Woolf, herself. I’ve always returned to her work. I was introduced to her in high school, actually, with a short story called The Death of the Moth. She watches a moth die on a windowsill and being 17, as I was, I didn’t realise it was actually about World War 2. World War 2 looms and the [sense of] pointless, sheer facing death would have been why she wrote that story. That’s something Sebald points out.” (But more on him shortly.)

Jesse Ball (American, 1978 – present)

Recommended reading: The Way Through Doors

One of Mark’s favourite books is Tobias Wolff’s Old School, a part novel/part memoir about a narrator whose school is visited by Robert Frost, Ernest Hemmingway and Ayn Rand in the early 1960s. So, naturally, his ears perked up when it was announced that an author would be delivering a guest lecture during his second year of university. In just a couple of days before his visit, Mark became immersed in Jesse Ball’s work. “I was so in love with this guy that him walking past me in the hallway was an experience,” he laughs.

Mark attended a small lecture alongside the Masters’ students before Ball spoke to the whole university, where he was met with “these really deep questions from his own work” from Mark. “I was probably the only one who had really read his work and – just by means of a particular glance or an acknowledgement that I was really talking to him – he established a personal connection which has never left me. He’s the only contemporary author who I feel speaks to me as much as anyone I’ve ever read. There are people like W.G. Sebald and Virginia Woolf, who have written so well and I love their work, but they don’t have that immediacy.”

W.G. Sebald (German, 1944 – 2001)

Recommended reading: Austerlitz

Mark became aware of W.G. Sebald after reading an interview with Jesse Ball. He was still fascinated by, and preferred, Ball’s work but when Sebald was assigned the following year, he immediately drew parallels between the two authors through the feeling of, “Someone who is speaking directly to me, with an almost equal elegance to Virginia Woolf, and yet things are always lurking on the periphery.”

“One of his most famous books, The Rings of Saturn, is about The Holocaust but The Holocaust is never mentioned. It’s a really heavy book but super eloquent,” Mark says. Although Sebald spoke fluent English, and occasionally wrote in English, the translation of his work from German gave a “foreign sound” to his writing, with sentences populated by unusual and antiquated words. This air of peculiarity is present in both Sebald and Ball’s work, according to Mark, however their key distinction is that: “Sebald has a foreigner’s knack for the roots of words and an understanding of where words come from but not the immediate sense of context and how words work when you speak them to other people. Whereas Jesse Ball does and uses strange words, to strange effects, on purpose.”

Habitat team, 2013 with Mark pictured centre right. photo: Dan Zaslavsky

Below: Joe Castrucci. photo: Dave Chami / TransWorld Skateboarding

If it wasn’t for us recognising his greatness then nobody would because he doesn’t himself.

Honest Joe

After AVE and Jason Dill left Alien Workshop in 2013, the exodus of riders which followed felt all the more alarming in comparison to Habitat, who carried on intact (sans Austyn Gillette). Search The Horizon premiered as 2014 ticked over and was received as a true to form production which boasted an impressive curtain call from Mark, Habitat’s newest pro. Although he was now established and thankful for the opportunities he’d experienced, Mark worried skateboarding had given him a blinkered view of the world so he decided to start studying. Then, Alien Workshop and Habitat went dark due to financial issues brought on by their outside investors.

“Pretty much right when I started, in my first semester, Joe Castrucci told me about all that and said, “I won’t be able to pay you guys for a while. I totally understand if you don’t want to stay with us.”” Mark was baffled by the suggestion. “Dude, I’m going to school. I don’t need a sponsor right now, I need a board every month. Why would I leave?” He concedes that without studying keeping him occupied, he might have needed something more from a sponsor. Yet, when I bring up the team standing by Castrucci throughout that period, Mark’s admiration suggests the idea of moving on couldn’t have been more than a passing thought.

“Joe is such an amazing person because he’s totally perplexing. He’s so talented and accomplished yet he’s such an insecure person in such a loveable way. Fuck, it’s funny to say it, but I feel like I need to protect him. In the sense that if it wasn’t for us recognising his greatness then nobody would because he doesn’t himself. When he’s alone, getting coffee at the store or whatever, he’s such a meek guy,” laughs Mark, affectionately. “He can undo that sense of meekness. He can work against it, but it is there, and being with him it’s so hard to imagine the extent of what he’s done. It makes me so much happier to support that side of him.”

Verso carries a touch of Habitat’s aesthetic through the titles and motion graphics which were handled by Castrucci. Considering his role throughout Mark’s life, it’s hard to imagine that this was purely down to convenience and that Castrucci gracing the project, as subtle as his contribution is, doesn’t hold a more profound meaning. “As you put it into context, that totally rings true with me. I feel bad that it wasn’t more of a thought out thing because that is such a dear thing. I wish someone had said that to us to remind us how important it is to have him be a part of it. I’m very happy that he did something because he’s had such a defining mark on how my career looks so the fact he added to that video is only right.”

It felt awesome that the people who saw it at the premiere will feel they have been a part of the process. Then when I land it – at the time I was saying “if” – when they watch it again they’ll feel a sense of belonging, of being there to watch it happen.

It Makes Sense… On Paper

Let’s clarify this one. When Verso premiered back in July it was without the nollie heelflip to backbreaker grind at the end, right?

Yeah, that’s true.

In your Thrasher interview you spoke about how Verso was your pursuit to create something perfect. So were you uncomfortable premiering it essentially unfinished?

I wasn’t too worried because I was using the premieres as a way to get me to land the trick. I felt I needed the deadline pressure so I was still looking towards perfection and this was just a step towards it. Even though that one trick is like 1% of the part it does still feel completely incomplete without it [laughs]. After the video played I got up in front of everyone and said, “Thank you so much. The video isn’t done. We’re still trying to get this one last trick,” because, in that premiere, Justin [Albert] wanted it to end on that line but without the heelflip.

Ah, so the premiere edit had just a backside nollie into that grind.

Yeah, he wanted something that just looked smooth but I got up and said, “Check this out, this is what I’m trying to get.” I showed [an attempt at] the backbreaker trick where I get into the grind then my board pops off, flips up a little bit but I catch it and barely land back on it, then tick-tack away and do the frontside 5050. Some people got it and afterwards were like, “You’re still trying this trick? You’ve still got time? That’s insane!” To me, it felt awesome that the people who saw it at the premiere will feel they have been a part of the process. Then when I land it – at the time I was saying ‘if’ – when they watch it again they’ll feel a sense of belonging, of being there to watch it happen.

That’s a nice touch. A story for the kids.

For sure, but Justin wasn’t comfortable with it at all. He wanted to premiere it without the last section. I was happy to get up in front of people and make that little speech but he kept saying, “The second the video ends I’m going to go outside. I’m not talking to anybody,” but he stayed in there.

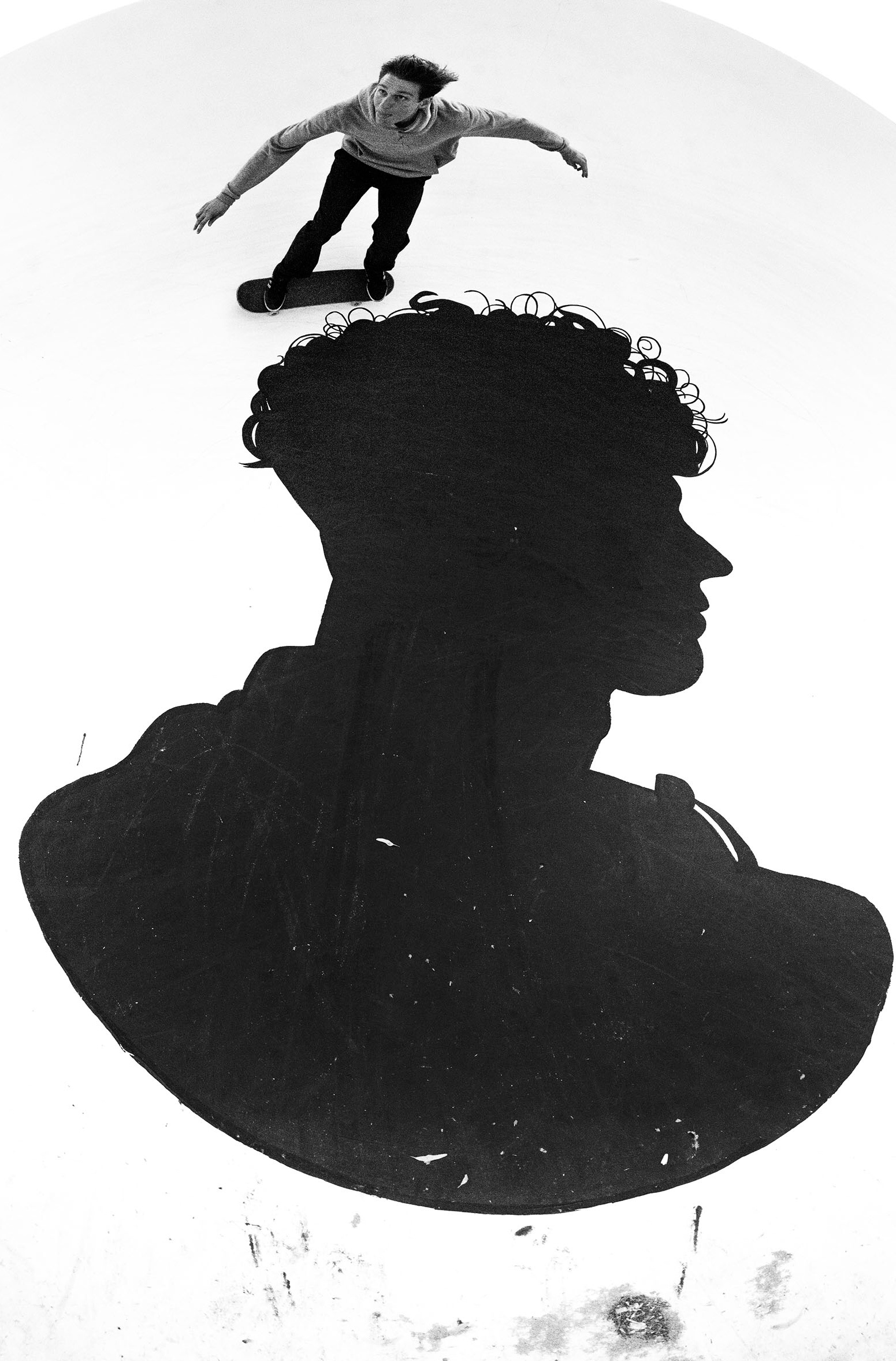

Mark and Justin. photo: Taketomo

What I was saying was, “I hate this trick. I don’t ever want to try it again. Don’t ever talk to me about it. Don’t ever act like we’re going to film it again… But we actually are going to film it so please wait for me.

What was the dynamic like between you and Justin throughout Verso?

It was great and obviously successful but we had some difficult times in that Justin didn’t quite understand what I was trying to do with the last section. It’s not that he couldn’t understand it, it’s that he felt people weren’t going to look so hard into it so he didn’t want to look so hard into it himself. He just wanted to see what he thought people would see. But the day that it came out people were already talking.

“Whoa, the tricks mirror and he does the front 5050 at end because it’s at the beginning.”

“The switch backside flip mirrors the nollie frontside flip.”

Justin talked to me that night and said, “Dude, it’s crazy, people have already explained this shit to me way better than you have,” and I’m like, “Are you fucking kidding me? I laid it out. I made a whole graph and a chart. There’s no way you couldn’t have understood this.”

Is that an exaggeration?

No, I put it down on paper and made a fucking beautiful little graph, basically. I organised everything and showed him the overall structure of it and how it works [laughs]. I think he was worried, as I was too, about ending with a conceptual thing where you end with a frontside 5050 and you’re basically taking the piss.

“Here’s my fucking great video part and here’s a little 5050.”

On top of that, he was so close to the process that he was worried I wasn’t going to get the trick. For a long time it seemed like I couldn’t do it. I had the idea two years ago, I started filming all the lines and got five or six of them in the first year on from having the idea. I started trying the last one around September 16th [last year] and I finally landed it on September 16th this year. I tried it three times in Madrid then I realised it just wasn’t the answer, it was downhill and the ledge didn’t grind that well so I thought that maybe I’d just try it somewhere else. I kind of gave up. That was back in April and I told Justin we should put it out without that final section

photo: Taketomo

The way that I told him was just out of complete frustration and dejection and I didn’t really mean it so it was hard for him to understand what I was saying. Basically, what I was saying was, “I hate this trick. I don’t ever want to try it again. Don’t ever talk to me about it. Don’t ever act like we’re going to film it again… But we actually are going to film it so please wait for me.” [Laughs].

It was a psychologically trying process for the both of us so you can imagine we had a difficult time understanding each other because we were having a hard time understanding ourselves. Then working on the edit together in the last couple of days before the first premiere was really fun. We went into it stressed and instead of saying, “We’ll figure it out when we get there.” I told him point-blank, “This shit isn’t working out the way I want it to.”

I wanted to get it all out on the table and have him be stressed and ready to go into this thing gung-ho. To an extent, that wasn’t very nice of me but it helped because when we sat down he had already done a ton of work. I just told him the parts that I wanted to look at, how I wanted things to sync up and very quickly things started working better. It was a big change and after each night we would sit, he would smoke and I would drink a beer and he would say, “It’s going well but you need to get better at asking me to change things because every time you say, “You need to change something” I feel like the world is going to end and we’re going to have to change so much. Then we do it and it isn’t so bad.”

You’re hard to work with then.

Oh yeah, for sure. I don’t think I would work that way, and I never have worked that way, with anyone I don’t know so well.

It’s a term of endearment.

It’s tough love. Even when we’re not working on something together I’ll bust Justin’s balls. I’m quick to say what isn’t working but I always remind him the reason I’m working with him is because he’s amazing at what he does and his support has been totally integral to the success of my skate career.

Switch backside noseblunt as seen in Verso and Vague Skate Mag #9, courtesy of Reece Leung

I wanted a slew of tricks that would look insane and gradually the second trick becomes easier. I wanted the initial reading to be, “Wait? What? Why?”

Citations

Any talk of ‘mirror tricks’ instantly makes Arto Saari’s iconic bench lines from Sorry spring to mind. On first glance, they’re an obvious point of reference for Verso and the change of pace with each new song, coupled with Mark’s tendency to rifle off a barrage tricks on individual spots, appears to further echo Arto.

As it turns out, Verso actually owes more of a debt to Zered Bassett. Specifically, his part in Vicious Cycle which opens with Zered hammering out 12 consecutive tricks on the same rail to the beat of ‘Gimme Some Lovin’. “I’ve heard that’s just how he would skate spots,” Mark says.

“For me, it was natural and inspired at the same time because I live really close to Pyramid Ledges, for example. I kept going back there to do more tricks because when I would land one then the option for another would open. That’s the best out-ledge I know of so when I’d learn a new trick it was really easy to say, “Well, what if I did this at Pyramid Ledges?” So, naturally, I ended up doing a lot of tricks at that spot but I wanted to curtail it in a way that was paying homage to Zered.”

Backtracking to Arto, it’s easy to overlook the true extent of his ambidexterity in Sorry. Bench lines aside, tricks are often mirrored in succession but at different spots, something which went over Mark’s head until recently. Coincidentally, he spent the morning before our interview watching a bunch of Arto’s parts as he’s been getting into skating rails. “But yeah, no Arto influence,” apparently. “The mirrored stuff wasn’t influenced by skateboarding. It was only [as far as] skaters do mirror lines. And they’re all unimaginative.”

Care to elaborate on that?

In Arto’s part, what is it, a switch front crook at the end? He’s going from left to right on the screen: half cab crook, crook 180, switch front crook. He approaches that switch front crook and, if you’re paying attention, you know he’s going to do that switch front crook because the end of the first line was a front crook. When you’re watching it there’s no disbelief, you just think, ‘switch front crook’ and then he does it. To me, that’s boring.

The other thing about mirror lines is the concept distracts from the skating itself. Skaters do something ‘easier’ because it’s ‘cooler’ when, in my mind, it’s not cooler it’s just easier. With this thing I was inspired by the idea of chiasmus and fucking with the preconception of doing the harder of tricks second. I wanted a slew of tricks that would look insane and gradually the second trick becomes easier. I wanted the initial reading to be, “Wait? What? Why?” Confusion and a recognition that this is backwards. I was looking for the people who would see the frontside 5050 and think, “Wait a second, why did he do that?” then go back and start to realise how they’re all connected. Then end by saying, “Oh, interesting.” So, it’s more than the first viewing.

Then then ender: trick, push, cut to black. PJ Ladd…

We didn’t set out to do that. I wanted the cut to be really long, to do the line and then just push because that would be the most amazing feeling.

A victory lap.

Yeah, a little victory lap [laughs]. I actually had a dream that I pushed switch – I don’t know why I would’ve been pushing switch – for two blocks and then I did a switch tre, a switch laser flip and then the PJ trick [from A Wonderful Horrible Life], the fakie bigflip full cab. I think my brain is PJ Ladd’d out from the wiring.

It wasn’t a conscious decision but of course I realise that’s one of the only precedents for that. I couldn’t do the victory lap because there’s this fucking crack right after the 5050. In the full clip I take that push but as it’s happening my board is re-routed by this crack and I never even get my foot back on my board. Then I just run away screaming.

I wasn’t going to do it again so when I sent it to Justin he said he was going to cut it mid-push and I said, “Yeah I think that’s the only way to do it.” Then I sent him the PJ push: “I’m just showing you this because everybody is going to talk about this…” It just happened that way but we were very aware that everybody would see that. I don’t know how that figures into artistic intent and all that shit but I think the fact of the matter is that is an homage to PJ even if I wanted it to be or not.

Did you ask for Billy Rohan’s blessing on the backside noseblunt at Black Hubba?

No, I didn’t. When I was 13, I was skating with him and he said, “Hey man you’re killing it. Here’s an Autumn shirt and here’s my video. Remember me when you get all famous.” I wore this shirt at all the contests I skated in because it was my lucky shirt. Then I skated an adidas demo at Tompkins, when I was like 24, right when I had just moved to New York, and he kept pronouncing my name wrong. After about half an hour I went up and said, “Yo, my last name is pronounced ‘Soo-chew’, with a ‘U’ at the end, not an ‘O’. But by the way, I skated with you when I was younger and you were real nice to me. Thanks so much for hooking me up.” He looked back at his turntables and then goes, “Oh for sure man, you French? Hell yeah.” I’m not French. The name isn’t French. Then he continued to pronounce it wrong [laughs]

I asked around a bunch of people who I considered to be the right people in New York. “What do you think? I really want see this fully dug in and to regular. That’s the way I imagine it being done at that spot.” I had a little jury. I was actually talking about it in Labor one day and some guy who I didn’t even know piped up.

“Billy Rohan? That dude is my best friend, but I don’t give a shit and I know he doesn’t either.”

It’s really a different trick too because I went to regular and he went to fakie. Whenever anybody brings it up, I just say that and they’re like, “True, it’s a different trick.” No disrespect at all because it’s so insane that he did that. It was so long ago and that spot is so difficult to skate. To go up at a nearly 45-degree angle and turn an extra 45 degrees to get into a backside noseblunt, yet not go over the entire ledge and slide through that kink is really hard so I have respect for him. I just had to do it the way I envisioned.

The different songs in Verso help keep the momentum going and also structure the video into different sections. Was there any reason behind each piece of music?

I’ve always tried to skate to a Beirut song and I kind of did in Cross Continental but that was [current Alien Workshop cinematographer] Miguel Valle’s idea. I would have said to use the whole song but Miguel just went with it. I thought it worked but, to me, that never felt like skating to a Beirut song. During Away Days we tried to get the rights for a Beirut song but, I think because we were working with a big company, Beirut didn’t want to do it even though Zach Condon [Beirut’s founder and lead musician] had skated or does skate, I think. Maybe it was also a licensing thing with his label. Even though Justin wrote a very touching letter to the band they still declined us. Finally, that was what made us go independent and not do another adidas part, for example.

I wanted to skate to the Beirut song at the beginning because I love that song, it has good energy and ‘Scenic World’ is [accompanying] the section where there are tricks from all around the world. Air and ‘Sphynx’ were Justin’s ideas and what’s funny is I had recently seen The Virgin Suicides so I was sure nobody would like that [Air] song. People mentioned that but nobody was like, “Why would you use a song from a movie?” I love it now, looking back without the insecurity, but during the time I liked it but I felt so weird about it.

‘Sphynx’ was a great choice [the French song accompanying the New York section of ‘Verso’ – ed.].

I agree. Listening to these songs before they premiered, I didn’t realise how much bass there is in ‘Sphynx’ and how little there is in the Beirut songs. I even asked Justin, “Can you turn up the bass in ‘Scenic World’?”

“Bro, those are fucking acoustic instruments. There’s no real bass.” It made for an amazing spectacle at the premieres, just being fucking blown out of the room by ‘Sphynx’

We spent a long time trying to figure out what music could go well with the verso section at the end. We knew it was going to be short and that made me think of using some sort of experimental piece of music. We were looking for things in the vein of the Mind Field section where it’s just the flashing lights or maybe a Phillip Glass piece but every time we tried those it was just a little bit too dramatic. Justin wanted to lock down a song for the premiere so I said, “Let’s just use this song from the same [Beirut] album, ‘My Family’s Role in the World Revolution’, because then we’re going in line with the whole theme of chiasmus.” That song is already short and it had the kind of sophistication I wanted. A different sound than what you normally would hear [in skate videos] but the energy is what I loved about it. I wanted something which would give us that lift, that rising tempo at the end of the project to return on a more triumphant note.

photo: Taketomo

To a degree, with ‘Verso‘, making a chiasmus and giving a whole section of skateboarding that structure, the fact that I read books and that I am this kind of person dictates how I skate and put together a video part.

Reflections

Sifting through Mark’s past coverage in preparation for this, I came across a remark about how he used to hate interviews because he felt people would make judgements about a person’s skating, swayed by article focused around them as a person.

As he’s been so vocal about the thought process behind Verso, I’m curious to know if he’s changed his opinion about the separation between ‘art and artist’? For want of a better phrase.

“I guess I have. The separation of ‘art and artist’ is a really youthful, idealistic concept; that art lives in its own realm and it doesn’t depend on the historical and personal context of whoever created it in whatever era. It’s wishful thinking that they could be separate,” Mark says, although he goes on to observe that his personality and actions on a skateboard are met with different receptions. As much as he wishes people could watch him skate without the bookish nature in mind, it’s a superficial thing to be bothered by, so he’s come to terms with it.

“I think not speaking in interviews, not telling people that I read books is cloistering myself and it’s not helpful to anybody who wants to live a complete life while being a skateboarder. That’s the superficial level but on a deeper level looking at the whole thing together, putting art and artist together… To a degree, with Verso, making a chiasmus and giving a whole section of skateboarding that structure, the fact that I read books and that I am this kind of person dictates how I skate and put together a video part. So, the link between art and artist is obviously ingrained.”

By his own admittance, Mark thinks too much about video parts. Even his Story Edit from November, which on face value is just phone footage, still had a premise. He’d heard of novelists projecting onto a screen while writing in front of an audience, “So you could see them deleting the words and all that.” Playfully, he felt this translated to clips disappearing from Instagram Stories, “And it works like this is ‘the verso of Verso’. This is the behind the scenes, this is when I was warming up at the spot or doing something silly or skating another part of it.”

Mark reconciles he “needed some recognition Verso was kind of an intellectual thing, and that it could be appreciated as that, as much as a good skate video, in order to feel like skateboarding is a comfortable place for me to be, that accepts me for who I am,” but regardless, he’s equally stoked if people just enjoy it for the skating and not the intent behind it.

“It’s gone way above my expectations and people often message me about the structure of the last lines or the reference to PJ Ladd and I respond back, sometimes. Most of the time, it’s just like, “You thought about it and I appreciate that,” but I feel like people think I need some sort of engagement from everyone, you know? Like, “Hey, I got it! This is me getting it, isn’t it?” If it stimulated you in that way then I’m psyched but my first priority is the skating so not too much is lost if nobody gets it.”

When prompted, he’s hesitant to speculate about the lasting influence Verso may have. Although one thing’s for sure: he’s over concept parts. Ultimately for Mark, people skating how they’re naturally inspired to, and pushing themselves based on individual taste, is more interesting than having a certain theme restrict their potential, in a sense. “I was just focused on making what I wanted to make so maybe that’s a better answer,” he says earnestly. “I’d like to see people trust what they’re about and doing something they believe in.”

Afterword: For Ben

photo: Reece Leung

This interview found Mark and I speaking to each other about a day or so after the launch of The Ben Raemers Foundation back in October. Before we got off the phone, I asked Mark if he’d like to share a story about Ben to close this piece out with. Mark felt that it was also important to highlight Justin Albert’s connection to Ben, so here’s what he had to say:

“Justin lived with Ben in 2010/11, somewhere along the road when Justin was still in college and Ben was first coming out to the US to skate for enjoi. I think it was his first apartment there. Justin’s in that video that éS made when Ben is painting, talking about public art and long drives with sugar in your mouth.

“Justin lived with Ben in 2010/11, somewhere along the road when Justin was still in college and Ben was first coming out to the US to skate for enjoi. I think it was his first apartment there. Justin’s in that video that éS made when Ben is painting, talking about public art and long drives with sugar in your mouth.

“Justin was so close to Ben that with Verso coming out within a couple of months of his passing, he knew he needed to make some sort of memorial for him. I was close to Ben as well so I was happy he suggested that and felt what he did was beautiful, succinct and did justice in a small way.

“When we went out for Ben’s funeral, I was skating with Jake Harris and Casper Brooker while they were filming for Trust Fall, just the last couple of sessions. I was there for Street League too and [at Street League] I skated in a shirt I made with a photograph I had taken of Ben because, skating in London, I knew I had to do that. I saw Casper doing a similar thing, he wore a Ben shirt when he was trying to film his [Trust Fall] ender.

“I was also trying to film my Verso ender at the time and I thought, “I still have this shirt, maybe I’ll wear it,” but it never clicked as something I had to do. On the days that I would wear it, I felt a little more inspired to try harder, to keep going, to push through. Then near the end it clicked that with the chiasmus, with the ABBA structure, using the Beirut songs at the bookends of the video; I had to wear the Ben shirt in order close out with Ben where we begin with Ben. Even though it’s a small little graphic on the shirt and 99.9% of people wouldn’t see that, or wouldn’t even know what it is, I just had to do it for myself.

“That was right before the end when it really seemed like it wasn’t going to happen, but I had to make it happen because it was the last day of filming. The night before it occurred to me that it isn’t just that I should wear that shirt, it was that this whole thing made sense to start and end with Ben. I jumped out of bed, made sure the shirt was clean and hung it up to wear.

“I went to do the line and I did it in five tries because I was so sure that I was going to do it that day. There was no doubt in my mind that it just had to be, you know? So, he was there with me that day and he’s totally ingrained into the spirit of the project even if you only see him at the beginning.”