Intro and interview by Farran Golding. Portrait by Sarah Anderson. Stills courtesy of Bobshirt.

Although better known for the Snuff logo-led interview series where skateboarders are reunited with iconic boards, shoes, VHS tapes and other objects related to their careers; Bobshirt began as a “clunky, low tech website about skateboarding in the ‘90s” ran by a friendly guy named Tim Anderson.

Back when dial-up encompassed half of the world’s internet access, Tim began catalogueing parts from ‘90s classics like Trilogy, 20 Shot Sequence and Tim and Henry’s Pack of Lies to his Bobshirt website simply because he felt anyone should be able to the enjoy them (regardless of owning a VHS player). Long before Thrasher held their monopoly on video part releases, Bobshirt was home to the most curated selection of online skateboarding media.

Around the beginning of Bobshirt, Tim also began searching for his first ever skateboard. Over the following years he accumulated a vast and diverse collection of decks from any company you’d care to own a wall hanger from. Then, about ten years after uploading Snuff parts to Bobshirt, Tim found himself interviewing Gino Iannucci in preparation for Deckaid, a skateboarding-focused charity helmed by Tim’s wife, Sarah, which established the format of his sporadic video interviews.

Thanks to Tim’s amazing skateboard collection, his Bobshirt interviews always unearth new knowledge and charming anecdotes which would be otherwise unobtainable, meanwhile, he and Sarah have continually put his archive to further use and raised thousands of dollars for great causes with Deckaid.

Speaking to Tim, it’s obvious he’s slightly bashful about the extent of his skateboard collection. But considering what his love for a personal “golden era” has led to, I think that feeling is pretty misplaced.

What can you remember about the skate scene you grew up with in Long Island?

Well, actually, I grew up in a suburb outside of Boston. From what I remember, Jahmal Williams was the local pro. I wasn’t friends with him, but he was the first pro I saw where I thought, “Oh, that guy!”

It was Boston for a bunch of years but then I moved to New York in 1998. I was 19, so [my skate scene] was like The Banks, The Seaport and just Long Island skaters who I would see around. I saw Frank Gerwer every once in a while, and very rarely we would see Gino Iannucci, but he was mostly in California by then. We got to see Anthony Pappalardo come up, he was part of our little crew.

I think the years between 18 and being in your mid-20s are your most formative, so how did travelling into Manhattan, during that era of New York, shape what skateboarding was to you?

Nothing against Boston but with the skateboarding scene in New York; it seemed like everybody was good. The scene was so alive and there were so many crews of kids skating. In hindsight, there probably wasn’t that many people but back then it seemed like everybody was pushing themselves. You’d go to The Banks and some no-name kid would be doing switch 360 flips around the planter. It was just a whole new world and I totally fell in love with it.

How’d you get to know Anthony Pappalardo?

Just through a mutual friend. We used to skate this spot out on Long Island called Home Depot a lot and Anthony just started coming around. He was younger than us, a good five years younger, but it seemed like the young good kids ended up rolling with the older guys and we would take them into the city and stuff like that. My friend Steve Fletch started bringing him around.

“Who’s this little kid?”

“Don’t worry, he rips.”

We all saw it really quickly and thought, “This kid is something.” It was insane. He was the first kid that was doing switch backside tailslide shove-its and it wasn’t a big deal. “Oh, you’ve just got to think about it like this…” He was just so good. Then he moved to Philly and we would visit him every once in a while. It was definitely a good move for him because, at that time, Philly was the place to be.

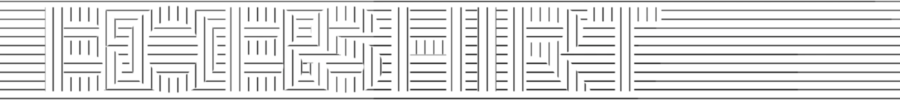

16 year-old Anthony Pappalardo noseblunts in New York. Backside, Long Island, and frontside at The Crooked benches in Manhattan. Photos courtesy of Tim.

So, I take it you guys were pretty close? I know you shot a few photos of him which ran in Alien Workshop’s short-lived zine. ‘The Blacklist’, was it?

Yeah, The Blacklist. We were pretty close. We skated together a lot. We would see him in the city, we would skate with him on Long Island all the time. He didn’t even have a license yet, so we’d end up picking him up, but he went pretty quickly. He got a checkout in TransWorld, which Reda shot, then all of a sudden he’s on the Workshop and then he’s in Philly, [laughs]. I remember going down to visit him in Philly and he said, “Yeah just meet me Love,” and Josh Kalis was there. Everybody was there and I’m like, “Holy shit! This is awesome.”

Can you remember the first time you saw Gino out in the wild?

Yeah, he showed up at Home Depot one night. We would skate there all the time and it was late, it was probably 11 o’clock at night and he hopped out of a car. “That’s the guy!” He had this red Polo fleece on and he just started ripping right away. It was so random. When he came back to Long Island back in those days, he wouldn’t skate that much, I think. He would if he was getting a photo or filming something, but he wouldn’t be casually skating.

photo: Sarah Anderson

That Jason Dill, 101, Winnie the Pooh deck? I got that off Craigslist from some girl who collects Winnie the Pooh stuff.

Let’s get into the board collecting side of things. I know you started around 2005 while searching for your first board, a Chris Pastras World Industries. This is still early days for the internet, or as we know it now, anyway, and I can’t imagine the eBay listings for ‘90s boards were all that fruitful.

Yeah. It was hard. There was one forum called Skull and Bones and that’s where everybody went because nobody was on Facebook, I don’t even know if Facebook existed. We would all go to that forum to trade and sell but it wasn’t even ‘90s based. The guys on there were collecting ‘80s stuff and there was a handful of us that were collecting early ‘90s World boards and stuff like that. You’d scour eBay but…

Everybody is connected now and it’s easier. Well, it’s not easier to get a board but it’s pretty easy to track a board down. Back then, it could have been anywhere. You’re picking up the phone and making phone calls, you’re calling old skate shops and asking if they have any old stock. Sometimes it would work. You’d even be checking Craigslist. That Jason Dill, 101, Winnie the Pooh deck? I got that off Craigslist from some girl who collects Winnie the Pooh stuff. [Laughs.] Everyone’s much more connected now, which is great, but it was a little more challenging back then. But it was fun too, the hunt is kind of fun.

Everybody is connected now and it’s easier. Well, it’s not easier to get a board but it’s pretty easy to track a board down. Back then, it could have been anywhere. You’re picking up the phone and making phone calls, you’re calling old skate shops and asking if they have any old stock. Sometimes it would work. You’d even be checking Craigslist. That Jason Dill, 101, Winnie the Pooh deck? I got that off Craigslist from some girl who collects Winnie the Pooh stuff. [Laughs.] Everyone’s much more connected now, which is great, but it was a little more challenging back then. But it was fun too, the hunt is kind of fun.

It took me a really long time to find that [Chris Patras] board but in the meantime I started collecting Keenan Milton boards and stuff like that. It slowly evolved. I’d find other boards I had when I was a kid, or boards my friends skated and it got a little out of control, [laughs]. As it does. I would buy a bunch, I’d sell some and obviously I have my regrets but you can’t keep them all. Sometimes, in order to buy something, you’ve got to free up some cash, you’ve got to sell something to buy something else. That’s just the name of the game.

What was your day job back then and what’s your current life outside of Bobshirt? How did you, and how do you, currently fund your habit? [Laughs].

I don’t really buy many boards anymore. It’s been a while, actually, but there’s always something out there. I work in the film industry doing lighting and rigging. It’s a good job and pays pretty well but the hours suck. It’s a minimum of 12 hours on set, per day. I started that when I was 21 or 22, right out of college, and I still do that.

I wanted to be a camera man on film sets, basically. You start with lighting and you work your way up to being a camera man, which I never did, I just got stuck being a lighting guy, [laughs]. But the money is good so it’s hard to make that jump. You have to make a lot of sacrifices to be the camera man; you’ve got to work for not a lot of money, for a long time. I just stayed doing the electrics stuff.

At first, I did a lot of music videos and commercials. I don’t do movies anymore, I did back in the day. My first music video was Sean Paul, the rapper, and it was awful, [laughs]. It was these girls dancing at a bar, a typical hip-hop video from the ‘90s, but the song was huge. I would hear it all the time. It was ‘Deport Them’. A club hit for sure.

I know the original Eastern Exposure was a white whale for you until recently, but what board is still eluding you to this day?

It’s a 101 board, a Gino Iannucci, and he’s standing up against a wall and Natas [Kaupas] did a huge spray paint piece. Gino is standing there, and he’s spray-painted into the piece, his clothes are spray painted and everything. It’s a slick bottom. It’s really cool. I think it came out in 1994, or something like that. I know where there are two but the guys that have them aren’t getting rid of them.

Then there’s a piece of art that I’ve been after. It’s a Keenan Milton Blind board by Sean Cliver, it’s Keenan’s first deck on Blind. He’s in the garbage with the World Trade Centre in the background. I have the deck, but I’d love to get the original artwork too. Which, I also know where it is but, again, the guy isn’t moving it. But that’s how it is, [laughs].

‘A piss-yellow XXL bob shirt’ – Tim’s website circa 2006

Before Bobshirt became Bobshirt in 2006, it was guymariano.com. Can you explain the name and its link to World Industries?

I’d meet kids who had never seen the 101 Snuff video but there was no YouTube. So, I thought, “I’m going to figure out a way to get these clips online.” I made that website and named it after Guy Mariano because he was gone, and I thought he’d never be back. Then he came back and I was like, “Shit. I’ve got to change the name,” because people were emailing me saying, “Guy, I love your site!” It felt like false advertising.

I couldn’t come up with a good name and I kind of rushed it. So, ‘Bobshirt’, I wanted it to be something totally random which most people wouldn’t get. Bobshirt was on the tag of the old World Industries shirts and they were the best shirts. 101 and all the early classic World stuff was printed on ‘bob shirt’ shirts. It’s a stupid name and I kind of regret it, because it’s a goofy name in a way, but I named it that just because I wanted to change it real quick and dump that Guy Mariano name because I felt kind of bad having it, [laughs].

Via Wayback Machine, I found an early snapshot of the Bobshirt site and your page full of thumbnails for videos, which is now labelled ‘hi8’. Having that many skateboarding videos in one place would have been totally unique at the time, or curating a selection would have been, anyway.

That’s what I wanted, just to put all of my favourite clips online. It was up for a month and it was pretty quiet. I don’t know how the word got out but I got an email from my internet service provider saying I was way over my data allowance and that I had to update my plan. It was slower to figure things out. You could log-in and see where traffic was coming from, and I did that and saw that, “Oh okay, I guess people do actually want to see this stuff.” I remember realising I had to cough up a little more money to keep this thing going, [laughs].

It is what it is now and you can’t stop it. It’s like a runaway train. Some companies still put out full-lengths and I think that’s fantastic. There’s room for both, fortunately.

Do you think the instant access of today makes archiving any less special or just allows for more of it?

You know, I’m guilty of it. Not guilty, but I’m on Instagram looking at the latest clips and I love it. Everybody is their own little brand now. Every guy is going to put their own one-minute video out. It is faster and things expire much quicker. You know, we would hold onto a full-length video for a year and watch the parts over and over again. Now, you watch it once or twice and it’s gone. But I don’t mind, it is what it is now and you can’t stop it. It’s like a runaway train. Some companies still put out full-lengths and I think that’s fantastic. There’s room for both, fortunately.

In the early days of Bobshirt, you published a few interviews with Ronnie Bertino, Jacob Rosenberg, Drake Jones and Henry Sanchez. How come you didn’t do any more of those?

I’m kind of introverted… Well, not really introverted but those were email interviews so there weren’t any follow up questions. I wasn’t the guy to say, “Hey, let’s do a phone interview.” I felt weird about it at the time and I thought it would be easier for the recipient to email them a bunch of questions and say, “Take your time.” In hindsight, I don’t think email is a good kind of interview, you just get bad answers. I stopped doing those when Eric Swisher started doing the Chrome Ball interviews. I was like, “He’s doing a much better job. I’m not going to go up against this guy,” [laughs]. He’s the best. Chrome Ball is such a gift to skateboarding media. I use it all the time if I need a reference image for an interview I’ve shot. He’s got so much good stuff up there and it’s so well catalogued so shout out to Eric, [laughs].

Deckaid New York City, The Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn ( 2015). photos: Jersey Dave

As we’re taking this in chronological order I think it’s important to talk about your wife, Sarah, as it was her idea to start the Deckaid charity shows which lead you to Gino for the first Bobshirt video piece. Does Sarah skate herself?

She skated when she was a kid, but she stopped. She saw my pile of skateboards and said we should do something with them, some kind of charity work because she thought other people would like to see those boards. I said, “That sounds like a disaster,” [laughs]. The logistics of it and taking all this stuff out, it’s kind of embarrassing. She was like, “I think it’ll be good, people will show up,” so it was down to her.

The first time you exhibited your boards was as a fundraiser for a local skatepark in 2013. How did that concept evolve into establishing Deckaid and hosting the first show a couple of years later?

It was a great success and there were some skaters there, because they wanted to support the skatepark, but regular people came out and loved it too. Because [the skatepark fundraiser] was at a place called NYAC, which is upstate a little bit, Sarah thought we should try it in Brooklyn, at a real gallery and we could make some prints and give all the money to Skateistan, which is a great project. So, we did that show in Brooklyn, raised like $6,000 for Skateistan and Sarah thought we should keep going. We worked with Skateistan for the Philadelphia show too but then Sarah wanted to change the model a little bit to benefit a charity local to whatever city we’re in, which is a great idea. It always benefits youth and youth in need within a local community and we don’t make any money off of it.

Deckaid Philadelphia, Exit Skate Shop (2015). photo: Jersey Dave

Did it take much to convince the curators of a contemporary art space to host a skateboarding exhibition or did they instantly see some merit in it?

‘20 Years of Chocolate’ was in town, about a year and a half earlier, at the same gallery so they were already kind of broken in with skateboarding. When Sarah approached them, the guy loved the idea so we rode Chocolate’s coattails a bit with that one, [laughs]. We’ve had to convince some gallery owners that it’s going to be okay, they always think the worst if they don’t skate or they’re not really into skateboarding. It takes a little arm-twisting sometimes.

What did you and Sarah learn from the first Deckaid show which influenced how you approached them from then on?

The takeaway was: for the first show it was all my stuff and we both said we shouldn’t do that again, it would be better to get other collectors on board. It would make it more dynamic. It would get more people excited. I liked the idea of having other collectors on board because it’s fun to share that experience. They can hang their collection and there aren’t a lot of outlets to do that these days, surprisingly. So, mainly, it was to get other collectors on board from the local scene and give them the opportunity to show their stuff which makes the show different every single time.

Deckaid New Jersey, The Proto Gallery, Hoboken (2018) / Below: Gino and Sarah Anderson (2015)

Then the idea to shoot portraits of skaters holding their classic pro models – again, that was Sarah too. How difficult was it to track down Gino, Scott Johnson, Bobby Puleo, and so on, to shoot those?

Sarah’s from Long Island so she had mutual friends with Gino. With Long Island, everyone is kind of connected from the ‘90s. It was pretty easy to track down Gino. She was like, “We’re going to shoot this portrait with Gino,” and I thought, “I should try to ask him some questions about his boards while we’re there.”

Sarah’s from Long Island so she had mutual friends with Gino. With Long Island, everyone is kind of connected from the ‘90s. It was pretty easy to track down Gino. She was like, “We’re going to shoot this portrait with Gino,” and I thought, “I should try to ask him some questions about his boards while we’re there.”

“Okay, if that’s what you want to do…” And that’s kind of how it went.

We shot one with Gino and it was kind of a disaster. It was okay but the sound wasn’t good and, I don’t know… He let us reshoot one a couple of years later which worked out better.

How nervous were you about interviewing Gino?

I was buggin’. [Laughs.] “I’m going to hand him a bunch of boards… and have him talk about it? And I’m going bring a shoe.”

I remember when I said that, Sarah was like, “I don’t know if you should bring a shoe to talk about.” [laughs].

“But it’s kind of important. It’s about the guy’s history.”

“Alright, whatever you want to do…”

I don’t really need to prepare to interview Gino, because I’m a fan of his, but I totally overthought everything and it still didn’t really work out that well.

“Keenan used to do back lips right there!” – The first Bobshirt interview with Gino (2015)

Did the response to Gino’s interview encourage you to keep going or was it because the opportunity was there and it would have been silly to not take it?

I just think it’s fun. I like to nerd out on this stuff and it’s funny to hand over physical objects from somebody’s career in skateboarding and to see their reaction on camera. I like it, so I just thought that I’m going to keep doing this for as long as I can and as long as I want to. It’s slowed down a lot recently but it’s hard to get guys to jump in front of your camera and talk about themselves for who-knows-how-long.

What did you learn from that experience which you took forward? And how did you find interviewing Gino the second time around?

Get a tripod, [laughs]. Bring more stuff, and I can always cut it out, edit it a lot quicker with more jump cuts. The attention spans these days are low, and that’s okay, but I still like long content.

I was nervous, but just because we were doing it again.

“Let’s talk about the backside heelflip at EMB.”

“I don’t want to talk about that anymore.”

But I still made him, [laughs]. I brought a board and he was like, “I don’t want to talk about that board.” He was a little more comfortable and I was a little more comfortable. That was a fun one. I brought more shoes. Now I just push it and hopefully they keep talking, [laughs].

Round 2 with Gino (2016)

Gino says he doesn’t have his 101 Gravediggas board. Is that what lead to reproducing that graphic as a print for Deckaid?

Kind of. I always loved that board too and, honestly, it was an easy one to reproduce. It’s hard to find all the art. The guy who did the original art gave us his blessing to do that. It’s a cool graphic, it didn’t really make sense because it was for a Boston show and we had Gino, and Gino is New York, you know? We also did something with PJ Ladd for that show, so we had the local tie-in, we always try to get a local tie-in.

Did the Bobshirt/Snuff logo come into play just because the 101 connection was there from the start?

I always liked the Snuff video and, I’m not good at graphic design, but I do everything myself and it was an easy one to recreate. It’s not in your face. Some people don’t even see that it says ‘Bobshirt’ and that’s okay, I’m not trying to shove it down anybody’s throat. I just ran with it and I’ve had friends make other stuff. Someone did a Benetton bite, I liked that, but I just stick with the Snuff one and it works.

What’s your process for editing the interviews? Is the skate footage always ripped from your VHS copies?

Sometimes it is, sometimes I don’t have the time and I’ve got to get it off of YouTube if the quality is good enough. Lately, it’s been about 75% my stuff and 25% YouTube if I don’t have it. Editing is very time consuming and I have my regular job and my family life. That Rodney Torres one took almost two months to edit. Granted, I’m doing an hour here and an hour there after work but every time somebody is referenced, I try to find a clip of that of person. I like to fill them up with a lot of reference pictures and videos so it’s not just a talking head for an hour, basically.

‘Photosynthesis’ via Bobshirt:

Anthony Pappalardo (2015), Brian Wenning (2016), William Strobeck and Josh Kalis (2017)

The naturally nostalgic aspect of your interview format always makes for an earnest conversation. Sometimes, the interviewees have a really noticeable emotional reaction to the objects you present them with too. Have there been any instances where you’ve been really taken aback by the reaction to something you’ve pulled out?

Not really, that’s just the reaction you hope for because a lot of guys didn’t hold on to stuff. It’s cool, I love it and I’m the wierdo that has all this stuff. I’ve given some of it away to guys after the interviews, when they say they didn’t have it or mention it was special. You’re like, “Alright, here you go…” [laughs].

Is there ever a feeling of, “This is your board and you should have this, not me,” if that makes sense?

Sometimes it does, yeah. It’s a mixed bag. Part of me thinks, “Well, I can justify owning it because we’re putting it in the Deckaid shows and putting it to work for charity,” – which isn’t always the case, honestly, but I do feel like that sometimes. All the guys, usually, if they have it then they have it – but if they don’t then they usually don’t want it. “I’m good, I don’t need that. I think my mom’s got it.” I think they don’t care about it as much as I do, sometimes, [laughs].

Every once in a while, you’ll meet a guy who says he had his sponsors send a box to his parents. Guys like that were thinking about it but a lot of them weren’t, they were just in the moment

Do you think the tendency to avoid riding your own product back in the day contributes to how little of it is around now?

I do, I think people would get a box and sell whatever they didn’t skate. Every once in a while, you’ll meet a guy who says he had his sponsors send a box to his parents. Guys like that were thinking about it but a lot of them weren’t, they were just in the moment and didn’t know it that it would matter so much, I think. I couldn’t imagine Gino saving boards back then, but I bet his parents did. It’s all about the moms, the moms save the decks, [laughs].

Anytime someone says they don’t have their first board I’m like, “Wow, that’s crazy.” Anyone who doesn’t save their first board just really doesn’t care, in my opinion, [laughs]. Not in a bad way, they’re just not into the physical aspect of holding onto something which is fine. Healthy.

Jason Dill, Bobshirt (2017)

When you gave Dill the Henry Sanchez Terminator board, he remarked that graphics back then were just “stealing from mainstream culture.” Obviously, that’s still rife in skateboarding but do you think it’s done less creatively now?

I do. For some reason, the rips back then were just fresher. Not like ‘fresh’ as in ‘cool’ but the idea was fresher. Now you just see a rip and think, “There’s a rip. It’s a soap company. Great. What’s the tie in?” With the Henry Sanchez board, I think they used to call him “the Terminator” and he was on a tear back then, he was a machine, so it had that tie in. It wasn’t just some Kool-Aid bite, you know what I mean? The idea of doing a rip was a little newer back then.

Now you’re this far in, how do you decide who to interview for Bobshirt and who to shoot portraits of for the Deckaid shows?

I don’t shoot all the portraits anymore; Sarah will reach out and we’ll get a lot like that because we can’t be everywhere. As far as the interviews go, I’ve definitely slowed down as I’ve flagged down a lot of the people I wanted to do. I don’t want to do them just to fill space, I just want to do them for the guys I get excited about. You know, guys aren’t in New York all the time and it’s hard to catch them. Somebody will come through and by the time I’ve heard about it they’re already leaving. “Oh, next time!” and next time might be three years from now, [laughs].

It’s easier to do the bigger guys but it’s also harder because their stories have been told so many times. That’s where the objects help … If I had to come up with real questions to ask these guys, I would tank

How important is it to you to shed some light on skateboarders who are kind of unsung, like Rodney Torres, in comparison to doing a Bobshirt interview with someone whose influence transcends generations, like Josh Kalis, for instance?

Those are my favourites. I did Jimmy Chung and I loved that one. I would do it differently now, I would do it longer and have different questions. But I like the small companies and with the small companies comes the lesser known riders, usually. I mean, Rodney rode for Rhythm, but I like to do the guys who aren’t as well known, and their story also hasn’t been told. Rodney had a big impact on New York City skateboarding, but his story wasn’t out there so much.

But, doing these interviews, getting the chance to interview Jason Dill, Josh Kalis and Brian Wenning; that’s amazing. I love doing the bigger guys but I also love doing the smaller guys just as much. It’s easier to do the bigger guys but it’s also harder because their stories have been told so many times. That’s where the objects help. I’m not that great of an interviewer so when you the bring the objects, the objects help to tell the story. You don’t have to come up with questions really. If I had to come up with real questions to ask these guys, I would tank, [laughs].

But, doing these interviews, getting the chance to interview Jason Dill, Josh Kalis and Brian Wenning; that’s amazing. I love doing the bigger guys but I also love doing the smaller guys just as much. It’s easier to do the bigger guys but it’s also harder because their stories have been told so many times. That’s where the objects help. I’m not that great of an interviewer so when you the bring the objects, the objects help to tell the story. You don’t have to come up with questions really. If I had to come up with real questions to ask these guys, I would tank, [laughs].

Speaking to Rodney at Flushing Meadows was a nice touch, I felt that amplified how passionately he spoke about the spot. Are you hoping to do more that are ‘on location’ in that regard?

Yeah, that’s always the goal. I did Jimmy and Kalis at the Municipal Building in Philly, it’s good to tie the spot into whoever you’re interviewing but it doesn’t always work out like that. Every single interview is always on the street, just on the sidewalk, and it makes it a little more casual. We try to tie a spot in, but we can’t always do that, like Jason Dill was on a roof. He was like, “I want to shoot it on the roof of my hotel,” and you’re not going to try and change that, [laughs].

How do you weigh up the idea of collecting boards because they have personal resonance against the business aspect of skateboarding which is built on marketability?

When you take a step back you’re like, “I’m collecting a brand and this brand is trying to make money,” basically. Is that what you’re saying? Because I’ve had those feelings. I mean, not from back then because I don’t think any of those brands made money. 101 and all that, none of them made money. But there is a question of, “Why am I identifying so much with a brand?” It’s a weird feeling, sometimes, but it’s more about the skateboarder and the artist. When the skateboarder and the artist come together and it clicks and it’s a nice graphic, you’re like, “That’s what skateboarding is.” You know, a sick skateboarder, a sick artist, a nice graphic and a good time period of your life.

Tim and Pops at the first Deckaid show back in 2015. photo: Jersey Dave courtesy of Deckaid

Alien Workshop, Habitat and Chocolate decks from the era you’ve collected are some of the most sought-after boards in general. But, as you said, you’re also a fan of smaller companies like American Dream. In the mid-2010s, there was a renaissance of smaller board brands which I often heard people say was reminiscent of the ‘90s. Do you feel there are parallels with the graphics from companies like Fucking Awesome, Quasi, Theories, and so on, and are you drawn to them?

I am. I loved Mother when it came out and grabbed a couple of their decks, but I don’t really buy decks from newer companies [to collect]. It’s just a different feeling for me, I buy the old boards for the nostalgic reason. I like what the newer companies are doing, and I still like small companies and gravitate towards them. Sarah got me a Quasi deck for Christmas and that’s the next thing I’m going to set up. She knows. [Laughs.]

I hate it when guys are like, “The best era is the ‘90s.” No, it’s not. Not to some kid who is 15 right now, they aren’t going to give a shit – as they shouldn’t.

You’ve previously said that you feel the time people grow up in should be the best era to them. So, can you see the same archivist spirit carrying on in the era of post-internet skateboarding culture?

I hope so. There’s less physical stuff out there these days, there’s just boards, and things come out a lot quicker, but for every era, that’s the golden era for every generation, basically. Whatever you come up in, that’s your golden era. And no era is better than the other era. I hate it when guys say, “The best era is the ‘90s.” No, it’s not. Not to some kid who is 15 right now, they aren’t going to give a shit – as they shouldn’t.

I love the ‘90s, and I love the art direction and everything people were doing because everything was so fresh and new, but companies are doing cool graphics now. Companies are so tuned in to having an image that it’s so focused now, and that’s a great thing.

When I started collecting, nobody was collecting Alien Workshop stuff and now, that’s like the stuff to get for a big group of people. I think there’s always going to be somebody out there that wants a physical piece from when they first started skating or their first board or the company they were drawn to, that they have really identified with. I hope people will always collect to preserve what skateboarding is from their era because I think it’s important to keep this stuff around, obviously.

Sarah and Tim (centre-right) with the Deckaid team at House of Vans Chicago (2019)

Get stuck into the Bobshirt interviews here and learn more about Deckaid at www.deckaid.org (a note for any of our readers in the US: the next show takes place on February 28th 2020 at AIA Gallery in Tampa, Florida).